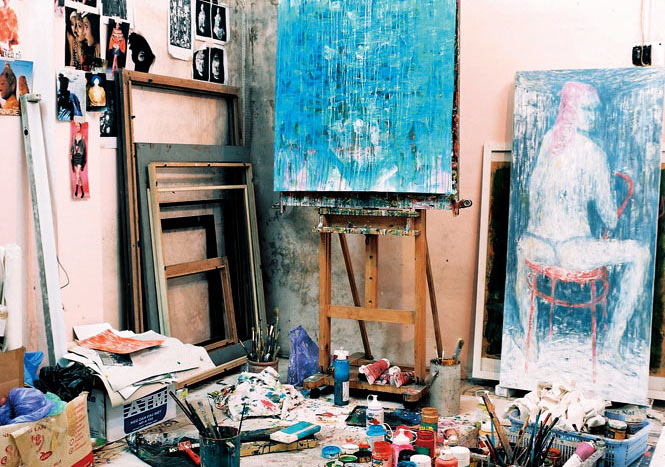

Above: The tiny studio of Ha Manh Thang.

Despite the ups and downs of the art market, Hanoi remains a vibrantly creative place

By Christopher Kremmer

Photographs by Jason Michael Lang

Only a rickety ladder connects to the attic above, where Hanoi artist Co Chu Pin awaits us. Below me, my Vietnamese friend Bui Minh Nguyet cranes her neck upward, smiling nervously, and tells me that nothing worthwhile is ever achieved without bravery.

“Keep going. His paintings are really good. You will enjoy them,” urges Nguyet, a respected art dealer and my guide to Hanoi’s creative scene for more than 15 years. So I keep going, and as my head emerges at floor level amid an oily mess of rags, palettes, and spent paint tubes, I’m suddenly transported.

There is something distinctly Parisian about this cramped loft under a Mansard roof, with small balconies looking across the rooftops of a 1,000-year-old city. From behind an easel, a face framed by a thick beard and tousled hair emerges. It’s Pin, lost in his work as usual.

Some artists paint nudes, but for this gnarled veteran of the artistic life, the city is his muse. I remember his work from the early 1990s, when I lived in Hanoi as a foreign correspondent for the Australian Broadcasting Commission. In those days—before doi moi (economic renovation) hit its stride—Pin’s canvases depicted a gray, slatternly capital of tangled power lines and streets lined by tumbledown houses desperately needing a fresh coat of paint. Now, color and light stream from doorways, and diners in lively curbside restaurants spill out onto the streets of his paintings, reflecting Hanoi’s rebirth as a city of charm and style. A city with a soul.

Not all is well as far as local artists are concerned, however. Pin was born in this house, and has lived his entire life on this street. But like Vietnam’s economy, Hanoi’s population has exploded, and the only way to go is up. New buildings sprout amid the old; needles of glass and concrete squeezed onto tiny lots. Pin, like others, worries about the threat to Hanoi’s ancient cityscape and culture. “I love old Hanoi, but it’s all slowly going,” he tells me, his eyes growing distant. “I want to capture it while it still exists.”

The economy may have opened up, but Hanoi still jealously guards its role as a fortress of Vietnamese culture, the dowager queen of Vietnamese cities. Sultry, capitalistic Ho Chi Minh City may be forever young, but Hanoi, crouched in the Red River Delta a few hours’ drive from the Chinese border, rules Vietnam culturally and politically. Which is why on this visit, I have chosen artists, rather than political analysts or tourist spruikers, to be my guides. While some have lost their way amid the economic boom, others look on with a cool detachment.

Today, a BMW sits parked in the driveway of Dang Xuan Hoa, who emerged in the 1980s at the vanguard of a new wave of Hanoi-based artists called the Gang of Five. They were the first postwar generation, and they seized the opportunities triggered by economic and social change to reconnect with the global art scene—and to create more than just pictures of heroic workers and peasants. Some, like Tran Luong, were boldly political; others, like Hoa, confined their rebellion to matters of style.

Hoa greets us at the door of his rambling, architect-designed home, a wiry, catlike figure with a trademark black goatee, padding barefoot across a broad expanse of polished stone floor. “Life is good. I can do what I want to do,” says the 53-year-old painter, whose work hangs in Hanoi’s Fine Arts Museum and is sold at auctions and galleries around the world. One painting can earn more than 10 times an average Vietnamese worker’s yearly salary.

Yet affluence seems not to have taken the edge off Hoa’s art. Some of his canvases are portraits of his own family. They look pensive, with quizzical expressions, their backs turned to each other. Their bodies are suspended by invisible forces, simultaneously beautiful and deformed.

“People in Vietnam are forever waiting. They’re worried, with many difficult decisions to make in order to achieve a good life. And there are still certain limits placed on us artists by government,” Hoa says. “But there is a new generation, and they have good conditions in which to make art. They try to experiment. I hope they do better than we did.”

