Above: Close encounters at Xian’s terra-cotta warriors museum.

There’s more to China’s onetime capital than the usual tourist sites

By Victor Paul Borg

What impressed me most about my recent visit to Xian wasn’t the famed terra-cotta warriors or the hulking battlements of the old city walls, though those are both remarkable. No, what captivated my imagination for the better part of an evening was a house—or, to be more precise, a 400-year-old estate called the Gao Fu.

Owned by a wealthy philanthropist named Shuanglin Yang, the Gao Fu provides a window onto the city’s history the way no army of clay soldiers can. It’s situated off Muslim Street, a cacophonous, tout-filled precinct established by Silk Road traders in centuries past. And yet, within the Gao Fu’s maze of courtyards and cloister-like corridors, all is hushed —and maybe even a little spooky. I could almost sense the ghosts of Ming-era courtiers around me.

Yang shrugged when I told him this over tea in his studio, just one of the property’s 86 rooms. After explaining how the house originally belonged to a 17th-century mandarin named Gao Yue Song, who surrounded himself with a coterie of eminent thinkers and artists, Yang talked about the four years and US$7 million that were spent on restoring this rare specimen of classic Xian architecture, now a private museum. Judging from the results—a fantasy of rich carvings, period furnishings, moon gates, and authentically re-created rooms bearing names like “men’s reception,” “women’s reception,” and “introspection room” (where unruly boys were once punished)—it has been money well spent. But it’s not money that Yang expects to see again.

“I didn’t want to turn this house into a restaurant or a hotel, and I don’t measure success by the number of tourists,” he said. “Commercialization has destroyed too many historic buildings. I want to protect this treasure as it was. It’s running at a loss, but that’s fine with me.”

While the Gao Fu is a relic of Xian’s storied past, it also represents a new direction for conservation efforts in the city. Yang is no lone sentimentalist. In 2005, the local government launched the Royal City Restoration Plan, a magisterially named heritage program that aims to restore old sites, expand tourist attractions, and encourage a rebirth of the artistic expression Xian was once famous for. To find out more, I contacted my friend Fu Xiaoqi, who writes about art and culture for the largest newspaper in northwest China, the Hua Shang. Born and raised in Heilongjiang province, Xiaoqi came to Xian nine years ago to study Chinese literature. She never left. “I was drawn by Xian’s cultural liveliness,” she told me. “Now, my parents have also moved down.”

Xiaoqi showed me around some of Xian’s newer and more offbeat attractions. One day we visited a business that’s producing high-end historical reproductions, including Tang-style tricolored ceramics, exquisite zithers, and outstanding calligraphy. We also toured a defunct factory complex on the outskirts of town, where a group of artists has set up workshops and studios amid concrete warehouses. The so-called Textile Town Art District is similar to Beijing’s Dashanzi area, though on a much smaller and less commercialized scale. Because the artists also live here, visits can feel a little voyeuristic: we spotted one painter hanging salted fish and squid to dry on a clothesline; another was cleaning out his bedroom. But we also found plenty to admire—abstract paintings, a range of modern sculptures, forms made of twisted metal—as well as a little café where we were the only customers. It occurred to me then that there was a lot more to Xian than I had suspected.

“It’s a headache running a hotel in Xian,” complained Michael Monks, the manager of the Golden Flower Hotel, where I was staying. “Most visitors come in summer so that they can add on a boat tour on the Yangtze, and most stay only two days. The problem is the fixation on the terra-cotta warriors; we need to market Xian as the birthplace of an entire culture.”

Situated in the Wei River Valley, the cradle of early Chinese civilization, Xian is one of the country’s oldest cities. It was just north of here that Emperor Qin Shihuang, who first united the warring kingdoms of China and began construction of the Great Wall, built his capital in 221 B.C. Changan, as Xian was then known, flourished for more than a millennium under successive dynasties. Its prosperity peaked during the Tang era, when arts and literature blossomed. China’s center of gravity shifted eastward thereafter, to Luoyang, Nanjing, and later Beijing—a trend that was only partially reversed during the Ming dynasty.

