Among the world’s first fusion foods, authentic Goan cuisine is getting harder to find these days. Thankfully, a handful of restaurants are committed to preserving the cross-cultural flavors of India’s smallest state.

Photographs by Christopher Wise

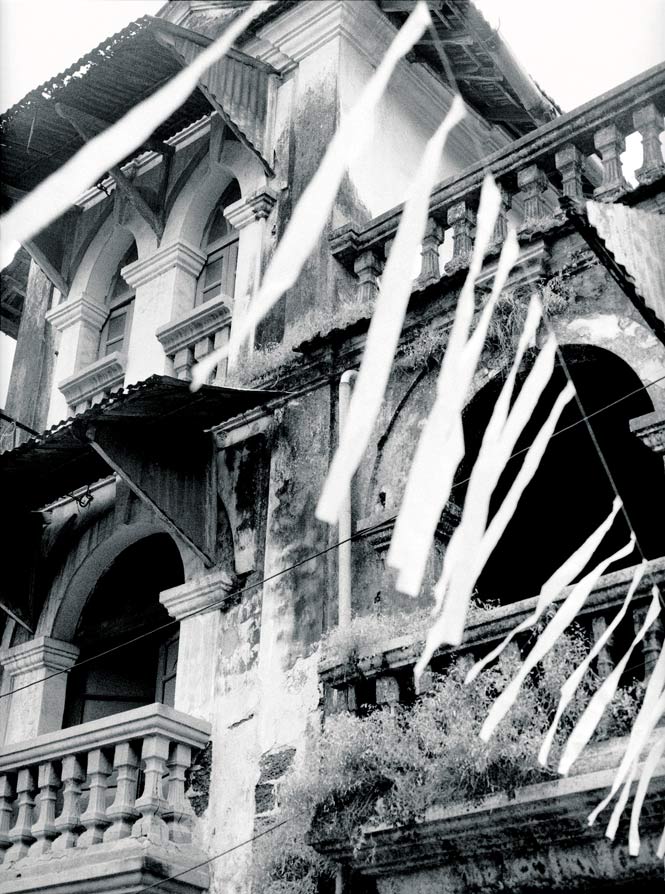

Two years ago, I wandered out of my hotel in Panaji, the snail’s-pace capital of Goa, and down 31st January Road into the old Latin quarter of Fontainhas. I passed villas enshrouded by bougainvillea and a procession of Catholic schoolkids skipping home in neat uniforms. A lonely chapel framed an empty alleyway. Then I spotted a sign: an inelegant, fluorescent thing that pointed me down a lane toward the hum of contented chatter. I would follow that sign for each of my four remaining dinners in Panaji. The restaurant it advertised, Viva Panjim, was just that good. I’ve been yearning to return ever since.

I’m back in Goa now, here to spend a week in and around Panaji eating my way through the local cuisine, and Viva Panjim is my first stop. Things haven’t changed a bit. Dressed in a prim brown blouse, the owner, Linda D’Souza, is presiding over her cheery little dining room with proud concern, like a schoolteacher watching her students on the first day of exams. I study her face for a flicker of recognition—two years ago I fawned over her food, took lots of pictures, and swore to return and write about it. She doesn’t seem to remember me, but she’s still an eager host, and promptly ushers me to a corner table.

“So what will you have, young man?” she asks. “How about the chicken cafreal? Oh, it’s very good today. I grind the spices myself every morning, you know.”

“Actually, I was thinking of having some seafood …”

“Of course—excuse me for being so dull!” Linda says, blushing. “Of course you want seafood. It’s Ash Wednesday!”

