Above: ‘Snowy’ on a stretch of road in West Bengal.

A trailblazing truck tour from Nepal to Bhutan aims to bring a measure of luxury to the high roads of the Himalayas

By Jason Overdorf

Photographs by Jyothy Karat

Eighty kilometers from the Bhutanese border, near the West Bengal town of Chalsa, the landscape flattens and expands. From the mist-shrouded Himalayan foothills of Gorkhaland, the terrain spills into wide, green rice paddies, scattered plantations of Assamese tea, and forests of mango trees drooping with fruit. It is beautiful country, beautiful enough to make you want to linger forever. But Snowy, our custom-built Mercedes-Benz truck, was charging through it hard. The first commercial overlanding expedition to enter Bhutan, we had an appointment to keep with border officials at 1:30 p.m. Nick Fulford, our driver, was worried that we might not make it. Naturally, we blew a tire.

“Must have scraped the sidewall on one of those potholes,” Nick grumbled, pulling over in front of a school.

A onetime farmer from Essex, England, Nick has seen his share of punctures. He’s been driving truckloads of adventurers through Asia, Europe, South America, Africa, and the Middle East for the better part of a decade. He can spin a tractor-trailer on a dime and thread it through the eye of a needle. He can also tell a good tale, and knows everything there is to know about the road. “Ever driven in the Punjab?” he asks laconically. “Around here, cyclists get off the road when you honk. But in the Punjab, they’re Sikhs, right? They’re too proud. You have to watch out, because they don’t give way.”

I was riding shotgun in the truck’s high cab when the tire blew, so I climbed down after Nick and joined the rest of the crew—Bangalore-based photographer Jyothy Karat and veteran British travelers Steve and Janet Edwards—on the asphalt outside the school gates. Janet’s flaming red hair and Steve’s silvery beard and ponytail had already attracted the attention of the local schoolboys, who, dazzled by the prospect of seeing this unlikely group of foreigners change a tire, settled in to watch our antics like it was the final episode of Lost. When we eventually reboarded, soaked in sweat and grease, I’d learned that the lug nuts on an eight-ton truck get hot enough to burn the skin off your fingers. I’d also learned that school classes in Chalsa run on IST: Indian Stretchable Time. But the pothole that set us back turned out to be the last, and the road stretched out smooth and unbroken before us. Despite stopping to check directions at every crossroads, we rolled into the Indian border town of Jaigaon at just about two o’clock —the nearest Snowy had come to hitting a deadline in four days. An hour later, having been ushered through customs by a Bhutanese guide named Bhupendra Chettri, we were drinking celebratory beers in the lobby of Phuentsholing’s Lhaki Hotel—the first overlanders to bring a big rig across the border.

This pioneering “Two Kingdoms” tour through Nepal, India, and Bhutan was perhaps the most ambitious of the dozen or so itineraries developed by Australian truck driver–turned-entrepreneur Ben Grayling for Best of Asia Overland (BOA), his Kathmandu-based company. Derived from an Australian stockmen’s term for cattle drives, “overlanding” relies on heavy trucks and off-road vehicles for marathon trips across the sort of terrain that most travelers never get the chance to see. Commercial overlanding began in the 1960s, largely in Africa, offering once-in-a-lifetime adventures where the goal was less the destination than the journey itself. Often grueling, such trips quickly attracted a young, cult following, but never really evolved beyond their rough-and-ready roots. Today, there are maybe 30 overlanding outfits worldwide, the largest of which, Britain’s Dragoman, has a fleet of 25 trucks operating primarily in Africa and South America. Guests can expect to pitch their own tents, cook food, clean dishes, and do whatever jobs are needed to keep the truck rolling, like digging it out of the sand—great when you’re 25, but less so when you’re 55.

By designing smaller, more comfortable boutique journeys based around hotel stays rather than camping, Grayling is hoping to reinvent overlanding for a more mature (or at least leisure-minded) clientele. “We’re basically trying to create a new market,” says 43-year-old Grayling, who worked seven years as a driver and expedition leader for Dragoman before starting BOA in 2008. “With our trucks, we can get off the route, we can stop and start where we like, it’s not like a coach tour. But when it comes to the tougher, hands- on aspects of traditional overlanding, I’m trying to steer clear of that.”

To that end, Snowy, the first of BOA’s refitted trucks, is equipped with room for just 14 passengers, giving its interior the spacious, sociable feel of an American RV rather than a tour bus. There’s a powerful air-conditioning system, a wet bar, and a refrigerator. The seats are comfy and adjustable. And once fully operational, Snowy will offer Wi-Fi by tapping into local GPRS networks along the way.

