Above: The Museum of Islamic Art occupies an artificial island in Doha Bay.

I. M. Pei’s latest creation—the Museum of islamic Art in Doha—is a masterpiece of Modernist design, and a fitting tribute to the world-class collection within

By Jamie James

Photographs By Martin Westlake

Islamic art requires quiet contemplation. Given to abstraction, rarely focusing on the outward appearance of earthly things, it doesn’t grab the retina but rather invites viewers to find their own way into the work. For Michelangelo, God was in the face of a virile, benevolent old man with a beard; the Islamic artist could find the divine in the symmetry of a geometric pattern. As a result of this intellectual challenge, 14 centuries of Muslim art has been largely underappreciated and poorly understood by the outside world.

A new museum in Doha triumphantly proves that this art of the mind and the soul can be as rich and rewarding as that addressed to the eye. Opened this past December, the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) is housed in a magnificent building by Modernist master I. M. Pei and makes an immediate, undeniable claim to a place in the first rank of world museums. It’s the best and boldest move yet by the tiny, oil-rich emirate of Qatar in its campaign to create an instant culture on a sandy peninsula in the Persian Gulf.

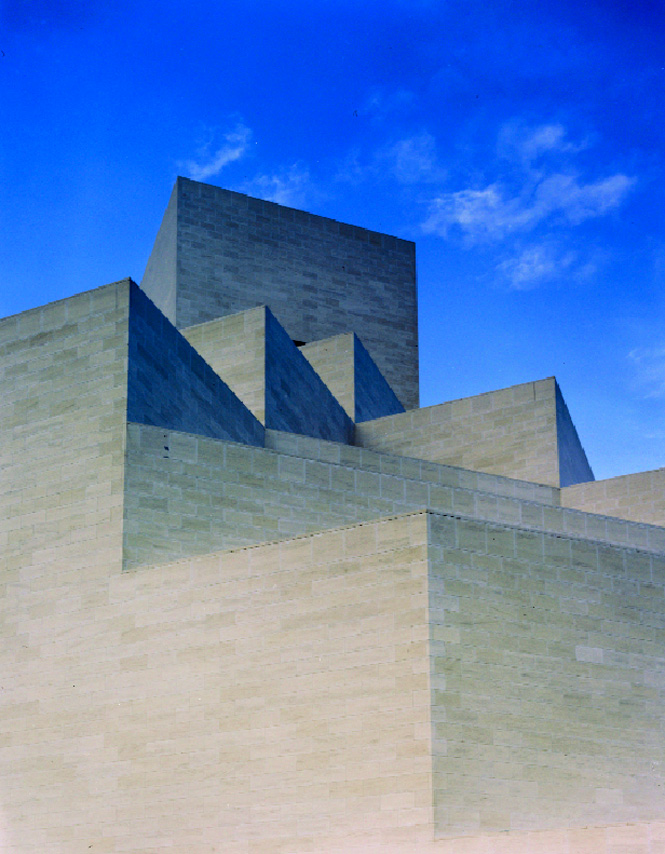

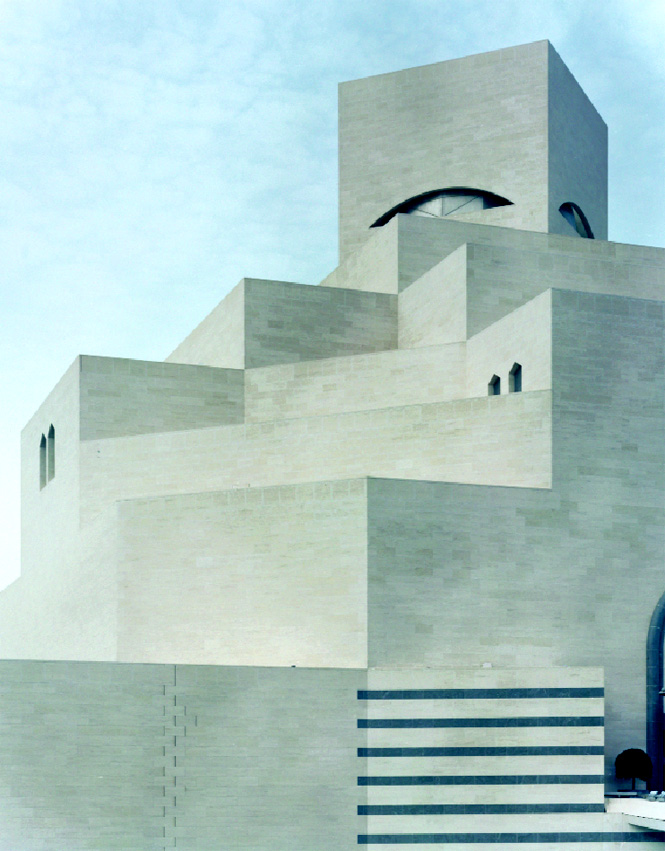

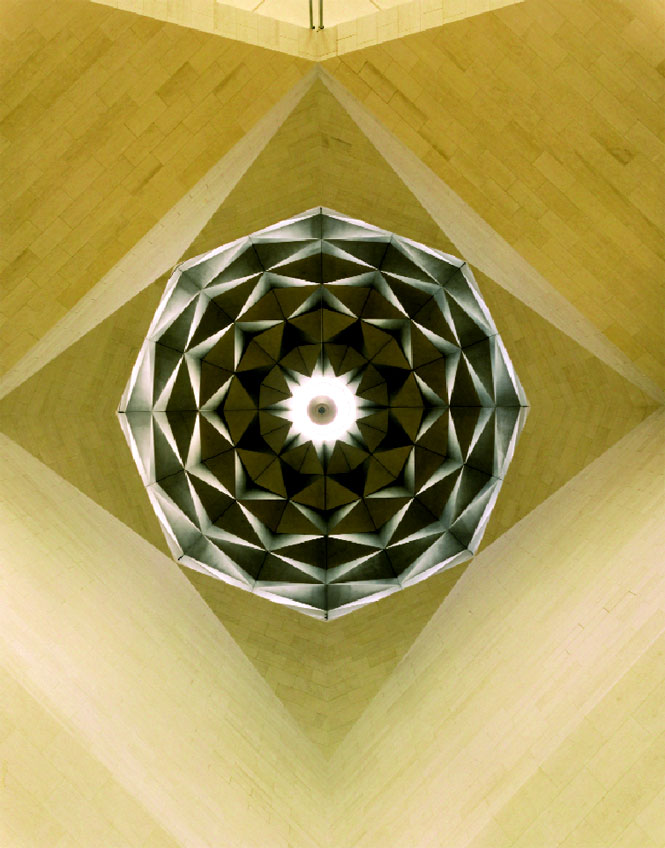

Built on an artificial island in the city’s harbor, the museum rises like a mathematician’s radiant, rational dream. The visitor approaches the main building from Doha’s Corniche road, along a 60-meter causeway lined with date palms. Inside, the soaring atrium draws the eye upward to a faceted geometric dome—toward the light, to the heavens. Filtered sunlight floods in from windows rising floor to ceiling on the atrium’s north side. Exhibition galleries surround it on four floors (of which three are presently open to the public), filled with some 800 objects: paintings and sculptures, manuscripts and textiles, ceramics and jewelry, weapons and scientific instruments.

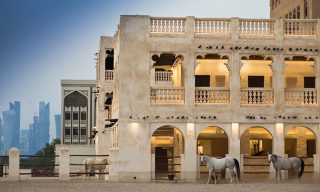