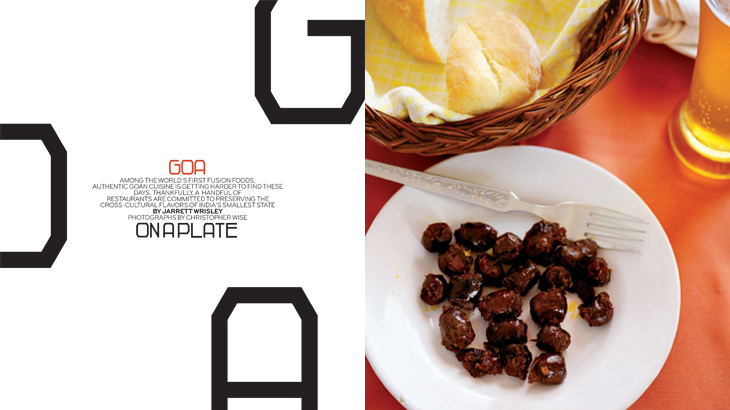

I don’t have the heart to confess to her that I’m not Catholic, so I just nod mechanically, order a cold Kingfisher beer, and wait for my feast to arrive. First come mussels rolled in spices and sautéed just short of crisp, which keeps them perfectly tender on the inside. Then I have a plate of oysters dusted in semolina flour with sharp black peppercorns, pan-fried to a satisfying crunch. Finally, there’s the pomfret—a small, firm-fleshed fish fresh from the Arabian Sea, stuffed with a rechado masala chili paste and grilled. It was smoky without, spicy within, its flesh the perfect measure of sweet.

I finish it all with a glass of McDowell’s Single Malt—a locally made whiskey that is worth seeking out—and sigh. Panaji is indeed a place to return to.

Panaji might well be India’s quietest state capital. Wrapped around the wide Mandovi River some 580 kilometers south of Mumbai, it’s certainly one of the quaintest. In its older neighborhoods, Indo-Portuguese houses are painted in bright Mediterranean colors—yellow, purple, sea green, pink—and a grand old church with a whitewashed Baroque facade, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, looms over the town square. Yet most tourists, on their way to Goa’s famed shorelines, pass though Panaji without giving it so much as a glance. This is fortunate; it has allowed the place to hold on to much of its original character, unlike the sprawling beach towns with their sarong hawkers and tattoo parlors and full-moon parties.

On my second day in Panaji, I meet with Rahul Goswami. A handsome, soft-spoken economist from Mumbai, he studies the effects of globalization on the Goan economy. He also writes about the environmental and social problems that India’s smallest state is now facing. “Charter tourism has created a great strain on resources here, on water and waste disposal and even culture,” Goswami tells me. “The beach belt of Goa is really an example of what shouldn’t be done to promote tourism. Very little good comes from it.”

He’s right. Goa, whose palm-draped floodplains glow green with rice and other crops, is beginning to brown. Garbage is piled on the roadsides, as the state has yet to create a public waste-disposal system. And many landowners have let their rice paddies go to seed, turning their energies to guesthouses instead. Vast tracts of farmland lie parched and buckled under the midday sun.

“When I first came here in the early 1980s, there were 26 varieties of rice available in markets,” Goswami recalls. “Many of them were native red-rice varieties, the kind you might only find in Goa and India’s other southern states. Now, you’re lucky if you can find two.”

At that moment, this story comes sharply into focus. I will sniff out the heart of old Goa by finding the best food this place has to offer. And by food, I don’t mean the dumbed-down tandoori served up to tourists, or the dosas or vegetable thalis sold in Tamil coffee shops to an increasing number of migrants from elsewhere in India. I mean Goan food, particularly the Catholic kind, a hybrid cookery that combines Hindu roots and Latin techniques with piquant local flavors and ingredients from Portugal’s former colonies, from Angola to Brazil. It’s a culinary style that, like much of traditional Goan culture, is being threatened by changing lifestyles and demographics. But it’s there if you know where to look: history on a plate, the past fixed right on the end of your fork.

“Hello, I’m looking for Maria de Lourdes …”

I look down at my notebook again, clear my throat, and recite with more confidence, “Hello, I’m looking for Maria de Lourdes Bravo da Costa Rodrigues.” Breathe.