The excursion we had joined—Kathmandu to Kolkata via Bhutan—was an exploratory trip (albeit one with paying customers) to test Grayling’s business model on a road that is quite literally less traveled. Only opened to tourism in the 1970s, Bhutan remains one of Asia’s most exotic and least-visited destinations. There’s no railway, so the only way to see the country is by road. Although the government no longer imposes a limit on the number of visas it issues to travelers, tourist arrivals still number only around 25,000 a year due to the constraints of the country’s single-runway international airport, which is serviced by just a handful of Druk Air flights from Kathmandu, Bangkok, and various Indian cities. The erstwhile king’s commitment to expanding “gross national happiness” (as opposed to gross national product) has succeeded in protecting the country’s natural beauty and cultural heritage. But if our foray into Bhutan proved anything, it was that overlanding will always be overlanding: best enjoyed by travelers for whom the journey—and not the plush lodgings at the end of it—is the ultimate goal.

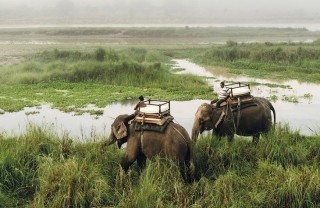

For the Edwards—fiftysomething adventurers smack in the sweet spot of BOA’s target market—a flat tire was a lark. By the time Jyothy and I joined them mid-journey in Siliguri, West Bengal, Janet and Steve had endured an ordinary traveler’s nightmare of missed connections and eleventh-hour itinerary changes. They were originally slated to begin their 18-day journey in Kathmandu, passing through Nepal’s Chitwan National Park en route to Bhutan. Instead, on their first go, they’d flown from Delhi to Kathmandu only to have their plane turned back because of bad weather. Two days later, they returned to Kathmandu, just in time for a countrywide general strike that stopped all road traffic, bicycles included. Nothing was moving, especially not Snowy: the truck was still stranded in India. The new plan was for the Edwards to fly to Varanasi, meet Nick there, and drive into West Bengal via the Buddhist pilgrimage site of Bodh Gaya, in the neighboring Indian state of Bihar. Then that flight was canceled. Janet and Steve flew back to Delhi, spent another night there, and finally reached Varanasi a full five days into their holiday—which meant they’d need to blast through the 16 hours to Siliguri in one go to get back on schedule. They did it without a whimper. They had fun.

“For us, getting to see India’s holiest city [Varanasi] was a bonus,” Steve told me later.

“If you don’t actually enjoy the drive,” Janet added, “then you shouldn’t be doing it. Fly. But by driving, you get to see places you wouldn’t otherwise see. You just have to be adaptable. If one day you’ve got to do 16 hours on the road, you do 16 hours.”

To be honest, for the first two or three days of my comparatively smooth trip, as we traveled through the tea estates of Darjeeling and to Gangtok, capital of Sikkim, I wasn’t entirely convinced. Having worked as a reporter in India for eight years, I’ve seen my share of monsoon-battered blacktop—most of it spent white-knuckled in the back of a kamikaze-driven Ambassador taxi. But after a while, the rhythm of truck travel got to me. My old wanderlust flared up again, and the days on the road stretching out ahead of us began to look like what they were—not an obstacle to be overcome, but a welcome escape from everyday life. Instead of longing to stop, I started dreaming that we might keep going, and that the real world might never catch up to us.

Then we hit Bhutan.

If there is any place left that can take you out of your head and make you forget about the grinding plod of work back home, this is it. With its strange, myth-steeped history and curious blend of Himalayan grandeur and lush forest, Bhutan tempts the outsider with a romantic fantasy of a mountain-fortified paradise made all the more alluring by the difficulties of getting there. Former king Jigme Singye Wangchuck’s famous plan for modernizing the country without sacrificing its environment or culture means that there is not a single neon sign or concrete monstrosity. There were no tourists here until 1974, no television or Internet until 1999. Though wild marijuana is ubiquitous, locals use it to fatten their pigs, and consider dope smokers to be on the same level. Until the king abdicated the throne and established democracy in 2008, a theocratic monarchy based in Tantric Buddhism governed the country for centuries, so fortified monastery complexes called dzongs—festooned with startlingly lifelike phalluses to ward off evil—preside over every emerald-green valley.

Above from left: A hilltop monastery near the old Bhutanese capital of Punakha; precipitous parking; on the road to Thimpu; a vendor at Bhutan’s Dochula Pass.

