Curious about life as a modern-day maharaja, I asked Singh, who assumed the throne as a four-year-old boy in 1952, how he was perceived in today’s India. I expected indignation, outrage, a hmmph, a roll of the eyes. But he replied with frankness and a hint of melancholy.

“In 1971 Mrs. Gandhi pulled the carpet from under our feet, and our privileges were gone. This palace was built for entertaining, but now it’s beyond us. Many people today look at me and think, ‘Who the hell are you, who are all these people, the maharajas with all this land?’ The young people though, they are much more inquisitive because they didn’t grow up in those times. They want to learn about the British and the Raj.”

I took a tour of the palace, a stupendous pile of local sandstone that took 15 years to build; it was completed in 1944, three years before Indian independence. Who couldn’t entertain here? The Trophy Room had tiger, deer, and buffalo heads mounted on the walls. An ornate rotunda loomed above a colonnaded lobby. Not a leaf or blade were out of place in the pretty, symmetrical interior courtyards or sprawling, manicured gardens. The basement pool, ringed by tiles representing signs of the zodiac and now the centerpiece of the spa, was originally reserved for royal ladies. And in a measure that embodied the ubiquitous richesse, the urinals in the main-floor men’s bathroom were always filled with ice cubes.

The pristine Umaid bhawan contrasts to the faded glory of Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur’s prime attraction and the former home of 17 generations of the maharaja’s clan. Begun in the 1400s by Rao Jodha, the city’s founder, the majority of the fort dates from the mid-17th century; today, it serves as a museum.

Built of red sandstone, Mehrangarh is a hugely impressive citadel, commanding a rocky outcrop more than 100 meters above the rest of the town. I wandered around its courtyards and chambers and halls, inspecting ceilings of mirror and gilt, a room filled with swank baby cribs and strollers, and gleaming scalloped doorways that framed stained-glass windows. There’s also an armory filled with terrifyingly shaped swords and daggers with virile names like talwar, khanda, sosun pattah, shamshir, pesh-kabz, khanjar, chillanku, bucchu, jambiya, and katar, each one described in detail.

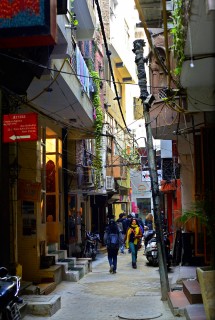

As I reached the highest floor I turned onto a narrow balcony and saw the same vision of the city that I’d first seen as a young boy, when my parents took my sisters and me on a tour around Rajasthan, their home state. Spread out before me was a sea of squat blue houses, as if some deity had dropped a giant dollop of paint onto the arid plains below. The houses’ characteristic color originally identified them as the homes of Brahmins, the priestly/scholarly caste at the top of Hinduism’s pecking order. That distinction is now a thing of the past, though Jodhpur’s nickname of the Blue City endures.

With the sight still lingering in my mind, I returned to the Umaid Bhawan to attend a Royal Salute whisky tasting hosted by Chivas’s brand director, Neil Macdonald, a Scotsman with an easy smile. In his preamble, he talked about Royal Salute’s heritage—it was launched in 1953 to mark the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II—and how each whisky was aged in oak casks for a minimum of 21 years. The first sip was sharp—it was only 1 p.m. after all —but after adding a dash of water, the layers of the blend revealed themselves. With the soothing voice of a guru, Macdonald spoke of top notes like honey, baked peat, autumn leaves, banana, plum. I, inexplicably, detected coffee and licorice. “The great thing about whisky is that there’s one out there for everyone, even people that don’t drink it. They just don’t know it yet,” Macdonald said.