In this narrow aisle of Panaji’s venerable Central Library, in a row just wider than my shoulders, shelves of dusty old books rise high to the ceiling. They cradle accounts, mostly in Portuguese, of Goa’s four and a half centuries of colonial rule, which began shortly after the arrival of Vasco da Gama in 1498 and ended with the “liberation” of Goa by the Indian Army in 1961. I’ve come here to meet the lady who knows and loves this collection best.

“You can call me Lourdes,” says a compact woman with spiky salt-and-pepper hair as she emerges from behind the stacks. She pauses to glare at an obstreperous child, silently shaking a finger. “Please, come to my desk.”

Apart from being a senior librarian, Lourdes is an accomplished local historian. In her youth, she spent a year studying in Portugal, and returned to Panaji with a greater understanding of the country that shaped her own, distinct culture. She is one of few at the library who still reads Portuguese, and has written extensively on traditional Goan cooking and social history. Most importantly for me, she is a walking encyclopedia of food. I offer to take her to lunch, and she obliges.

Lourdes is a busy woman; tonight, she’s cooking a meal for some visiting Brazilian professors, and so I get her for only an hour. I tell her that I’d like to eat vindaloo, the classic Goan pork curry cooked with vinegar and chili. “Then we must go to Riorico, at the Hotel Mandovi,” she says. “It’s just across the street.”

As we enter the hotel’s somber lobby, Lourdes explains that this was Goa’s first “modern” building, commissioned in 1952 as a showcase for progress. Its elevator, a clattering affair with a cage door, was among the first lifts in this part of India. “It’s the exact same age as me,” she says as the antique contraption lurches upward.

The Riorico combines Rococo and Art Deco elements to amusing effect. There is a flowery, powder-blue-and-pink ceiling in the dining room, and a bar that transports you straight to colonialism’s fading days. A guitarist strums an old ballad in the background as we take our seats and order. Ten minutes later, a waiter with a red bow tie and an ill-fitting vest places the dish in question on our checkered tablecloth.

“In a Goan vindalho—the Catholic kind, mind you, and you better take care to spell it correctly—we use lots of garlic, pepper, turmeric, and cumin,” Lourdes tells me. “And we let the meat marinate for a day or two. This recipe should be kept outside before you eat it. How can you expect the taste to mature if it’s sitting in a fridge?” Again, I find myself nodding mechanically.

“Cooks these days,” she adds conspiratorially, arching her librarian’s brow, “they are starting to add tastemakers to the food—you know, those little monosodium cubes. And they’re changing the way of cooking. But this is just right, this vindalho. They may have even cooked it the day before yesterday.”

My taste buds concur. The vindalho is unlike any rendition of the dish I’ve eaten in countless Indian restaurants. Its taste is softer and rounder; tender chunks of pork shoulder fall apart under the pressure of a fork, and the garlic, turmeric, and chili are given a lift by the acidity of coconut- toddy vinegar, something Lourdes assures me “all good Goan cooks make at home.” Like the Mandovi River flowing just outside the window, the layers of spice come slow and easy.

The pace picks up later that afternoon, when I find myself sitting in a Maruti Gypsy driven by local musician and indie record producer Oliver Sean. The top is down, and American country music warbles out of the speakers above the sound of grinding gears. We round another bend and Miramar Beach flashes by, framed by bowed coconut palms under an egg-yolk sun.

“Goa is a lot like the American South,” Sean says, explaining the soundtrack. “It’s laid back.” So is he, with his mirrored Ray-Ban Aviator glasses and long curly locks blowing in the wind. I met Sean by chance on my first trip to Panaji two years before, and when I contacted him again on this visit he offered to show me around. Of course, I took him up on it. Who wouldn’t want to spend an afternoon with the local rock star?

We pull into a breezy roadside bar above Dona Paula Beach, on a hill overlooking the capital. We’re surrounded by vacation condos and other construction; Goa is fast becoming a holiday spot for nouveau-riche Indians.

“You should write about real Goans, about the real Goa,” Sean says with a hint of melancholy, “because it is disappearing. Goans are a minority in our own state now, outnumbered by immigrants from other parts of India.” We order a couple of Kingfishers and watch the sun slowly sink into the Arabian Sea. Then Sean decides to introduce me to a bit of the “real” Goa himself.