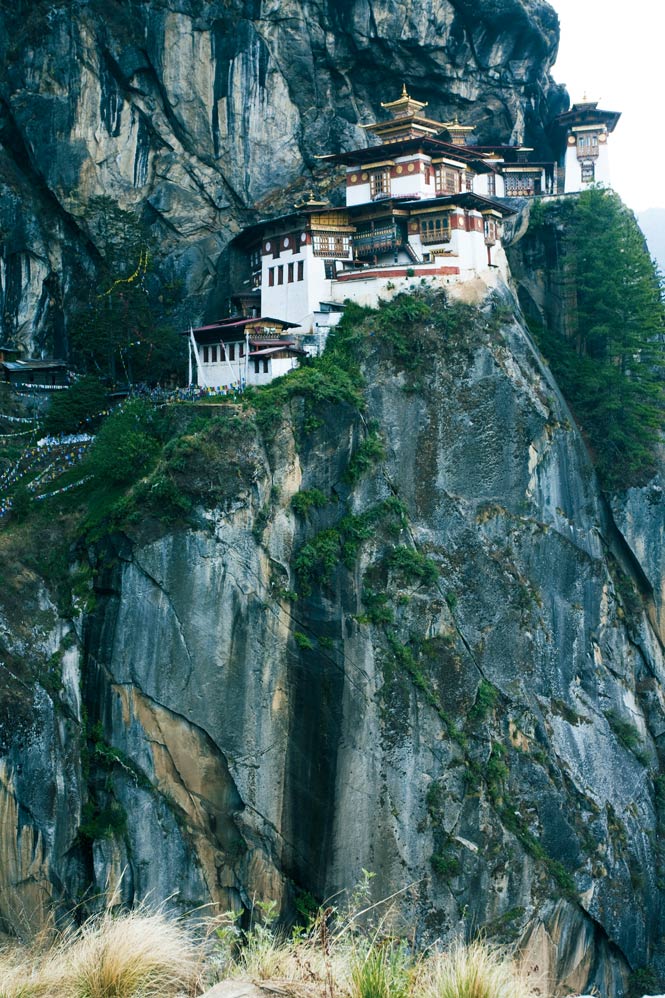

Bhutan is only about the size of Switzerland, but roads are tortuous and few and far between. Most travelers, therefore, visit only the three central valleys that best highlight Bhutanese culture: Paro, home to the country’s sole airport and the Tiger’s Nest monastery, its most famous historical site; Punakha, the old capital; and Thimphu, the present seat of government where the green shoots of modern life—mobile phones, gelled hair, nightclubs—are most evident. As overlanders, we were able to see all that and more.

From Phuentsholing on the Indian border, we abruptly climbed to 900 meters above sea level along a series of steep switchbacks. Every bend unveiled a view of thickly forested mountainsides and terraced farmland. Maintained by India’s Border Roads Organisation in exchange for rights to hydroelectric power, the two-lane highway was smooth and unbroken. Still, it was hard going for Nick; even with the relatively sparse traffic, hauling Snowy around hairpin turns was like a tightrope act.

Seated in back, I followed our progress on a map I’d picked up in Gangtok, as Bhupen, the guide who had joined us at the border, calculated and recalculated our arrival time. It didn’t help that the pre-monsoon rains of late spring had washed out the road at one point, obliging us to wait for an hour as oncoming trucks and jeeps streamed past.

Finally given the right of way, Nick revved the engine and Snowy half-swum through a mess of gray slurry. Alongside us, whole families of Indian road workers cleared debris. Here and there a grandmother sat cross-legged on a cliff edge, an umbrella spiked into the ground beside her to shield a wriggling infant, while mom and dad lay fieldstones and slathered mortar to shore up the embankment.

A couple of hours later, traffic was stopped again, as another road crew worked to clear some fallen rocks. When we resumed our climb, Nick had to brake to let another set of boulders skitter and bounce across the road ahead of us. Bhupen leaped up and pounded on the side of the cab, shouting, “Go, go, go! Don’t stop, man,” and Snowy roared up the mountain. “When a few of them come down, that means more are coming,” Bhupen explained, clearly rattled.

As we made our way through the valleys and over the remaining passes, Bhutan’s charms began to assert themselves. Wreathed in mist, the roadside was dotted with tiny monasteries, whitewashed farmhouses, and imposing dzongs. Though today the traditional dress code is not rigorously enforced, most of the men and women we passed wore gho and kira, as the bulky Bhutanese robes are called. And I didn’t see a single TV antenna or satellite dish, though Bhupen assured me that locals are addicted to Indian soap operas.