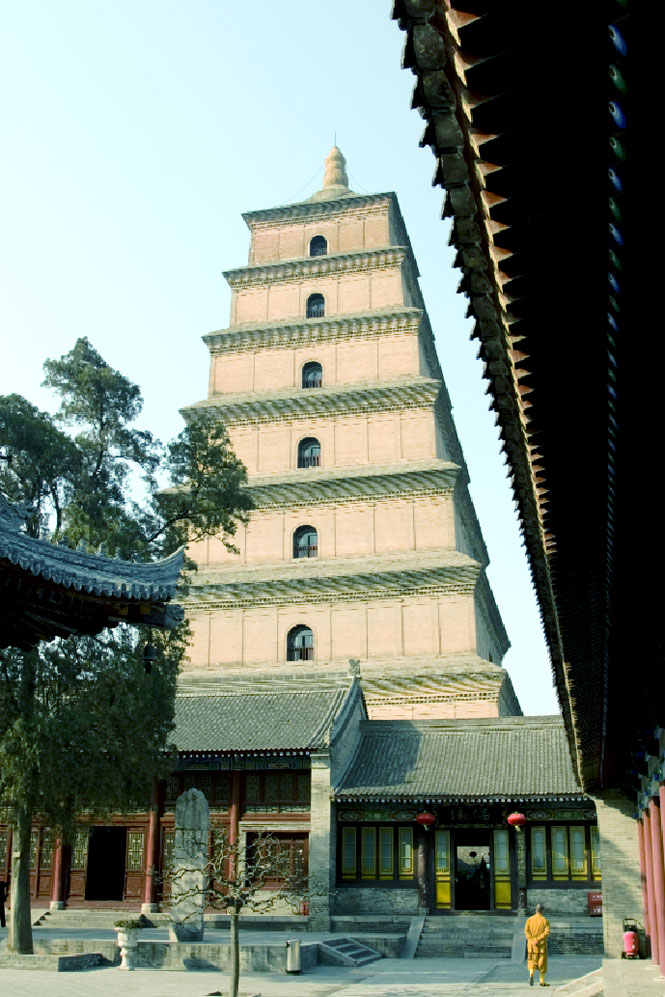

All this has bequeathed to Xian a wealth of historical sites, with tourist numbers to match; 31 million people visited in 2007. But most travel in organized tours on itineraries that follow a well-trodden circuit, including tourist traps (such as the Tang Paradise, a theme park where visitors are fed dumplings and superficial cultural shows) and a handful of major sites that are sadly overrun. One such place is the Big Wild Goose Pagoda, a seven-tiered tower of yellow brick that now hosts a garish, circus-like atmosphere, ruining the once serene Buddhist compound. Or the terra-cotta warriors museum itself, home to the thousands- strong, life-size “army” excavated from the tomb of Qin Shihuang. The scale of the collection is undeniably breathtaking, as are the finely shaped faces—each one unique—of the battle-ready soldiers. But the crowds and commercial clamor of the museum shatter any meaningful contemplation. Overcrowding is also degrading the clay; mold has been found growing on the figures.

And yet, during my 12 days in Xian, I found plenty of quieter sites to explore. I spent one morning on the 14-kilometer-long defensive wall that boxes in the historic core of the city. Originally built of rammed earth in the 14th century, it was bolstered with bricks in 1568 and then fully restored in 2007, when broken sections were seamlessly repaired. The restoration has made the wall whole again, and I happily circumnavigated it on bicycle. From the battlements, I also got a fine perspective on Xian old and new: within the wall, arrow-straight avenues (the city was originally laid out on a grid pattern) and a dense jumble of worn buildings; and beyond, the more airy fabric of the modern city, a forest of creamy or pinkish high-rises enveloped in the dusty haze that hangs over Xian.

Construction cranes were ubiquitous from my vantage point. The city’s population has now topped seven million (almost a quarter of the entire population of Shaanxi province, of which Xian is the capital), and a batch of buzzing new bars, cafés, and clubs has transformed it into the second-liveliest metropolis in central China, after Chengdu. Powering its economy are universities, tourism, and the Xian National High Tech Industries Development Zone. The latter is a swanky enclave to the south where wide, uncongested streets and shiny new office towers seem a world away from the town center.

On another day I visited the Chenghuang Temple, where monks are reviving Tang court music. There are no regular recitals as yet, but I was able to watch a video of the first concert held in many generations: an ensemble of drums, cymbals, flutes, violin-like erhu, and other wooden instruments that produced a thumping, flighty repertoire of sounds.

Like its music, the Chenghuang (literally, “city god”) has only recently emerged from the depredations of the Cultural Revolution. The 620-year-old Taoist temple enshrines the deified early-Han general Jixin, who, as the spiritual guardian of Xian, holds sway over pretty much everything, from natural disasters and commercial success to whether a baby is born a boy or a girl. Judging from all the pendants scribbled with names of worshippers in the temple halls, Jixin still has plenty of devotees. But he couldn’t stop the Red Guards in 1966 when they stormed the temple and smashed its religious icons, and then turned the grounds into a flea market.

Six years ago, the city government banished the market and reopened the temple; a multimillion-dollar restoration effort began in early 2008. Perhaps ironically, I found the temple all the more attractive in its weathered state, courtesy of a 40-year hiatus in maintenance. I’m not alone. According to senior abbot Liu Shitian, the old look will be retained and the wood won’t be painted over.

I was intrigued by the building’s elaborate timber roof supports —designed to be springy enough to withstand earthquakes (the temple survived a deadly quake in 1556, which killed 830,000 people)—and by the fine wooden carvings that proliferate throughout. These depict various animal motifs and floral themes. Some of the carvings are broken or chipped; a few are missing entirely. “Luckily,” Liu told me, “we have an old manual about the temple’s design, so we can faithfully recreate the missing carvings. But we struggled to find craftsmen capable of doing the job. We only managed to find a few artisans, and the youngest of them is 72.”