“Can we get some urak?” he asks the owner, who smiles and nods his head. “Make sure it’s fresh. I only want it if it’s fresh.”

Fifteen minutes later the man returns on his scooter, lifts the seat, and pulls out a plastic soda bottle full of clear liquid. Sean sniffs, nods, smiles. Urak—or arrack—is made from the fruit of cashew trees, which the Portuguese introduced to Goa from Brazil in the 1500s. It has a nutty, sour taste that is not unpleasant, but that goes down better when mixed with lime soda.

Sean and I sit and talk about his upcoming album and the success of his W.O.A Records label, about Bollywood and the Indian music scene, and about the languid, easy way of life in Goa that locals call sussegado. As the bottle empties, I realize I’m tipsy.

“In Goa, people think that if you drink urak indoors you won’t feel a thing, but if you’re outside and there’s a breeze, you’ll get very drunk.”

I chuckle. As if you need an excuse to sit outside in paradise.

For a town of less than 100,000 people, Panaji seems to have a lot of folks bent on preserving the past. Like Vasco Silviera, the tall, gruff proprietor of the Horse Shoe bar and restaurant. I meet Silviera in his kitchen—his staff walk me right in, unannounced—and talk to him about Goan cooking as he slices a kingfish into thick steaks.

Silviera is not from Goa. He’s an Angolan-born Portuguese, and he considers himself African rather than European. “Africa is a strange place; it gets in your blood and never goes away,” he says. In 1974, after the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon overthrew the Estado Novo regime and ushered in independence for Portugal’s African colonies, Silviera ended up in Europe, settling briefly in Germany. “Germany was too cold, and I hated the food there,” he recounts, frowning. “And there was too much political unrest in Portugal. So I moved to Goa in 1976 and never left.”

Silviera proceeds to whip me up a magnificent lunch. The highlight is sausage—small, rustic chouriços stuffed with a loose mix of meat and creamy fat that has been marinated in a zesty masala paste. They are salty, spicy, sour, and smoky: Iberian chorizo colored by the subcontinent. “These sausages are made by my butcher,” the chef tells me. “They are cured for 15 days above a wood fire, and taken out for one hour a day to dry under the morning sun.” Silviera savors the story as I savor the sausage, which I eat atop freshly baked bread.

That night, I borrow a scooter and drive to Panaji’s renowned Mum’s Kitchen, which lies on the fringes of town just before Miramar Beach. The atmosphere here is odd; with its adobe walls and hardwood furniture, it reminds me of the American Southwest. But I can’t argue with the menu, whose mission statement reads: “Mum’s Kitchen: Our move to save Goan cuisine.”

If you plan on retracing my steps, and of truly appreciating the substantial genius of Goan cooking, you might want to eat here first. Because Mum’s is a demystifying place, designed to ease the uninitiated into the curries and breads and dry-frys that typify this hybrid cuisine. The menu features concise descriptions of each dish. There’s a decent wine list. And most importantly, the food is genuine, not some half-baked concession to foreign palates.

Suzette Martins, the owner, comes to my table with a steaming plate of chicken cafreal, a basket of bread, and mushrooms in a spicy curry called xacuti. Then she explains what I am about to eat. Again, I find myself in the midst of a history lesson.

“Cafreal means ‘Africa’ in Portuguese, and this dish was probably taken from the colonies in Angola. But also, you will see some Brazilian influence here. To make my cafreal, I use a ginger and garlic paste, and a masala ground with fresh coriander, cumin, cloves, cinnamon, and black pepper. The chicken is marinated in lime juice, and then it is all brought together.”

That’s putting it modestly: Mum’s cafreal is much more than the sum of its parts. It’s not muddled or over-spiced, and each ingredient reveals itself slowly in the rich, green paste. I sop it all up with sannas, mildly sour bread made from fermented rice that is Goa’s answer to southern India’s idli.