Later, as the sun was setting, we got our first lesson in gross national happiness when Jyothy asked about what appeared to be a majestic white dzong nestled in the mountains high above the road. “It’s a prison,” Bhupen said with a twinkle in his eye. “The criminals who are serving life sentences have to stay there, but they are allowed to marry the local women.” That’s as close as I got to the place, so I couldn’t swear it won’t ever earn a spot on Locked Up Abroad. But from a couple of kilometers away, it almost made me want to rob a bank, just in order to get incarcerated there. An hour later, we saw the lights of Thimphu. We’d left Phuentsholing around 9:30 a.m., and put in a typical 10-hour day on the road. But all of us were exhilarated.

The next four days were perfect, or would have been if they had each been 48 hours long. In Thimphu, we trailed a bunch of guys in ghos and Nikes to the archery grounds to watch Bhutan’s national sport, toured the local monastery, and stopped in at a surprisingly good museum dedicated to rural culture. But I also managed to find a bar called Benez where expats and aid workers hung out, and after taking advantage of the Red Panda weissbier on tap, I inadvertently wandered into a local nightclub. By midnight, the place was packed with Bhutan’s twentysomething swish set, and the picture of a tranquil Himalayan kingdom fighting off the influence of the outside world exploded in my face as girls in bandage skirts and guys with spiky hairdos shouted into phones, downed vodka Red Bulls, and gyrated to Lady Gaga.

In Punakha the next day, Jyothy and I headed off at 4 a.m. to catch the sunrise over Punakha Dzong, where the jacarandas were blooming at the confluence of the Pho and Mo rivers, before joining the Edwards for a tour of the 17th-century fortress. We all woke up early in Paro as well, for a climb to the famed Tiger’s Nest, set 900 meters up a cliff face. This also yielded an unexpected luxury. At 8 a.m., when they unlocked the monastery gates, the five of us were alone with the monk and sentry at the top, looking over the valley. Only when we were halfway down again, and began meeting people trekking up, did we realize that the place is usually packed with tourists.

Discounting unpredictable delays due to strikes, landslides, and tire punctures, the slow pace of truck travel has its benefits. You absorb more of the scenery when it’s not flashing by, for one; for another, you’re forced to abandon the “get there faster” attitude of deadline-obsessed modern life. Even so, the logistics of the trip put us on a cruel timetable in Bhutan. To get from Punakha to Paro, for example—a scant 50 kilometers as the crow flies—involved a five-hour drive along a winding highway. That meant that the only “day” I spent in a beautiful rustic cottage at Punakha’s Kyichu Resort began after dark and ended when I left to watch the sun rise over Punakha Dzong, before I’d even had the chance to admire the babbling stream beneath my balcony in the sunlight. (I’ve since learned that BOA, which plans to upgrade this trip from “mid-range” to “luxury” for next year’s season, is mulling the addition of another day or two to the Bhutan portion of the itinerary. Given all that there is to see there, they’ve got my vote.)

Nevertheless, as we charged down to Phuentsholing and crossed the border into India again, beginning the uneventful, 700-kilometer slog for Kolkata and our journey’s end, I reflected on the fact that the advantages of BOA’s “boutique overlanding” more than compensated for any drawbacks. Snowy carries a maximum of 14 passengers in the space that a coach tour would put 30, leaving plenty of room to spread out and generally make yourself at home. And at every town we visited—at every border crossing and rest stop—the truck’s captivating white bulk was greeted as a spectacle on the order of Ken Kesey’s magic bus, Furthur. In Thimphu, even the young leader of the two-person parliamentary opposition had felt compelled to climb aboard for a look.

Best of all, though, was that I never for a second felt like cargo. When we finally rolled into the bustle of Kolkata, 10 days after Jyothy and I had joined the trip in Siliguri, I was in the cab navigating. Or rather, I was hanging out the window to see if we had enough clearance under a railway bridge. We didn’t, so I jumped down to direct traffic as Nick executed an improbably graceful three-point turn. That’s when I remembered what BOA’s Ben Grayling had told me over the phone about his first-ever overlanding adventure, from Nairobi to Cape Town in 2000. “I did that trip. It was a ripper,” he had said. “Then I thought, ‘I reckon I could do this job.’”

So could I. If only I could drive a truck.

To learn more about Best of Asia Overland’s truck excursions in South Asia, visit boa-overland.com or call 977/984-165-2591. The 18-day “Two Kingdoms” tour described in this story is currently priced at US$3,210 per person, including meals, accommodation, and activities.

Originally appeared in the August/September 2010 print issue

of DestinAsian magazine (“Driven to Distraction”)