The Pantanal is the biggest swamp on the planet, a seasonally flooded expanse of grasslands, savannas, and tropical forests that harbors not only a unique cowboy culture but also the greatest concentration of wildlife in South America. From capybaras to caimans to jaguars, encounters with nature don’t come easier than this.

Photographs by Frédéric Lagrange

Sitting Sphinx-like on the riverbank, the young male jaguar was less than 10 meters away from where I perched at the front of our boat. As our eyes locked, I felt a rush of fear mixed with marvel that something could be so beautiful and dangerous at the same time. It was a weird sensation, being so close to a creature that wouldn’t have thought twice about having me for dinner. A clump of lily pads and a narrow stretch of murky water lay between us, but nothing the big cat couldn’t have leaped in a single bound.

That’s what makes the Pantanal wetlands of west-central Brazil so special—the chance for up-close encounters with wild animals. And not just jaguars, mind you, but also giant river otters, anteaters, howler and capuchin monkeys, tapirs, capybaras, caiman crocodiles, and the thousand different bird species that call this vast floodplain home. The Amazon to the north may have the reputation for being the place for wildlife in South America. But as my veteran guide Judy Drunha explains, “There are many animals in the Amazon, but you only hear them, rarely spot them, because the vegetation is just too thick. The Pantanal is much more open country. You can actually see the wildlife, and so many different kinds.”

The name of the region derives from pântano, the Portuguese word for swamp. And that’s basically what the Pantanal is, albeit a supersized one. During the seasonal flooding of the Paraguay River system from November to March, the plains are transformed into a seemingly endless web of interconnected swamps, lakes, lagoons, and channels that effectively cuts the Pantanal off from the rest of Brazil. Various sources call it the world’s largest tropical wetland or largest network of contiguous wetlands. Either way, it’s a huge expanse, spilling over into neighboring Paraguay and Bolivia across an area almost as large as Great Britain.

That’s an awful lot of water and wildlife. But not an awful lot of humans. Only about 30,000 people live in the Pantanal heartland year-round, mostly on the hundreds of isolated fazendas (cattle ranches) situated around the periphery of the swamps. The deeper you venture into the wetlands, the fewer people you come across, until you reach a point where mankind seems to have made little if any impact. Which is remarkable, given that so little of the Pantanal falls within the boundaries of national parks or wildlife preserves. Nearly all of it is privately owned, mostly by cattle ranching families who’ve lived in the region for generations. In fact, it is the deep connection between the ranchers and nature—and the ranchers’ stubborn resistance to outsiders trying to exploit their land—that likely spared the Pantanal from the environmental destruction that has ravaged so much of the Amazon.

From Campo Grande, a city of about one million people that serves as the gateway to the southern Pantanal, it took almost seven hours along increasingly rough dirt roads to reach my first destination. Founded in 1940 by the parents of the current owner, Baía das Pedras is a working cattle ranch that does double duty as a farm-hotel. It’s very much a family affair, as well as a great place to soak in the pioneering spirit of the region.

“When I was a child in the ’60s, my father used to take an oxcart once a year to get supplies from the nearest town, 180 kilometers away,” Rita Coelho Lima recalled as we sat on the porch of her ranch house that first evening. “It took a week to get there and 20 days to get back. They built all of this themselves, my mother and father—this house, the corrals, even the road you drove in on today.”

Although she had four older brothers, Rita was expected to contribute her fair share while growing up at Baía das Pedras. “I learned all the cowboy skills,” she said proudly. “How to ride, how to rope, how to brand. And I can run a cattle drive if need be.”