West of the main building, a terrace cooled by fountains and towered over by a pair of gracile lanterns leads to a boat landing, which is reserved for the exclusive use of the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, the museum’s patron. On the eastern side, an arcade lined with potted topiary leads past a cloister-like courtyard to the museum’s library and educational facilities. By year’s end, a crescent-shaped landfill enclosing the complex will be transformed into a public park—a welcome addition to a city where green space is a precious commodity.

Unlike other new museums built in recent years, Pei’s building doesn’t put its own style on display to make a sensational impact, thereby threatening to overpower the objects it shelters. In Doha, the architect has effaced his presence and shifted the focus to the play of pure, enveloping light. Pei, whose best-known museum work is the controversial glass pyramid he designed for the 1989 expansion of the Louvre, explained the challenges of his latest project at the MIA’s opening. “This was one of the most difficult jobs I ever undertook,” he said. “It seemed to me that I had to grasp the essence of Islamic architecture.”

That may sound like hubris, but the architect, now 92 years old, approached the assignment with the humility and methodical care of a good student. Pei has never been interested in making “statements,” but rather in creating architecture that works. From the beginning, he was aware of the challenge he faced. “The difficulty of my task,” he recalled, “was that Islamic culture is so diverse, ranging from Iberia to Mughal India, to the gates of China and beyond.” Like a medieval pilgrim, Pei visited the most famous mosques of the Islamic world, from the Grand Mosque in Cordoba to the Jama Masjid in the 16th century Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri, near Agra. His quest finally ended in a courtyard of Cairo’s Ahmad Ibn Tulun mosque, where he was entranced by a modestly proportioned sabil—a fountain for ablutions—sheltered by a simple dome atop stepped, rigorously cubic pendentives. “This severe architecture comes to life in the sun,” he said, “with its shadows and shades of color. I had at last found what I consider to be the very essence of Islamic architecture, in the middle of the Ibn Tulun.”

