A land layered with ancient civilizations and dramatic scenery, Greece’s largest island is also home to one of the world’s healthiest (and tastiest) cuisines. Add to that a burgeoning wine industry, and you have all the ingredients you need for an unforgettable Mediterranean sojourn

By Sanjay Surana

Photographs by Jannik Weylandt

Clichéd as it may sound, I had pictured my first meal in Crete to be at a taverna, bellied up to a hefty wooden table in a cobblestone courtyard under the shade of a carob tree. But my ferry from Santorini was criminally delayed, and by the time I checked in to the Blue Palace, a waterfront resort in northeastern Crete whose name is both deceptive and accurate (it’s not blue, but it is palatial, with haunting views of the Venetian-built island fortress of Spinalonga), it was nearing midnight. Starving but in no mood for room service, I strolled over to the neighboring village of Plaka and into Delphini, a harbor-side restaurant where bouzouki music was blaring, but the tables were empty. A bearded young man in a sweatshirt materialized from the kitchen.

“Kalispera,” he beamed, bidding me a good evening.

“Are you open?”

“Yes. Kitchen closed. No cooked food. But you can take out.”

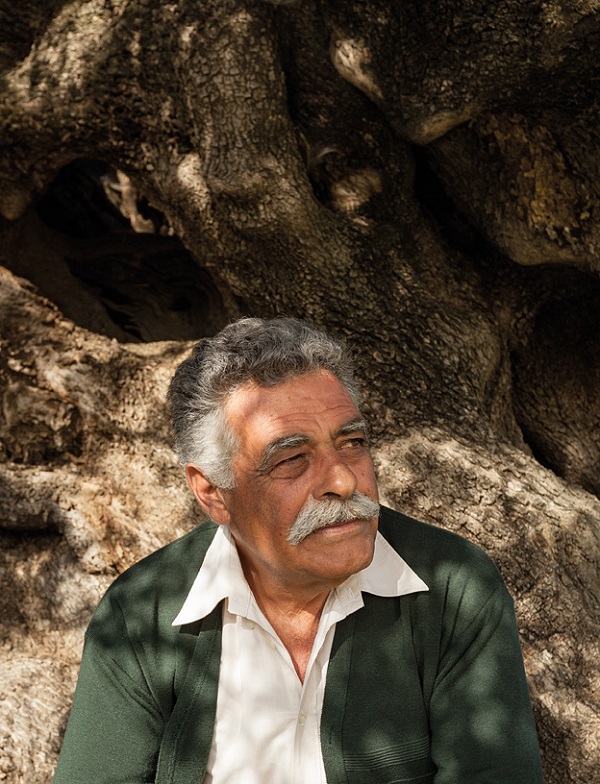

While waiting for my order—horiatiki (Greek salad) and fava (a puree of yellow beans doused in olive oil)—we chatted about Cretan cuisine, which is what had brought me to this southern Greek island. Before long I knew his name, Kostas Mathaiakis; that his family owned both this restaurant and the nearby farm that supplied its vegetables, olives, and olive oil; and that his zucchini croquettes were, his words, “the best on the island.” My food arrived, and as I prepared to leave, he took me by the wrist, led me into the kitchen, opened a steel locker, and scooped out a handful of miniscule tomatoes and a long, misshapen cucumber the color of a young lime. “Here, please take these,” Mathaiakis implored. “They are from my farm. Fresh. I picked them today. Take, take.” How could I refuse?

Back in my room at the Blue Palace, I opened the foil packs, fully prepared to be unimpressed. Shame on me. Mathaiakis’s fava was a revelation, fluffy as whipped butter, each mouthful hinting of hazelnut. And his oregano-dusted salad was fresher and more flavorful than any I had eaten since arriving in Greece 10 days earlier, with chunks of creamy feta imparting an unexpected tang.

After rushing the meal in the way the famished do, I popped the tomatoes into my mouth. With each tiny explosion of flavor I tasted acid, sweetness, grass, earth; they were the finest tomatoes I’d ever ingested. And the cucumber, despite its malformed appearance, had none of the bitterness or sponginess of commercially grown cukes. If takeout from the first place I had wandered into was this good, what else could I expect to eat in Crete?

The world is no stranger to the nutritional richesse of Greece’s largest island thanks to health studies conducted here in the mid-20th century. In 1948, the Greek government invited researchers from New York’s Rockefeller Foundation to investigate ways to improve the postwar living standards of its southernmost citizens. Led by epidemiologist Leland Allbaugh, they found that the Cretan diet, despite being meager in meat and high in fat (mostly from olive oil) and wine, was in fact an extraordinarily healthy one, as evinced by a confoundingly low incidence of heart disease. University of Minnesota physiologist Ansel Keys encountered similar results with his Seven Countries Study, a groundbreaking health survey begun in 1958 that examined the relationship between food intake and cardiovascular disease in the United States, northern Europe, and southern Europe. The results from the test group on Crete were consistent with those of the Rockefeller Foundation, and the dietary patterns typical of the island in the 1960s —focused on fresh ingredients such as olive oil, fruits, and seasonal greens—became the epitome of the so-called Mediterranean diet.

“The diet here has been one of poor people who ate what was on their land. It just happened that the food was very healthy,” Elena Parvantes, an Athens-based nutritionist, told me. “There are hundreds of wild greens, or horta, that are nutritious and rich in antioxidants and Omega-3 fatty acids. Olive oil is loaded with monounsaturated fat but low in calories; snails are full of protein. And rare for an island, Crete is self-sufficient in food. It’s like the California of Greece, it’s so fertile.”

The attraction of Cretan food lies in its simplicity. Unlike the sauce-laden cuisine of the French or the complexities of Indian cooking, dishes here are pulled together with minimal preparation, presenting ingredients on the plate as close to their natural state as possible. That’s not surprising. Spend enough time in Crete, and it’s evident that nature remains in control. On any road, be it the highway that connects Heraklion to the east or a narrow roadway snaking into the island’s interior, the oleander bushes and fir, pine, cypress, and eucalyptus trees close in on the pavement, slowly creeping forward to reclaim what was once theirs. Though most Cretans live along the coast, the island’s pulsing heart is its mountainous, sparsely developed interior. For Cretans living away from the shore, the grip of modernity firmly takes second place to the traditional, nature-governed ways.