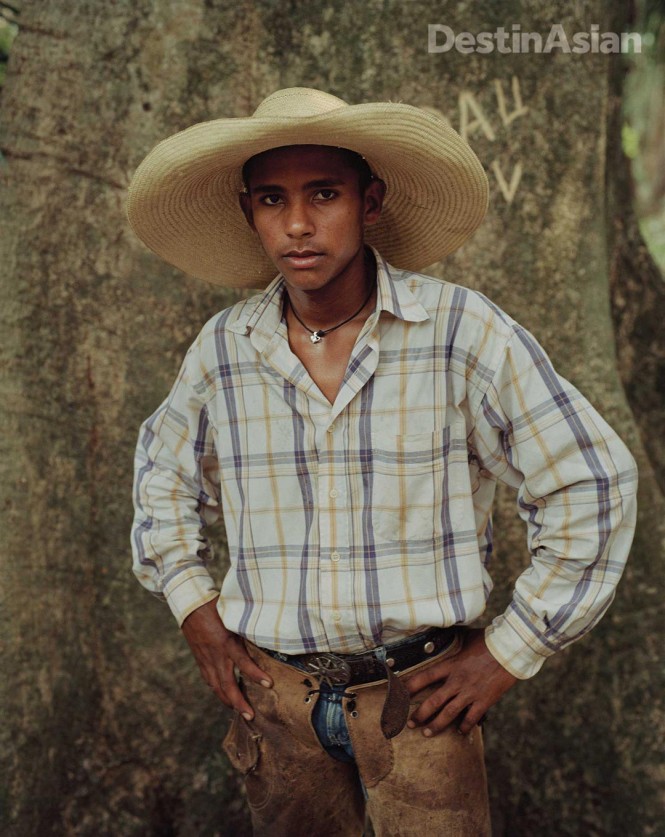

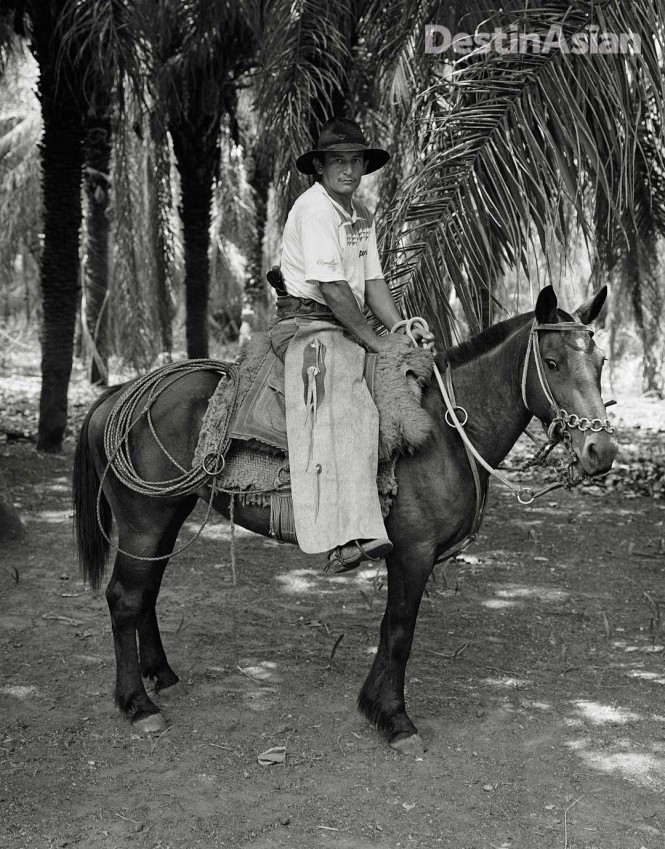

The discovery of gold in the highlands around the Pantanal attracted a wave of settlers in the 1720s. When the yellow metal ran out, most of the prospectors trickled back to the coast. But a hardy few decided the empty grasslands were ripe for cattle ranching. Over the centuries, a distinct Pantaneiro cowboy culture evolved, a lifestyle that revolves around cattle and horses. “Our horses have special adaptations,” Rita related. “They can stand in water a week or a month at a time and their feet don’t get disease. They can stick their heads into the water and eat submerged grass. No other horses in the world are like that.”

Although most of the hands at Baía das Pedras are young and transient, a few have been around for nearly as long as the ranch itself. Sebastião Ramão, his skin burnished and tough as leather, has worked here since he was a teenager in the 1950s. Semi-retired these days, he still lives in a cottage near the horse corrals.

“We had lots of fun in the old days,” Ramão told me. “Whenever we castrated the cattle, we had a big fiesta. Beer, food, lasso competitions, horse races. I used to do very well at horse racing—200 meters in a straight line. I wasn’t bad at calf roping either. And every cowboy had three or four wild horses they had to break. You’d catch them in the bush, bring them back, and break them within six months to give to the ranch owner.”

Despite the presence of a television and satellite dish, Ramão continues to cherish Pantaneiro traditions. Like the tereré herbal tea that he sipped during our chat; or the tanned hides stretched on wooden frames on his porch, which he’ll use to make saddles and other horse tack; or the ancient turntable on which he plays his collection of moda de viola Brazilian cowboy records. “I don’t listen to bossa nova or samba,” he laughed. “It has to be country.”

