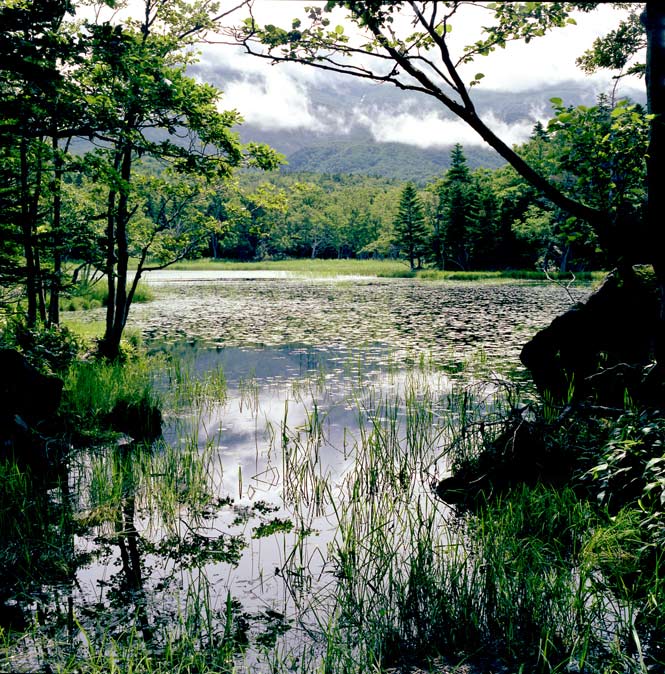

Above: A boardwalk at Shiretoko Five Lakes.

Hokkaido’s untamed Shiretoko Peninsula conceals some of the wildest places in Japan.

By Mark Brazil

Photographs by James Whitlow Delano

Close your eyes and think of Japan. What do you see? Is it the neon glow of Tokyo’s bustling cityscape? Or perhaps the hushed temples and immaculately manicured gardens of Kyoto and Nara? These are all fine images. But if you could cast your mind’s eye to Hokkaido, second-largest and northernmost of the Japanese islands, you would be envisioning a very different place: a land of forest-clad volcanoes, of brown bears and sea eagles, and of vast, wide-open spaces. Hokkaido is Japan’s last frontier, its Wild West, home to seven national parks and only 5.6 million inhabitants—about four percent of the country’s entire population. And nowhere is the island’s untamed beauty more enthralling than at its northeast extremity, Shiretoko, a rugged peninsula that juts like an admonishing finger into the Sea of Okhotsk.

I have lived in Hokkaido for many years, on the outskirts of Sapporo, the island’s prefectural capital. Shiretoko beckons regularly to the naturalist in me. My latest trip begins, as usual, in the east-coast city of Kushiro, a four-hour train ride or short flight from Sapporo. From there, I drive northward through Kushiro Shitsugen National Park, an enormous preserve of lowland marsh and undulating wooded hills that is home to rare whooper swans and the magnificent red-crowned crane. The wetlands soon give way to the montane scenery of Akan National Park. At the town of Teshikaga, I wrestle with serious temptation. Framed against the deep-blue sky, the majestic volcanic peaks of Me-Akan and O-Akan loom enticingly to the west, while to the northeast, the rim of Hokkaido’s most beautiful crater lake, Mashu-dake, exerts a pull of its own.

Flanked by forests of mature spruce, fir, birch, and oak, the wide road I’m on, Route 391, bypasses the hot-spring town of Kawayu before winding up toward Nogami Pass. Behind me now and to the southwest, Lake Kussharo—at 26 kilometers in diameter, it is Japan’s largest caldera—shimmers in the summer sun like an immense mirror. After cresting the pass, the road carries me rapidly downhill again, a rushing brook providing musical accompaniment for part of the way. As I descend from the forested mountains onto the Konsen Plateau, a great checkerboard of farmland stretches out before me, crisscrossed by a grid of larch shelterbelts that is so extensive it can be seen from space (as Japanese astronaut Mamoru Mori, aboard the space shuttle Endeavour, famously discovered a decade ago). In winter, I have watched the island’s nimble red foxes hunting voles here, but today, the fields—planted mostly with potatoes and sugar beet—are thick with the coming harvest, and the only wildlife I see are the skylarks singing above them.

