The splendid colonial-era architecture in Yangon, the city’s treasure, is mildewing and crumbling, with ferns and shrubs sprouting on Neoclassical cornices—all very romantic, but symptomatic of a dysfunctional economy that has left the country’s 55 million people in poverty. Spare parts for airplanes are not to be had, which makes maintaining a domestic air network almost impossible. On a trip to the country in 2004, I was stranded in a northern airport for eight days, waiting for my return flight to Yangon to materialize.

Yet while the “fundamentals,” as a stock analyst might put it, remain unaltered, it wouldn’t be quite accurate to say that nothing has changed. Myanmar is doing everything in its power to look different. Yangon’s handsome new international airport makes arriving there much faster and more welcoming than in the past, when irritable soldiers searched passengers’ bags down to the last sock. Now the young woman at passport control looks you in the eye and smiles when you present your documents.

On my previous visits, the first landmark to greet me as I approached the city was a long vermilion sign proclaiming THE PEOPLE’S DESIRE, a menu of slogans such as “Oppose those relying on external elements, acting as stooges, holding negative views,” and “Oppose foreign nationals interfering in internal affairs of the State.” The sign exerted the fascination of an artifact from an alien land, but it didn’t exactly make you feel welcome. On my latest trip it was gone, replaced by a billboard advertising an exhibition of jade jewelry.

My taxi brought me to the Strand Hotel, one of the grande dames of Asia. It was opened by the Sarkies brothers (founders of the Raffles in Singapore) on the banks of the Irrawaddy River in 1901, when the city was known as Rangoon. By the end of the 20th century, the hotel had fallen into an advanced state of government-run dilapidation, and was taken over and tastefully restored by renowned Indonesian hotelier Adrian Zecha. I dropped my bags in the room and checked my e-mail using the hotel’s Wi-Fi, then slipped into the street to join the flow of humanity, as a blood-orange sun sank into a silvery mist.

Yangon is one of those cities that, if you ever once get to know it, remains forever in your memory. Its downtown, laid out in a spacious grid of streets by British military engineers, is instantly navigable on foot in the way that New York City is. Merchant Road, the main east-west axis, swarmed with people selling and buying, eating and drinking, or simply giving themselves an airing at day’s end, as I was. (Another instance of no change being good: Yangon’s streets never have traffic jams like other major cities in the region.)

The magnificent haute-Edwardian High Court building, painted rose with lemon-yellow details, would look quite at home in South Kensington; the Telegraph Office on the corner, its brass nameplate twinkling, defies change by peddling its anachronistic technology.

Behind the High Court, Maha Bandula Park was in brilliant bloom. As ever, the fortune-tellers were open for business on the sidewalk by the park’s entrance. I stopped to have my palm read by a canny middle-aged man wearing a dark green longyi. The session began, as usual, with a bit of small talk: Where you from? U.S.A.? America number one, Obama very good man! Then he took my hand and after studying it intently, predicted that I would travel to faraway lands. Amazing! How did he know? My first wife would be very, very beautiful but die young, he said; my second wife would be a “big-money lady.” He told me my lucky number and I gave him one American dollar, still the preferred currency in Myanmar. His face lit up with a satisfied smile.

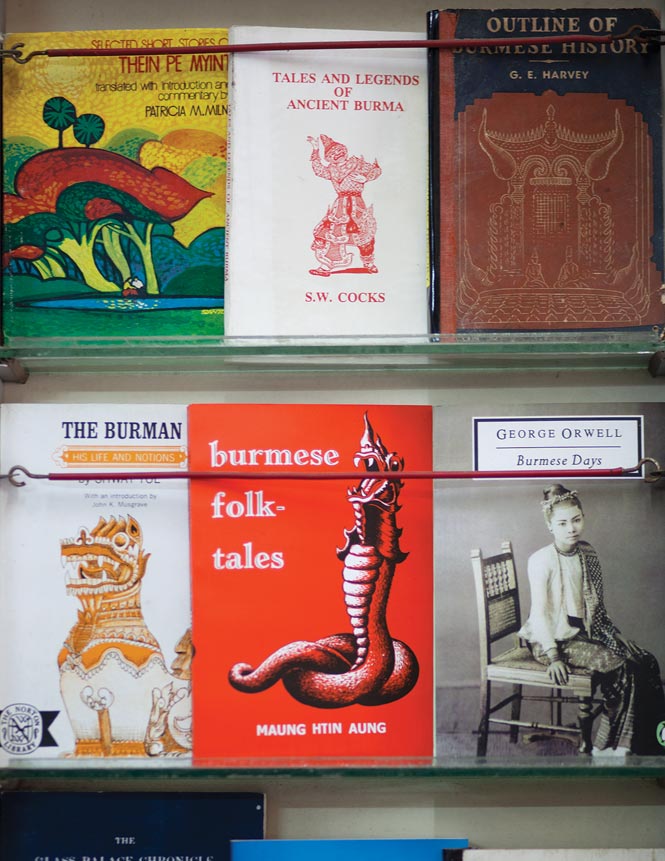

North of the park, the Sule Pagoda gleamed in liquid gold; beyond it, City Hall, an Art Deco pile from the 1920s, painted pale lavender since my last visit, loomed like a barbarian citadel out of some fantasy comic book. I turned back toward the river and confidently found my way to the Bagan Book House, a Yangon landmark founded by U Ba Kyi, something of an institution himself. On all my previous visits, the old man had held court amid dim, tottering piles of yellowing paperbacks, dog-eared textbooks, and bound photocopies of Western classics. Yet, as I feared, he had died since my last trip. His son has taken over the shop and made it much brighter and tidier than it ever was in his father’s time. He invited me to join him for a cup of tea—the Burmese are even more fanatical about the stuff than the British or the Chinese—and we reminisced about old times, as U Ba Kyi’s toddling grandson clung to my pants and stared at me in drooling wonderment. Then we talked about conditions in his country today, but I can’t tell you what he said.

When change does come here, it usually generates more controversy than improvement. The country’s name, for starters: this magazine prefers Myanmar, its official designation, over the traditional Burma. The change was instituted in 1989 by the military junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), soon after it seized power. The United Nations and ASEAN use the new name, as do some prominent American news organizations, including the New York Times and CNN. Most Western governments side with Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy by retaining Burma, as do other major international news organizations, such as the BBC and the Washington Post. There is no right answer.

Another point of dispute is whether or not foreigners ought to go there at all. As a part of the trade sanctions, some human-rights groups have, until recently, urged foreign tourists to boycott the country. The mainstay of this position was the Burma Campaign, supported by Hollywood celebrities such as Jennifer Aniston and Jim Carrey. On the other hand, the Free Burma Coalition, whose members are exiled Burmese dissidents, actively support foreign travel in the country, in much the same way the Dalai Lama does for Tibet. In 2010, the National League for Democracy dropped its support of the tourism boycott, which turned the tide; now the Burma Campaign and other organizations limit their recommendation to a boycott of package tours, which bring in revenue to the government.