Above: Trekking a treeless ridge.

A former Gurkha officer takes trekking enthusiasts off the beaten path in Nepal.

Story and photographs by Jonny Beardsall

Even hailstones the size of golf balls fail to disrupt our boozy game of bridge—though the fact that we’re in a tent on a boulder-strewn ridge, 3,810 meters up in the Nepalese Himalayas, causes a few of us to raise our eyebrows. Christopher Ussher, a former British Gurkha officer and our guide on this excursion, is quick to offer reassurances. “Don’t worry. The boys will hang on to the guy ropes. Would anyone like a top up?”

Ussher, a tough fiftysomething from northern England, has been leading small groups of hikers through this part of the world for more than 20 years. We’re at the end of the first day of a six-day trek through Langtang National Park in the shadow of the Jugal Himal, northeast of Kathmandu. Hemmed by soaring peaks, including the 7,246-meter summit of Langtang Lirung, the region is still relatively isolated, despite being only 70 kilometers from the Nepali capital. It’s a place where the weather can change without warning. Still, despite the storm outside our canvas, we’re remarkably comfortable, thanks to Ussher and his team.

Our camp begins to take shape just before dusk. Ussher’s crew of 45 porters unload their heavy baskets, and guides and cooks rush over to help unpack. A flurry of snow muffles their voices as they swiftly set up tents, tables, and cooking equipment. Bedrolls are laid out, fires are lit.

Our sleeping quarters are spacious, with four people to a tent. And there are other unexpected luxuries, including hot showers in the afternoons and a delicious shepherd’s pie from the camp kitchen. At bedtime, we’re given hot water bottles to keep our feet warm through the night. Even the portable outdoor toilet comes with a frill: a wooden seat. I wonder if the great 19th-century plant-hunting expeditions of botanists like Frank Kingdon-Ward were so well equipped.

“We offer a high degree of service when on trek, and to do so we employ a great many people, which is a good thing, given that this is one of the world’s poorest countries,” Ussher tells me over a steaming mug of lemon tea.

Although trekking expeditions are growing in popularity across the country today, this is an experience that was off limits to tourists for the first half of the 20th century. Nepal, then a closed country, was a kingdom in name but ruled in fact by the ultraconservative Rana family. In 1951, Nepal’s titular monarch, King Tribhuvan, invaded his own land with an army, ending Rana hegemony and opening Nepal—and its peaks—to outsiders. Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers to summit Mount Everest two years later, and a trickle of foreign mountaineers followed.

Trekking—as opposed to mountain climbing—only really started to take off in the 1960s when Colonel Jimmy Roberts, a former Gurkha officer and military attaché at the British Embassy in Kathmandu, began leading tours around Nepal’s peaks. In 1965, Roberts established a trekking company called Mountain Travel, the first of its kind in Nepal, employing local porters to carry tents and equipment in an expedition style that Ussher and other tour leaders continue today.

Drinking more lemon tea around the campfire, Ussher tells me how he first came to Nepal in 1978. As a young officer, he was charged with walking the hills and paying pensions to retired Gurkha soldiers in east Nepal. At the time, he recalls, there were few tourists trekking in the country’s remote regions, most of them preferring the well-trodden trail to Everest Base Camp. “I figured that a lot more people would come if they could go off the beaten track,” Ussher says. “This is what I started doing when I left the army in 1983. I’d say I’d got it right five years later when I led a group of 15 lawyers and their wives. That was when the business really took off.”

We wake on day two to find the ground blanketed with an inch of snow. Hot drinks are brought to us while we’re still in our sleeping bags, followed by a breakfast of porridge and scrambled eggs with sausages, beans, and toast, which we enjoy at a long trestle table set up in the open. As the mist rises, the beauty of our surrounds begins to unfold. A range of snowy peaks looms over us, dotted with Buddhist chorten decorated with sun-bleached prayer flags. Below us, a deep valley falls away to forest and terraces of rice, potatoes, and maize. I hear a bird twittering in the distance. “Have you spotted it?” asks Ussher, who recognizes the call as being that of a black-faced laughing thrush.

Our trek began in Chautara, a small, windswept town set at an altitude of 1,450 meters. Most expeditions from here last 11 nights, taking hikers to Panch Pokhari, an area encompassing five sacred lakes in the heart of the national park. We’d planned a more leisurely itinerary: over the next six days we’d cover around 60 kilometers, giving us plenty of time to acclimatize and enjoy our surroundings.

The landscape changes dramatically as we begin our ascent. By the afternoon of day two, we’ve moved from a warm, green valley to dense alpine forest: massive rhododendron trees with twisting dark brown limbs interspersed with towering hemlock, silver fir, and prickly oak. It’s spring, and the rhododendrons are in full bloom, staining the mountainside every shade of pink imaginable. At our feet we find pretty alpine wildflowers like primula carpeting the ground with particolored blossoms.