The wide-open spaces of rural Hokkaido are enthralling, but already I can see peaks ahead, outliers of the range of mountains that forms the spine of the Shiretoko Peninsula, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2005. The dramatically isolated summit of Mount Shari, 1,545 meters high, dominates the skyline at first, joined soon by the main range and the towering cone of Mount Rausu. They are a splendid and welcoming sight, their flanks lush and green, their gullies still powdered with lingering snow.

This lofty peninsula of mountain valleys, stratovolcanoes, and sea cliffs is 25 kilometers across at its widest, and protrudes almost three times that distance from the Hokkaido mainland. It takes its evocative name, which means “the end of the earth” in the language of the Ainu, from a people one is hard put to meet. The indigenous inhabitants of Japan are likely related to ethnic groups that originally populated Siberia. As Japan’s mainstream Yamato culture spread northward over the centuries, the lighter-skinned Ainu, a society of hunters and gatherers, retreated to the fastness of Hokkaido. It proved a short-lived sanctuary. With the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese government opened Hokkaido to colonization, forcing the Ainu to assimilate. They became an invisible minority, overwhelmed by waves of Japanese settlers, their lands “redistributed” and their language and animist beliefs banned. When, in 2008, Japan’s parliament belatedly recognized the Ainu as “an indigenous people with a distinct language, religion, and culture,” it was all but too late. The Ainu population in Hokkaido today numbers perhaps 16,000 and few, if any, are full-blooded Ainu. You can still visit their villages, like the one at Lake Akan, but these are reconstructions built for tourists, and hardly worthy of a once proud people.

At Shari on the north coast, I follow Route 334 past the broad, rushing falls known as Oshinkoshin and as far as Utoro, a small seaside town with limited intrinsic appeal save for its hotels, seafood, and onsen hot-spring baths. This is the main gateway to Shiretoko National Park, a 386-square-kilometer reserve that occupies almost half of the peninsula and receives roughly three million visitors a year. A good share of them visit the famous Shiretoko Five Lakes, which is just 20 minutes up the road from Utoro. It’s a beautiful setting, surrounded by carpets of wildflowers. But when I arrive, busloads of Japanese tourists, with their uniformed, flag-waving, and whistle-blowing guides, are already overrunning the boardwalks. Were I behind the wheel of a four-wheel-drive, I would continue along the narrow, limited-access road that leads northeast from the lakes and turns into a dirt track before ending at a cluster of old fishing huts. I remember traveling along this track one autumn morning with some colleagues from Sapporo. The jeep we were in skidded on some frost, taking us perilously close to the edge of a hundred-meter drop to a boulder-strewn beach. The wild scenery—crashing waves, a procession of dramatic headlands—remains etched by adrenalin into my memory to this day.

Backtracking a little toward Utoro, I rejoin Route 334 as it snakes its way inland, up and over the spine of the peninsula. Massive gates close this road from November to April each year, but it opens for the warmer months. Arrive at the 740-meter Shiretoko Pass before dawn on a clear summer’s morning, and you can watch the sunrise from behind the silhouetted shape of Russia’s Kunashir Island, southernmost of the disputed Kuril chain. If fog isn’t blanketing the coast, you can also watch intrepid motorcyclists fly around the curves of the road as it descends toward the small fishing port of Rausu, on the peninsula’s eastern shore.