Back in town, I park my scooter outside Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception. The church is lit up like a chandelier, but the rest of the town is dark. It’s 10:30. I stop for a nightcap in a run-down whiskey bar before heading off to bed. As I climb the hill toward my hotel, huge fruit bats flap by overhead, returning from a night of feasting in the trees.

My last day in Goa is spent on the road, heading south. I pass signs for yoga studios and vegetarian food, holistic centers and flexible gurus. Party flyers stapled to telephone poles announce the next European deejay to tour the beaches of Vagator, Arambol, or Candolim. Sun-burnished backpackers and old hippies whiz by on Vespas or growling Enfield motorcycles.

An hour later, just beyond the town of Margao, my driver turns off the main road into a quiet village. We pull up to a lush rise, and he lets me out in front of one of the pretttiest estates I’ve ever seen. This is the Palácio do Deão: home, restaurant, living museum, and labor of love. The mansion, painstakingly restored over a six-year period by Ruben and Celia Vasco da Gama, was built in 1787 by a Portuguese friar named Deão José Paulo, who was dean of the large church that faces the estate. His spirit lives on in the antique furniture, the long, haunting hallways, the chapel, and the terraced gardens he planted around the property.

“In Goa, the hinterland hides so many things,” Reuben says as he shows me his collection of old stamps and coins. “There is so much more here than beaches. We have Hindu temples, churches, lakes, forests. This little state is full of treasures that need to be saved—places like this.”

That afternoon, after touring the house, I sample Celia’s food. She too has re-created the past, in dishes that José Paulo himself might have eaten centuries ago. There are riossis—delicate, crisp bits of pastry filled with buttery prawns—and stuffed, baked crabs; tender squid and a tureen filled with a gentle, saffron-laced curry. It ends with a simple flourish: fresh red snapper, served with olive oil, salt, and slivers of garlic. It’s a perfect melding of Indian and European flavors—a meal that tells countless stories.

“People here are changing the way the dishes used to be cooked,” says Celia, joining me after my meal. “But I decided to cook things the old way. When things become threatened, I think they have a better chance of being truly preserved.”

THE DETAILS:

Panaji

Getting There

As there are no direct flights to Goa from Southeast Asia, much less the rest of the region, the state’s main international gateway tends to be Mumbai, from where Air India (airindia.com) and Jet Airways (jetairways.com) offer multiple flights to Dabolim Airport, 26 kilometers from Panaji.

When to Go

India’s west coast is humid and hot all year, and at its wettest from May to September. Skip the monsoon and aim for the cooler months of November to March instead.

Where to Stay

Just a short walk from Panaji’s town square, the four-room Panjim Peoples (E-212 31st January Rd.; 91-832/222-1122; panjiminn.com; doubles from US$112) occupies a former schoolhouse in the Fontainhas area. Rooms are palatial, filled with antiques that owner Ajid Sukhida collected on his travels across India.

Where to Eat

In the village of Quepem, about an hour’s drive south of Panaji, the Palácio do Deão (91-832/ 266-4029; palaciododeao.com) serves as a showcase for the cooking of Celia Vasco da Gama, whose classic dishes can be an enjoyed on a terrace overlooking the Kushavati River. Panaji is home to several not-to-be-missed restaurants. Make tracks to Viva Panjim (178 31st January Rd.; 91-832/224-2405) for a taste of Linda D’Souza’s tried-and-true recipes. For authentic vindalho, try Riorico (D.B. Marg; 91-832/242-6270) at the Hotel Mandovi, or grab a seat at the unassuming Horse Shoe (E-245 Rua de Ourem; 91-832/ 243-1788) and gorge on chouriço sausages and fish curries. Near Miramar Beach, Mum’s Kitchen (854 Martins Bldg., Panjim–Miramar Rd.; 91-832/246-5767) is dedicated to preserving traditional Goan cuisine; their chicken cafreal will make converts of us all.

Originally appeared in the February/March 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Goa On a Plate”)