Exploring Baía das Pedras by horseback and truck with other guests, I snatched a glimpse of several tapir (the largest mammal in South America) and puma tracks running down the middle of a dirt road. Every water body seemed to have hundreds of caimans sunning themselves amid the lily pads and muddy banks; with an estimated 10 million of the reptiles, the Pantanal is thought to harbor the world’s largest crocodilian population.

We also encountered several giant anteaters. Growing to the size of a large dog and equipped with a darting, sticky tongue, these bushy-tailed creatures are also armed with Godzillian claws that they use to dig for ants and termites and to fend off predators. They are, I’m told, the only animal that can thwart a jaguar or puma attack, a fact that popped into my mind as one wandered to within an arm’s length of where I was crouched behind a bush, camera in hand. I froze and held my breath, but the big hairy thing got a whiff of something, raised its ridiculously elongated head, and veered away just in time.

The next morning I woke to a racket of squawking birds outside my room in the ranch house—hyacinth macaws greeting sunrise over the Pantanal. Grabbing my binoculars, I stumbled into the yard to get a better look, joining a group of guides and fellow guests who had already gathered for the early-morning spectacle. “And to think we nearly lost them,” said Harsha Javaramaiah as we watched the gorgeous blue-and-yellow parrots glide between the trees.

An avid Indian birder and wildlife expert who guides trips in the Pantanal for Florida-based Terra Incognita Ecotours, Javaramaiah explained how the macaws were saved from almost certain extinction in the 1990s by a young biologist named Neiva Guedes, who wrote her master’s thesis on the birds’ rapid disappearance in the wild. Guedes discovered that one of the main reasons for their population decline was the destruction of manduvi trees, in whose hollows they typically build their nests; ranchers routinely cut down the trees because the fruit caused cattle to miscarry. Other factors included a low survival rate among chicks and rampant poaching fueled by the illegal pet trade. Her findings led Guedes to start the Hyacinth Macaw Project, a breeding program based out of the Refúgio Ecológico Caiman, a wildlife refuge established by another ranch in the southern Pantanal.

“Neiva invented a wooden box that you could hang in any kind of tree to mimic the bird’s nest,” Javaramaiah told me. “She used climbing equipment to go up into the trees and hand-feed the chicks so they would survive. She also campaigned for stricter enforcement against poaching. Since her project began in the early ’90s, the hyacinth macaw has bounced back in spectacular fashion.”

I found this merging of ranching, tourism, and conservation work to be as unexpected as it was compelling. For its part, Baía das Pedras supports wildlife research projects by supplying room and board to scientists studying the giant armadillo and South American tapir. Every day at breakfast, the armadillo squad would roll into the dining room after another all-night vigil to observe a creature that can grow up to 80 kilograms. I asked one of the researchers about my chances of spotting one in the wild. He looked around at his colleagues and laughed. “Not unless you want to spend weeks squatting in a muddy hide getting bit by a million mosquitoes.” Given that I was heading into jaguar country later that day, I hoped finding big cats wouldn’t prove as difficult.

The single-engine Cessna took off from the grassy airstrip at Baía das Pedras and headed north across the middle of the Pantanal. From the air, the floodplain’s unique geography came into focus, a giant jigsaw puzzle of grass and water stretching as far as the eye could see in every direction. The only “roads” were rough tracks made by zebu cattle moving between pastures. Otherwise, the landscape appeared untouched. The farther north we flew, the greener and wetter the terrain became, until a pinprick of civilization finally appeared on the horizon: Porto Jofre, the only settlement of any kind in the heart of the wetlands.

Over the past 30 years, Porto Jofre has grown from a remote fishing camp on the Cuiabá River into a jumping-off point for sport fishermen, photographers, and wildlife groupies heading into the northern Pantanal. It’s also the end of the line for the Transpantaneira, a dirt highway that runs 146 kilometers due south from the old gold-mining town of Poconé. The road was originally intended to extend all the way across the wetlands to Corumbá on the Bolivian border, but the engineers who worked on the project in the 1970s were unable to overcome the hydrological challenges brought on by the Pantanal’s seasonal flooding. “It would have taken a Dutch-style dike and reclamation job to drain the area,” our pilot said as we buzzed the highway on the approach to Porto Jofre. “They decided it wasn’t worth the effort. Or the money.”