It is summer now, lush and green, but when I was last here it was winter and the weather was raw and tempestuous, the landscape obliterated by swirling clouds of storm-blown snow. At such times, this truly does feel like the end of the earth. The seasonal contrast is almost unimaginable. In late spring, wildflowers abound and the snow’s whiteness is replaced by the creamy perfection of giant water plantains and trilliums. During the brief, vibrant flourish of summer, emerald green becomes the dominant hue, broken here and there by the orange of tall lilly spikes and the pinks of wild roses. In the open areas where dwarf bamboo and the huge-leaved Japanese butterbur thrive, sika deer can often be seen foraging. Shiretoko’s full palette of color takes over as the splendor of autumn pours down the wooded hillsides like an overflowing paint box. In from the sea come salmon, thronging the river mouths, surging upstream to spawn. As autumn’s rush fades again into winter’s bleakness, the eagles come, too. Not just any eagles, but arguably the world’s largest and most spectacular: Steller’s sea eagle, named after the 18th-century naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, who sailed on Vitus Bering’s ill-fated voyage across the northern Pacific. They migrate from their breeding grounds along the coasts of Kamchatka and Okhotsk, and gather here to feed along the edge of the sea ice.

The best, and easiest, way of enjoying this astonishing wealth of nature is from the sea; the peninsula’s scale is such that a little distance provides sufficient perspective to take it all in. During summer, one can go out from the harbor at Utoro by boat, either partway along the peninsula or as far as its very tip. You’ll pass Kamuiwakka Falls, where the spume of scalding, sulfurous water stains the sea a yellowish-brown. You’ll take in great jutting outcrops with names like Tako-iwa (Octopus Rock) and Shishi-iwa (Boar Rock). And, if you make it all the way to Cape Shiretoko, you’ll see rugged, crag-buttressed cliffs and clamorous colonies of cormorants and spectacled guillemots. Tourist boats venture out of Rausu, too, heading farther offshore to watch marine life (Dall’s porpoise, orca, minke and sperm whale, and Steller’s sea lion are all possible sightings in their season), or cruise closer in, for the chance to see Japan’s largest land mammal—the brown bear—roaming the coasts at a safe distance.

Rausu, whose fishermen harvest pollock, salmon, sea urchins, and the thick, leathery kelp known as konbu, is not quite the end of the road. That honor falls to the even smaller community of Aidomari, just up Route 87. But there, the tarmac stops. The last 20 kilometers of the peninsula remain completely isolated, accessible only on foot (for the very tough) or by boat.

In any season, at the end of a long day of hiking or driving, there is only one thing to do to ease away any aches, and that is to relax at an onsen. Rausu has several options for this, of which my favorite is Kuma-no-yu (“Hot Water of the Bears”). Tucked into the hills behind town, it is flanked on one side by a river, with old wooden changing rooms and separate bathing pools for men and women. The water is hot—so hot that I can only spend a few minutes immersed in it. But that is balm enough for my road-weary muscles, and the perfect end to a day in Japan’s great outdoors.

Dr. Mark Brazil, a long-term resident of Japan, is a lecturer, traveler, naturalist, and author. His latest book is Field Guide to the Birds of East Asia (A&C Black, 2009).

THE DETAILS:

Shiretoko

Getting There

Sapporo’s New Chitose Airport is Hokkaido’s largest and is served by flights from Tokyo and other Asian cities, including Taipei and Seoul. From Sapporo, one can fly to Kushiro City or Nemuro, and proceed to the Shiretoko Peninsula by rental car, bus, or with a guided tour. There’s also a regular train service between Sapporo and Shari.

When to Go

While summer (June to early September) is considered the best time to visit Hokkaido, the snow-clad scenery of winter can also be spectacular, though much of Shiretoko National Park is closed then.

Where to Stay

Just beyond Rausu, the charming Rausukuru Resort Inn (81-153/892-036; doubles from US$192, half board) occupies a Canadian-style log house, with seven tatami rooms and five Western-style rooms. In Utoro, your best bet is the Ikura Hotel (81-152/242-888; iruka-hotel.com; doubles from US$ 212, half board). It won’t win any design awards, but the hotel has some English-speaking staff and all 13 of its rooms look out over the ocean.

Originally appeared in the August/September 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“The End of the Earth”)