My appreciation of Xian’s imperial legacy deepened at the Shaanxi Historical Museum, where the government has spent a small fortune on an underground wing for Tang-dynasty murals. This is the largest of the city’s four museums, and I spent hours browsing the thousands of relics packed into its exhibition halls. Then I visited the new wing, which houses 200 murals dislodged from the tumuli of Tang emperors and empresses, painted with natural dyes on stucco. The colors are still vivid after 1,300 years, and the depictions offer vignettes of court life in a way few other relics can match: a game of polo; a sumptuous royal banquet; a lineup of willowy ladies (perhaps concubines) dressed in the finery of the time.

The murals are right up there with the terra-cotta warriors in terms of historical value. But perhaps even more impressive is another underground site: the Han Yangling Museum, situated 40 kilometers outside Xian off the airport expressway. The museum opened in 2007 at the tumulus of Han-dynasty Emperor Jingdi, who ruled from 188 to 141 B.C. The massive barrow has 81 burial pits fanning out from its central tomb. Many of these chambers, whose timber shorings collapsed long ago, are dedicated to a different royal ministry; Jingdi wished to be buried with a simulacrum of his entire state bureaucracy, in order to rule in the afterlife. So far, only 10 pits have been excavated.

It’s an impressive setup. Visitors walk on the glass floor set over the pits, peering down on the long trenches where an array of partially unearthed figures have been left in situ by archeologists. They poke out of the earth or lie strewn about; some are broken. There are also are clay pigs and cows and dogs, and urns of wheat that were supposed to sustain Jingdi’s entourage on its journey to the next life.

I returned to the Gao Fu house on my last night in Xian to take in an exhibition of traditional landscape paintings. The work was dense and claustrophobic—voluptuous mountains and gushing waterfalls, mist-wreathed forests and idyllic farmhouses—yet tempered by a transcendent gracefulness. Then I watched a shadow-puppet show in the house’s theater, a peasant love drama executed with euphoric oration, vivacious movement, and thumping traditional music, the timbre rising and falling.

Afterward, I sat in one of the Gao Fu’s four courtyards sipping tea, thankful for the high, thick walls that kept out the din of Muslim Street. As a tourist destination, Xian is not without its shortcomings. Few restaurants outside upscale hotels have English-language menus, nor do taxi drivers or bus conductors speak anything but Chinese. Traffic can be nightmarish. And so too can the weather: miserably hot in summer, punishingly cold in winter, chokingly dusty on windy days. But thanks to preservationists like Yang Shuanglin and the government’s newfound heritage ethos, the city has never been more compelling. I pondered this as the strains of a zither floated cross the courtyard, and the ghosts of old Xian stirred around me.

THE DETAILS:

Xian

Getting There

Xian’s international airport is served by daily Dragon Air (dragonair.com) flights from Hong Kong. Bangkok Airways (bangkokair.com) flies nonstop between the Thai capital and Xian on Tuesdays and Saturdays.

When to Go

Early spring and autumn, on either side of Xian’s peak tourist season, offer an escape from the oppressive heat of the summer months as well as the crush of crowds at the city’s main sites.

Where to Stay

Managed by Shangri-La, the Golden Flower Hotel (8 Changle Xilu; 86-29/8323-2981, shangri-la.com; doubles from US$124) is arguably the best five-star option here; rooms in the renovated north wing are plain but are well-appointed and good value. Its location outside the old city walls is a drawback, however. To be closer to the action, check into the Hyatt Regency Xian (158 Dong Dajie; 86-29/8769-1234; xian.regency.hyatt.com; doubles from US$95), which is set amid the town’s historic center.

Where To Eat

For a sampling of northern Shaanxi cuisine, head to Qiao Mai Yuan Fanzhuang (58 Hanguang Nanlu; 86-29/8827-8027). No-frills De Fang Chang (Zhonglou Guangchang; 86-29/ 8721-4060), located near the Bell Tower, is an institution for its jiaozi (dumpling) banquet, while Shang Palace at the Golden Flower Hotel provides a sophisticated setting for Muslim fare and Cantonese specialties.

What to See

Xian’s star attraction is the Museum of the Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses of the Qin Shihuang (Qinling, Lingtong County; 86-29/8139-9001; bmy.com.cn), which houses the excavations of the terra-cotta army built for China’s first emperor. Be sure also to visit the Shaanxi History Museum (91 Xiaozhai Donglu; 86-29/ 8525-4727; sxhm.com), where advance booking is required for the mural wing; and the Gao Fu House (200 Bei Yuan Men Xi; 86-29/8723-2897), a vast courtyard estate recently returned to its Ming-era glory.

Originally appeared in the May 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Rediscovering Xian”)