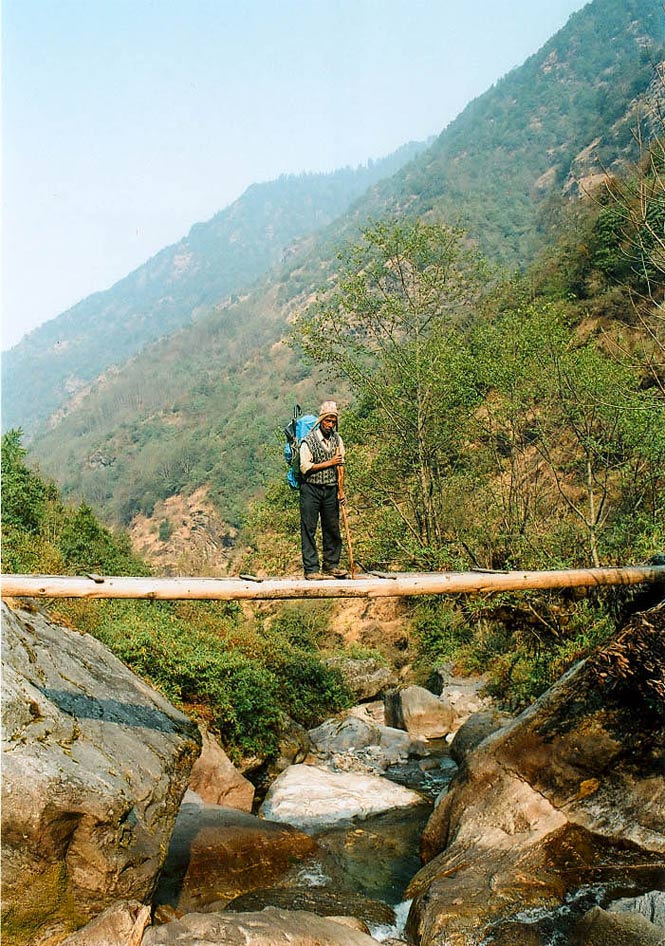

Above, from left: A trail leads through a rhododendron forest; a log bridge at Bhareng; rhododendron blossoms; Christopher Ussher taking in the scenery.

Taking a gentle pace, we walk for no more than six hours each day. Ussher keeps us company, but our porters—Tamangs and Bahuns from these very hills—push ahead, giving them time to set up for morning tea and lunch as well as our evening camps. Unable to keep meat fresh while on the move, they buy live chickens from villages along the way, tying them to their backpacks with pieces of twine.

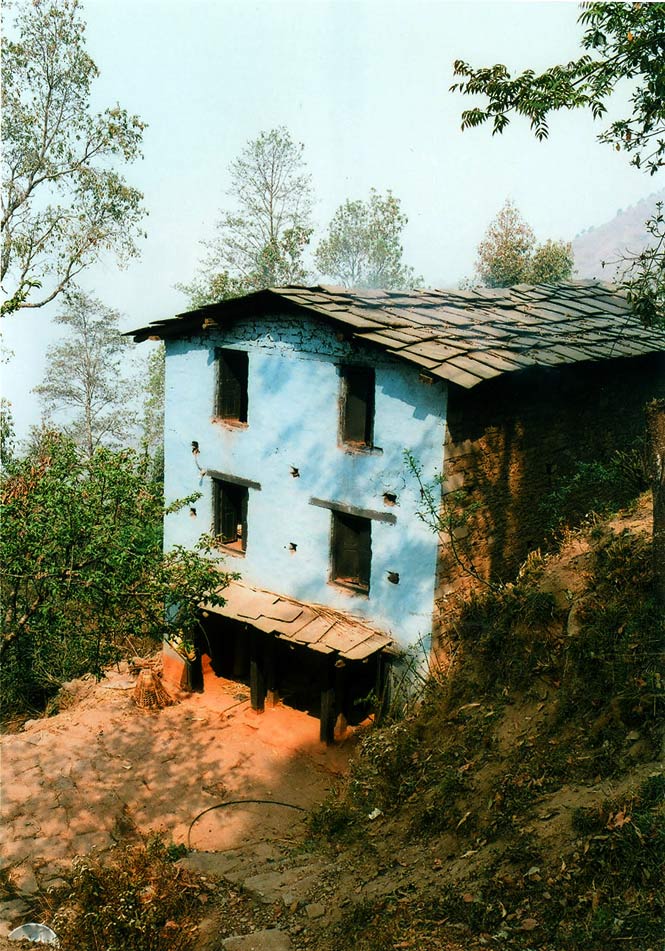

We pass small, simple villages made up of two-story houses of mud and stone. Buffalo and rheumy-eyed cows gaze back at us from stalls on the ground floor of the homes. We notice that some walls are still covered with hammer-and-sickle campaign posters. In 2008, the country’s Maoist party swept to victory, with much of their support coming from Nepal’s rural residents. “They promised much to these people,” Ussher laments, “but haven’t delivered.”

The locals we meet are mostly at work in the fields. Life here seems to proceed as swiftly as we walk, which is to say, not very fast. We see a farmer tending to a tiny patch of soil with a plow pulled by two buffaloes. His wife walks behind, sewing maize in the furrow. Farther on at a streamside watermill, we watch millet being pulverized into flour on a grindstone. Children in sun-bleached uniforms stop to talk to us on their way to school. In a house opposite, a man sits at a foot-operated sewing machine, making running repairs to a weary blanket.

We meet few other trekkers on our trip; Ussher tells us that paths are busier in the warmer months. There are more tourists in summer, and the trails also become filled with locals come autumn as herders move animals to higher slopes after the monsoon rains, and pilgrims make their way to the holy lakes at Panch Pokhari, a two-day walk from Malamchi Pul Bazaar where our journey ends.

“When they get to Panch Pokhari, they make offerings of rice to Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction,” Ussher says. I tell him that seems like an unlikely deity to be worshipping in such a beautiful part of the world. He grins, and pulls up the collar of his fleece jacket. “This place gets under your skin, alright. I never tire of coming here.”

A six-day trek through Langtang National Park with Ussher Tours (usshertours.com) costs US$3,740 and includes four nights’ accommodation in Kathmandu and two nights in Chitwan National Park.

Originally appeared in the February/March 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine ( “Himalayan Highs”)