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in Guangzhou in 1917 and grew up in a landmark house in the Classical Gardens of Suzhou, now listed as a World Heritage Site. Pei’s eye was formed in the Lion Forest Garden, where miniature rock landscapes, originally collected for an early Zen temple, evoke the harmony of classical Chinese poetry—a harmony evident in his best work. He went to the United States at age 18 to study at the University of Pennsylvania, and later received architecture degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, where he studied under Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus movement. Pei became an American citizen in 1954.

Schooled in the International Style of architecture, Pei made his mark on the skylines of the world’s great cities, from his Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong to the Four Seasons Hotel in midtown Manhattan. He had created several museum designs before he took on the Louvre, notably the widely admired East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1974. After he retired from the leadership of his New York–based firm, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, in 1990, he made museums a specialty, from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, to a modern art museum in Luxembourg. The Suzhou Museum, a brilliant rebirth of classical Chinese aesthetics in a Modernist vernacular, was hailed as his final masterpiece when it opened in 2006. Now attention shifts to Doha. Whatever superlatives may be heaped upon the Museum of Islamic Art, no one should be so foolish as to call it the “final” anything of I. M. Pei’s prodigious career.

An architect’s first important decision—often, the most important of all—is where to build. The Qatari capital offered Pei a number of sites for the museum on the Corniche, the coastal road that curves along the perfect half-circle of Doha’s waterfront, but he rejected them all, fearful that in the future skyscrapers might be built that would rob his design of its most essential commodity, sunlight. So he asked if he could create his own site, an artificial island in the harbor. “This was very selfish of me, of course, but I knew that in Qatar it is not too complicated to create landfill.”

The stepped motif of the Ibn Tulun sabil dominates the razor-sharp outlines of the museum’s central mass. Pei came to the conclusion that “the essence of Islamic architecture is in the desert sun, which brings strong volumes to life in a changing play of light, shades, and shadows.” Adhering rigorously to this principle, the building’s white limestone exterior makes a powerful initial impact, dazzling the eye. The experience only deepens when one enters the museum. The great volume of filtered light in the atrium has a ritual cleansing effect, making it rather like a sabil of the mind’s eye, preparing the visitor for the spiritual experience of viewing the collection.

In the Museum of Islamic Art, God is in the details. A large circular lamp magically hangs in midair over the center of the atrium, perforated with geometric motifs in the Egyptian style; these motifs are echoed in miniature in the elevator ceilings, which are also modeled on the stepped pattern from Ibn Tulun. Even the palm trees lining the causeway had to be just so: Pei decided that Qatari trees weren’t tall enough, so he imported 104 date palms from Saudi Arabia. According to the architect, this was the only time he had a disagreement with the emir.

