To me, it was always a no-brainer: travel anywhere is a fine idea—North Korea has been at the top of my list for years—and you should avoid all package tours regardless of who’s making a profit from them. Nothing fosters tyranny more than isolation, which reinforces with iron the sense of the futility of opposition. The regime’s attempts to improve its image have resulted in some tangible improvements. Suu Kyi’s house arrest ended in 2010, and in July 2011 she made a trium-phant public appearance in Bagan, an ancient city of temples in central Myanmar, where she was greeted by ecstatic crowds. Since then, the government, now led by its first new president in 20 years, has pledged to release thousands of convicts under a general amnesty, including the more than 100 political prisoners freed in October. No one can say whether any of this signals a genuine move toward liberalization, but events of the last year have at least shed a bright ray of hope on a place that sorely needed it.

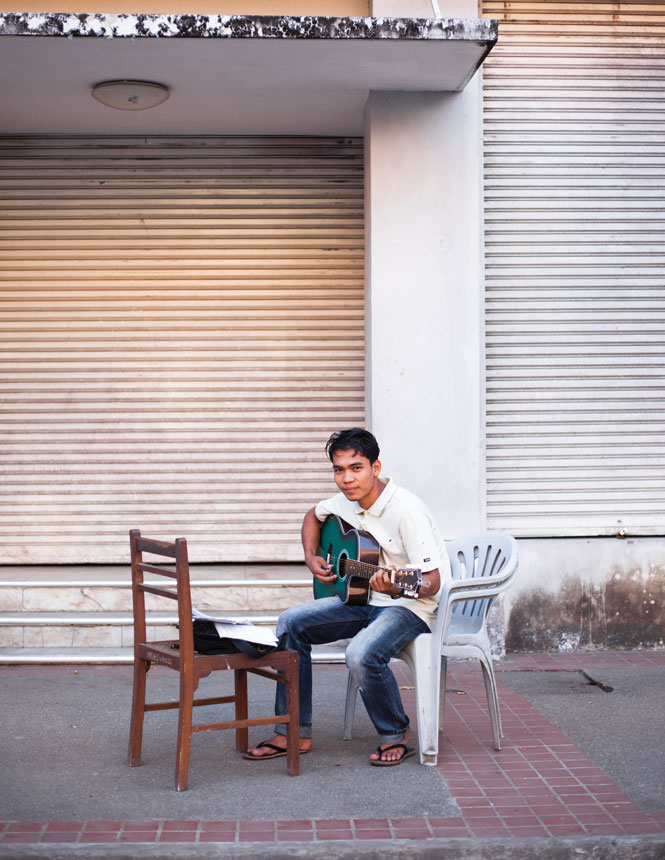

The dilemma inherent in any responsible discussion about Myanmar is that it must address the nation’s woeful political situation, which inevitably conveys the impression that it’s a depressing place to visit. In fact, it’s one of the most beautiful and fascinating countries in Asia, and extends a friendly welcome to travelers that is remarkable even in a region renowned for its warm hospitality. And the best place to experience it may well be Yangon. The pro-boycott lobby makes a good point: it’s difficult to travel in the Burmese countryside except on government-sponsored tours, which tightly limit access to scrubbed-up show villages and deny one informal interactions with ordinary folks. Yet, in Yangon, the city lives on the streets, in its markets and parks, which throb with vigorous, unhindered vitality.

In the golden age of world travel, before long-haul flights and package tours, Rangoon was a major stop on the grand tour of the Far East. The Shwedagon was a “must” on every itinerary, on a par with the Taj Mahal or Angkor Wat. I visited the great stupa on my first morning in the city. The US$5 entrance fee for foreigners includes an elevator ride to the upper level, but I decided to ascend the staircase on the monument’s southern face with the mob. Shops line the steps, selling in-cense, flowers, religious books, gaudy devotional souvenirs, and plastic golden Buddhas in every size, many with aureoles that twinkle in bright, ever-changing colors. The press of humanity and the festive atmosphere made me feel as though I was on my way to a pop concert or championship football match rather than to a religious shrine.

I entered the plaza surrounding the Shwedagon and looked up. More than the country’s symbol, the Shwedagon is the repository of the national soul. The bell-shaped stupa was constructed in the 10th century to house eight hairs from the head of Gautama Buddha. Rising to almost 100 meters from its base on the top of a steep hill, the Shwedagon soars over the approaching visitor to a height equivalent to that of the Pyramid of Cheops. For centuries, pilgrims have plated the surface of the stupa with gold leaf, which is now estimated to weigh something like 50,000 kilograms. The ornamental crown, the hti, set with thousands of rubies, diamonds, sapphires, and topazes, can be seen glittering from miles away.

The Shwedagon is old, but the city is not. To a large extent, Yangon was a British creation. The Raj built Rangoon, the administrative capital of colonial Burma, on the site of the village of Dagon, at the base of the stupa; after independence in 1948, the city became the first national capital. In 2005, the military regime built a new capital in a place called Naypyidaw, 320 kilometers north of Yangon. However, the foreign embassies are still concentrated in a quiet, verdant neighborhood northwest of Yangon’s central business district, where they occupy palatial Edwardian-era residences. A few days into my visit I moved to a hotel in the diplomatic quarter, a cluster of gingerbread-encrusted bungalows sited around a tropical garden called the Governor’s Residence (because that’s what it was in colonial times). Managed by Orient-Express, it offers a tranquil base for exploring this part of the city.

The wide lawns and impressive houses, shimmering with light and buzzing with heat, reminded me of the posh urban villages of Los Angeles. Across the street from the Governor’s Residence, the embassy of Laos occupies a Tudor-style mansion with fake half-timbering and mullioned windows, and a tennis court on the front lawn. On the corner, the turrets and galleries of India House, the Indian ambassador’s mammoth Neoclassical residence, gleamed blinding white; next door to it, another faux-Tudor house was collapsing into a spooky wreck.

A few blocks along, across the street from the Malaysian embassy, I saw another ruined house being systematically deconstructed by a work crew lorded over by a guard toting a machine gun. He returned my smile as I walked up the drive to have a look. The owner of the house came out to greet me. He said his name was Zwe Ko Ko Myint, and that he was a building contractor who had bought the house, but not the land. “I love this house. I bought it as soon as I saw it, before I had a place to rebuild it. Please come inside.” The exterior was a mess, but the interior was a lavishly finished neo-Gothic fantasy, with arched Moorish doorways, massive teak staircases, and bay windows. Myint had paid US$24,000 for the building and estimated it would cost four times that to resurrect it on a plot of land outside the city center. “Now that I have a good house,” he said, “I must get married.”

My walking tour had made me hungry, so I ended it at Padonmar, a restaurant recommended by locals as one of the city’s best bets for Burmese food. Like all the businesses in the area, it’s located in a renovated house, with caged owls in the porte cochere observing the human comings and goings. Although Burmese cuisine has never enjoyed a global vogue like Thai or Vietnamese cookery, it has a uniquely vivid palette of flavors, favoring finesse over chili fire. Boo thee kyaw, battered, deep-fried fingers of gourd served with a garlicky tamarind dipping sauce, made an addictive hors d’oeuvre, and was followed by a thoke salad of raw vegetables marinated in kaffir lime juice and flavored with ground peanuts and sesame seeds. I chose a thoke of thin-sliced green tomatoes, which I gobbled down as politely as my appetite permitted.