Checking in to the riverside Pantanal Norte Hotel, I’m advised not to stroll around after dark—jaguars are rare in Porto Jofre, but not unheard of. Less worrisome are the many other creatures that frequent the grounds: toucans and caracara raptors, grazing capybaras, and the caimans that bask on the muddy banks beside the boat docks.

Still, I was here to see jaguars, which proved easy enough after joining guide Judy Drunha for a speedboat ride upriver to a marshy delta area where two smaller rivers flowed into the Cuiabá. The first sighting was of a young female stealthily making her way through the vegetation on the right bank. She was clearly on the hunt, and it didn’t take her long to spot potential prey—a caiman resting in shallow water. In the blink of an eye, the jaguar pounced, a blur of black and orange followed by a massive splash. But the caiman was even faster, and the big cat exited the river sopping wet and looking more than a little flustered. Farther along we watched her stalk a family of capybara lounging on a beach. They too escaped. Finally, she managed to bag a caiman, her persistence paying off with a hefty meal.

During the hour we spent tailing her, the jaguar didn’t seem the least bit fazed by our presence. “They’re used to boats,” Drunha explained. “Fishermen have been coming here for years and tossing them fish, so they don’t run away when a boat comes close.”

It’s not just habituation that makes the Pantanal such an awesome place to see jaguars in the wild. Their population is also growing. According to Drunha, their numbers have increased from about 400 when she first arrived here from northern Brazil in the early 1990s to around 1,000 today.

Over the next four days we encountered a dozen more Pantanal jaguars, which, thanks to the abundance of prey, are well fed and thus considerably larger than their cousins elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere. Some were on the hunt, others were just snoozing on the shore. One afternoon we saw a mother and two cubs swimming across the Cuiabá, a distance of at least 100 meters. They made it look effortless.

As docile as the big cats can seem at close range, locals are quick to remind you that they can also be deadly. At least two people have been killed by jaguars in the Pantanal in recent years—a Brazilian fishermen camped along a riverbank, and a camera-toting tourist who insisted on snapping an even closer shot. “The jaguar jumped into the boat,” Drunha said. “All it takes is one swipe of those paws and you’re dead.”

However, such incidents are no longer a death sentence for the jaguar. The Pantanal stayed off the grid long enough for the tide to swing in favor of conservation in Brazil.

“In the old days, people used to shoot big cats to keep their cattle safe,” rancher Carlos Jurgielewicz had told me back at Baía das Pedras. “But that doesn’t happen anymore, at least not in the Pantanal. The new generation has a different attitude toward wildlife. There is much more awareness about nature and preservation than when I was a boy. We now realize that showing animals is far more beneficial than shooting them.”

THE DETAILS

Getting There

Fly to Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo for the onward flight to Campo Grande or Cuiabá, the respective gateway cities to the southern and northern Pantanal.

When to Go

It is almost impossible to visit the Pantanal during the November–March rainy season, when most roads are impassable. That leaves April though October as the best time to visit, especially the July–September period when wildlife viewing is at its best.

Where to Stay

Located around 300 kilometers from Campo Grande, Baía das Pedras offers comfortable digs, great food, and good company on a working ranch in the southern Pantanal. It’s accessible year-round via small plane but can only be reached by road during the dry season, a seven-hour journey. Activities include guided horseback rides through the swamps and game drives in open-topped, safari-style trucks across the grasslands; canoeing, fishing, and hiking can also be arranged. Evenings are reserved for sundowners at the bar and group meals around the big table in the ranch house (55-67/9912-8323; three-night packages from US$700 per person).

Hotel Pantanal Norte is the oldest and largest lodgings in Porto Jofre. Located on the riverfront, it features 28 modest but comfortable guest rooms, a swimming pool, and guided fishing trips and speedboat safaris into the surrounding wetlands (55-65/3637-1263; three-night packages from US$1,600 per person).

Tours

Most visitors will find it easiest to book an all-inclusive tour that includes transfers from Campo Grande and/or Cuiabá city. Recommended is Terra Incognita Ecotours’ nine-day Pantanal trips, which span both the northern and southern wetlands (US$7,700 per person).

This article originally appeared in the February/March 2017 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Brazil’s Wild Wet”).