The next morning I awake to the sound of church bells, at the aptly named Church Hotel near St. Joseph’s Cathedral on Nha Tho, the shortest but hippest street in Vietnam. My guide today is another of Hanoi’s most successful and knowledgeable art dealers, Pho Hong Long, who runs the Dong Phong Gallery. While a misty Orientalism pervades many galleries crowded with paintings of willowy Vietnamese maidens draped in silk tunics, Long is passionate about both Vietnam’s art greats—like 88-year-old Nguyen Tu Nghiem, a living legend—and rising stars of the new generation. But he also acknowledges that Vietnam’s art market has had its ups and downs, largely due to fakery. The boom peaked around 1997, with rampant copying and an oversupply of decorative art keeping prices low since then for all but top artists.

“There are three types of fake,” Long tells me, smiling incongruously. “First, are painters who impersonate the greats, copying their work and even their signatures to the last detail. Second, are those who copy the style of the masters and sign their own names. Some dealers encourage young artists to do this because the famous artist is not doing business with them. The third kind of forgery is the well-known painter who copies himself, reproducing the style that made him famous over and over again. He no longer develops as an artist.”

Steering clear of the rip-off galleries that crowd Hang Trong, Hang Hanh, and Nguyen Thai Hoc streets, Long takes me to the studios of new-generation artists Ha Manh Thang and Ly Tran Quynh Giang, both of whom cite Francis Bacon as an influence. We meet Thang, a native of Thai Nguyen province, in a tiny space filled with explosively colorful images of people and things.

Thang’s sculpted features and mischievous eyes are focused on the point where Vietnam’s ornate culture collides with Western capitalism. On giant Chinese scrolls he paints dazzling images of himself and his girlfriend seated on thrones and dressed in the robes of ancient Vietnamese royalty. But look closer and you notice that those exquisite robes are covered in Western designer labels like YSL and Gucci.

An artist since the age of 10, Thang rejected the classicism taught at the Hanoi University of Fine Art (founded under French rule in 1925) in favor of a vividly individualistic style. Like many of Hanoi’s top artists, he’s trying to articulate a response to the cultural and economic churning all around him. “I want to find a mix of Western and Oriental culture,” he says, coyly running a hand over his close-cropped scalp. “In this period you cannot look only at tradition, but you don’t want to lose it either.”

“He never repeats himself, that’s why I love his work,” chimes in Long. “He’s not copying himself or anybody for the market.” While Vietnamese artists today enjoy a more creative milieu, the government still maintains a share in most private galleries. Political artists like Le Quang Ha occasionally have their exhibitions shut down by cultural commissars who once adored gritty Socialist Realism, but now prefer happy capitalist art. Fortunately, 30 years of hard-line communism wasn’t enough to snuff out Vietnamese individuality.

The women painted by Ly Tran Quynh Giang glare defiantly at the viewer, obsessively frustrated and melancholy. It’s not a revolution, more an obstinate refusal to be uncritically cheerful in the new Vietnam. In her early thirties, Giang is cool but fragile. She still lives at her parents’ elegantly furnished home, whiling away the days smoking Camels, drinking endless pots of tea, and painting in a high-ceilinged room dominated by a huge ancestor altar. She began learning violin as a child, and the instrument often pops up in her work, a counterpoint in her nudes. When I asked this strident individualist what artists should do for their country, she answered in a voice soft as rustling leaves: “Just paint. Create a lot. Artists can only control themselves.”

Before leaving Hanoi, I wander over to Hoan Kiem Lake, whose placid, willow-lined waters are the tranquil eye in the storm of the city’s changes. In the narrow lanes nearby, people squat on low, plastic stools, hunched over bowls of steaming pho, the life of the pavements still an endless source of fascination for locals and visitors alike. People smile more than they did when I lived here, are better fed and better dressed. They may even be happier.

One thing is certain: there is nowhere else like Hanoi. What I learned on this visit is that its artists worry just as much about the threat posed by rampant capitalism to their city’s ancient culture and landscape, as they do about government restrictions on their freedom of expression. And yet the sounds and scents of the ancient alleyways are forever in their blood. This time, I realize, they are also in mine.

THE DETAILS:

Art in Hanoi

Galleries and Studios

Any art-minded visit to the Vietnamese capital should begin at the Fine Arts Museum (66 Nguyen Thai Hoc St.; 84-4/ 733-2131; vnfineartsmuseum.org.vn), whose extensive collection ranges from Champa-era artifacts to works by Gang of Five painters like Dang Xuan Hoa. For a well-curated survey of Hanoi’s avant-garde scene, visit Art Vietnam Gallery (7 Nguyen Khac Nhu St.; 84-4/ 927-2349; artvietnamgallery.com), where American Suzanne Lecht has turned a two-story French villa into a showcase for contemporary photography, painting, and sculpture. The smaller Suffusive Art Gallery (2B Bao Khan Lane; 84-4/ 828-8359; suffusiveart.com) is also worth a look for its stable of young Vietnamese talent.

Better yet, meet the artists at their studios. Hanoi’s dealers are constantly roaming the city, seeking work by established and new artists for their galleries, and will be happy to take you along. Pho Hong Long is as good a guide as any; to arrange studio visits with artists like Ha Manh Thang and Ly Tran Quynh Giang, contact him at his Dong Phong Gallery (21 Trang Tien St.; 84-4/3936-0481; dongphonggallery.com).

Originally appeared in the August/September 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Character Study”)