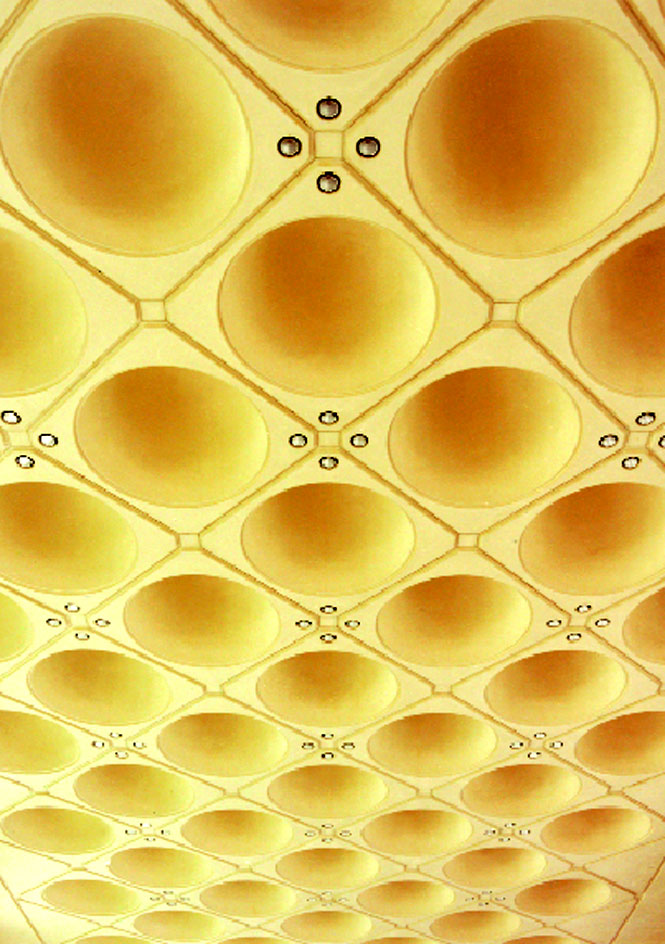

Upon entering the building, most visitors are so overwhelmed by the impact of the atrium that they wander around it for a while before proceeding to the galleries. Inevitably, the doubt grows: Can the collection possibly live up to the architecture? The affirmative answer presents itself as soon as you step inside the galleries, and grows firmer as you move from one space—and one masterpiece —to the next. Jean-Michel Wilmotte’s interior designs, simple and sumptuous, illuminated with theatrical precision by spotlights, create a tranquil atmosphere of repose; a sense of retreat from Pei’s flood of light, like the profound gloom of a Bedouin tent at midday. In this setting, the collection gleams like a radiant treasure trove in a cave from a tale in The Arabian Nights.

The museum’s holdings reveal themselves to be on a par with the greatest of their kind in the world: those of the Metropolitan Museum in New York; the Louvre; and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert, both in London. Almost every object is of exceptional quality. Says Oliver Watson, the MIA’s director, “The museum is the first substantive architecture and collection of international quality devoted to Islamic art. The collection provides a conspectus of the field.” That’s a scholar’s understatement. What he means is that the museum has strong holdings in every major category of Islamic art in terms of geography, historical period, and artistic medium, making it an essential destination for academics worldwide. In some ways the most remarkable aspect of the MIA collection is that it was begun just 20 years ago, under the patronage of Qatar’s royal family.

Before he was appointed to this post, Watson was Keeper of Eastern Art at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Prior to that, he had been the chief curator of Middle Eastern collections at the Victoria and Albert. The collection in Doha was mostly formed by the time he arrived. His first important task was “mapping” the museum, choosing and grouping the objects for display. The piece that Watson chose as the first visitors would encounter isn’t a spectacular sculpture like the Louvre’s Winged Victory of Samothrace, but a humble bowl, 20 centimeters in diameter. It is creamy white, with a calligraphic inscription in cobalt blue running from the right edge to the center. The design is simple and superbly elegant, much closer in sensibility to 20th-century Modernism than to anything in antiquity.

“Every object is a node, where countless interesting stories converge,” Watson explains. Of the bowl, he says, “It was made in Iraq, probably in Basra, in the ninth century. It is an indication of a rising middle class.” The clerical and commercial classes in Mesopotamia had disposable income with which to purchase objects proclaiming their social status, but they couldn’t afford gold or silver. “Chinese ceramics had begun to be imported at the end of the eighth century, and the potters in Basra thought, ‘We can do that.’ The calligraphic message reflects that pride.”

There are two ways of interpreting the inscription, according to Watson. The first reading is: “What was done was worthwhile.” The alternative, considerably less poetic, is “Made by Salih,” the name of the potter, who wanted to get his brand out there, like a modern designer handbag from Milan. Salih had good reason to be proud: the blue cobalt oxide pigment used for the inscription is a major Islamic innovation, predating Chinese blue-and-white ceramics by centuries.

The intense focus on calligraphic expression is another important theme converging in the Basra bowl. Created in the second century of the Islamic era, it reflects the new civilization’s search for a visual style. “What did Islam have to offer that was unique?” Watson asks. Ancient Greek and Roman artists, and later Byzantine Christians, had created glorious representations of the human figure in sculpture and mosaics; farther east, Hinduism and Buddhism had already produced great mystical traditions. In Arabia, there was little in the way of a preexisting tradition of the visual arts to draw upon; the principal native expression was in poetry. “The Word emerged as the vehicle for carrying the message of Islam,” the curator concludes. “It was one of the great acts of branding in history.”

In addition to affirming this logocentric basis of Islamic art, through his mapping of the collection, Watson was also intent on showing that it encompasses much more than the refined, highly intellectual calligraphic works and geometric patterns usually associated with the term. “A lot of it is secular, with representations of the figure and living creatures,” he says. Visitors in search of dazzle will want to linger over a gold falcon from 17th-century India, 23 centimeters high, enameled and encrusted with hundreds of emeralds, rubies, and diamonds carved to represent the bird’s feathers. A finely woven carpet from Hyderabad rolls out to a length of 16 meters, a masterpiece of color and pattern too large and complex to be taken in with a single glance; the carpet’s symmetry emerges in the viewer’s mind.

Many fascinating objects are modest in scale. One of the most arresting works here, signed and dated by the Indian artist Farrukh Beg in 1615, is a watercolor portrait, enlivened with gold leaf, of the Christian saint Jerome, after a painting by the German master Albrecht Dürer.

It is an early, sophisticated example of Occidentalism, the fascination in the East with Western subjects, mirroring Orientalism, exotic images of the East in Western art. Which prompts the vexed question: What is Islamic art? If a painting of a Christian saint can be considered Islamic, then are the highly romanticized and eroticized paintings of Oriental subjects by European painters in the 19th century examples of Christian art? It’s an imperfect analogy, of course. The European Orientalists painted pictures of nubile maidens in exotic settings to titillate the jaded palates of bourgeois collectors, whereas Farrukh Beg was a highly refined artist at the court of Shah Jahan, the builder of the Taj Mahal and Delhi’s great Jama Masjid. If it surprises us to learn that the court of a Muslim emperor embraced such cosmopolitan interests, that’s merely a reflection of our own provincialism. According to Watson, Islamic art “as it has been called by everyone studying it over the last century and more, is shorthand for art from the Islamic world—in other words, art produced in countries under Muslim rule.”

He hopes that the MIA will strike a blow against what he calls the “unfortunate misconception that Islamic civilization is a violent, backward-looking culture.” Watson describes 10th-century Cordoba as being among the most civilized places in the world of its time, with parks and palaces, schools and libraries filled with exquisite expressions of the culture. “Ottoman Istanbul in the 16th century was as cultivated, tolerant, and outward-looking as any place on earth,” he says.

Qatar has made an ambitious, intelligent attempt to imitate the tradition of these ancient Muslim capitals. The city of Doha has been raised with dizzying speed, the skyline reflecting the soaring oil markets of the recent past. Now the country is seeking to create an identity for itself beyond petroleum wealth. Professional tennis and golf tournaments have contributed; last year Robert De Niro announced that he would expand his Tribeca Film Festival to Doha, beginning this November. Of more lasting benefit to the people is Education City, a 14-square-kilometer complex on the outskirts of Doha that houses branch campuses of major American universities, including Cornell, Georgetown, and Carnegie Mellon.

If the emirate’s intent with the Museum of Islamic Art was to create an enduring symbol for its modern raj, a national icon like the Sydney Opera House, it has a good prospect of succeeding. Yet regardless of whether Doha becomes a major destination for leisure travelers, it’s already a must for anyone with a serious interest in Islamic civilization.

THE DETAILS:

Doha

Getting There

Qatar Airways (qatarairways.com) operates twice-daily flights to Doha from Hong Kong (except Sundays and Tuesdays) and Bangkok, and daily flights from Singapore and Kuala Lumpur.

When To Go

Like the rest of the Gulf, Qatar has stiflingly hot summers; October through April offers milder weather. The Tribeca Film Festival Doha is scheduled for November 10–14.

Where To Stay

An elegant high-rise across Doha Bay from the Museum of Islamic Art, the 232-room Four Seasons Hotel Doha (Al-Corniche; 974/494-8888; fourseasons.com; doubles from US$522) blends arabesque domes with Qatari wind towers and Moorish elements inspired by the Alhambra. Amenities include a private beach and marina, an excellent Italian restaurant, and a spa equipped with a hydrotherapy lounge and ice rooms.

Nearby, the newly opened W Doha (West Bay; 974/453-5353; starwoodhotels.com; doubles from US$335) is as cutting-edge as you would expect from a W, with familiar signatures like a living-room-style lobby and a Bliss spa augmented by a caviar room, a sultry shisha lounge, and Asian street food à la star chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten. Only time will tell whether staid Qatar is ready for W’s brand of jet-set glamour.

The vibe is more traditional at the city’s first luxury resort, Sharq Village & Spa (Ras Abu Aboud St.; 974/425-6666; sharqvillage.com; doubles from US$450), where guests are accommodated in a series of richly furnished villas modeled after Arabian courtyard houses, many with private terraces and water views. The museum is just a 10-minute drive away.

What To See

After touring the Museum of Islamic Art (Al-Corniche; 974/ 422-4444; mia.org.qa; closed Tuesdays), history buffs will want to visit the Qatar National Museum (974/444-2191; heritageofqatar.org), a former palace that houses archaeological treasures and Bedouin artifacts.

Explore the renovated Souk Waqif (Souk Wakif St.; soukwaqif.com), Doha’s traditional market area, for souvenirs, textiles, and a growing number of contemporary art galleries.

Originally appeared in the May 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Reflected Glory”)