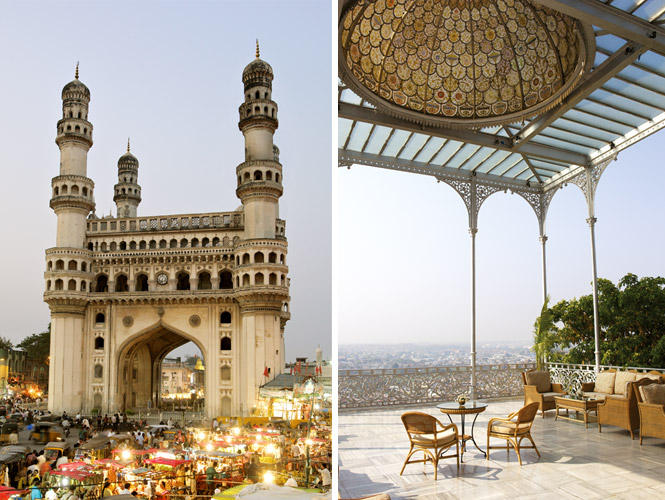

Above: the Charminar; a view from Taj Falaknuma Palace.

Once the seat of India’s richest princely state, Hyderabad is booming again as a high-tech hub of the country’s software industry. It’s a city whose bright future has yet to outshine its illustrious past, and where the echoes of nizams and nawabs still resound among resurrected palaces and grand monuments

By Shoba Narayan

Photographs by Srinivas Chandalla

“What would Madam like? Burka or miniskirt?” asks a boy of about 10 as he trails me through Laad Bazaar, a kilometer-long stretch of shops and stalls leading to Hyderabad’s Charminar mosque. On one side of the street hang patterned headscarves, burkas, and other chaste Islamic raiment. On the other is what my young tout calls “bling-mania”: a riotous display of diaphanous candy-pink skirts and low-cut sequined tops in the style favored by Bollywood heroines.

“This particular miniskirt is just like the one Bipasha Basu wore in Dhoom 2,” says the boy, referring to the Hindi heist caper that led the Indian box office in 2006. “College girls love it. And Madam,” he adds, assessing me with a precocious eye, “has the shape for it.”

Oh, he’s good. But I haven’t come to the heart of old Hyderabad for skirts, or bangles, or any of the other myriad items—henna, kohl, pearl jewelry—for which Laad Bazaar is renowned. What I am looking for is romance —an epic romance, really.

In the late 16th century, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, a poet-prince of aquiline features and Persian descent whose portrait now hangs in the Smithsonian, fell in love with and married a Hindu nautch girl called Bhagmati. When, as a young sultan, he moved his court from the fortress town of Golconda (now a picturesque ruin on the outskirts of Hyderabad) to the more salubrious banks of the Musi River in 1591, he named his new capital after his beloved, who was given the title Hyder Mahal upon her conversion to Islam.

“Hyderabad is a city born from love,” says Jayanti Rajagopalan, owner of a bespoke tour company called Detours. “Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal, but Quli Qutb Shah built an entire city for the woman he loved!” We are sitting at Farasha, a venerable Iranian café in the shadow of the Charminar’s fluted minarets. Outside, motorbikes and auto-rickshaws whirl around the 400-year-old monument, a masterpiece of Indo-Islamic architecture that looks vaguely like a turreted Arc de Triomphe. College girls stroll by in tight jeans and T-shirts. Burka-clad women clutch children sucking on neon-green popsicles. Everywhere, there is the din of commerce, as people haggle over produce, trinkets, and Unani medicine that promises to give “strength” at night. But it’s not all business. Across the street from the Charminar, 10,000 of the faithful can worship together at Makkah Masjid, among the grandest and most revered mosques in India. Its central arch, Jayanti tells me, is embedded with bricks made from soil brought back from the holy city of Mecca.

Modeled on the Persian city of Esfahan, Hyderabad was originally designed around gardens, fountains, palaces, public baths, and reservoirs for moon gazing. At its center was the Charminar, presiding over the junction of four cardinal roads. The surrounding bazaars were rich in gold, diamonds, and the luminous gems that earned Hyderabad the nickname “City of Pearls.” The area still serves as one of the country’s most colorful marketplaces. Along Laad Bazaar, stacks of lac-and-rhinestone bangles glitter like compressed stars in mirrored display cases. In the back are the workshops, where bare-torsoed men heat the lac over coals, beat it flat, and shape it into delicate circles. While the lac is still warm, jewelers with nimble fingers press rhinestones into the bangles. Butterflies, flowers, and even the Taj Mahal are used as motifs. The designs remind me of Judith Leiber handbags.

As befits a city located pretty much at the crossroads of the country, Hyderabad, the state capital of Andhra Pradesh, is a confluence of Indian cultures. Its six-million-strong population is equal parts Hindu and Muslim. People here tend to be more flamboyant than their reserved southern neighbors, and have an easier relationship with wealth than, say, frugal Karnatakans. Women bejewel themselves with uncut diamonds and sequined saris, while men dress in smart sherwanis, which Jawaharlal Nehru adapted and popularized as the Nehru jacket. As for Hyderabadi weddings, they can be every bit as over-the-top as Punjabi ones.

On the other hand, the city is more conservative than those of the north, with a tradition of courtly manners and elaborate courtesies that can be either stultifying or refreshing, depending on your perspective. Nor do Hyderabadis share Mumbaikars’ reputation as freewheeling traders, impatient to close a deal or transaction. For all that their city has emerged as a high-tech boomtown, life here has an unhurried quality. Hyderabadis take time to anoint themselves with attar perfume, and think nothing of waiting in line to enjoy the famed biryani at Paradise Restaurant.

“Despite being the sixth-largest and wealthiest city in India, Hyderabad is a pretty laid-back place,” says Gulzar Natarajan, a young bureaucrat from the tony suburb of Banjara Hills. “And Hyderabadis are extraordinarily helpful. If your car is going to break down at night somewhere in India, this is where you’d want to be. People will take you in and take care of you.” And where else, I wonder, can one so easily rub shoulders with royalty?

I meet Begum Saleha Sultan for lunch at the beautifully restored Chowmahalla Palace, former seat of the nizams of the Asaf Jahi dynasty, who ruled Hyderabad—then a principality about the size of Italy—from 1724 until its annexation by India in 1948. Dressed in Indian silk with Bulgari earrings and Versace glasses, the 70-year-old princess cuts a dignified figure. Her husband is Bashir Yar Jung of yderabad’s Paigah family, a noble clan once almost as powerful as the nizams. She is also a close friend of the Turkish princess Esra Jah, former first wife of the current nizam—“more like a sidekick really”—who a decade ago took charge of rehabilitating both the Chowmahalla and Falaknuma palaces.

After finishing our chilled watermelon juice, flatbreads, and a kaleidoscope of curries, Princess Saleha introduces me to a young Austrian cabinetmaker named Zeigfried (“just call me Ziggy”), who has been helping to refurbish the Chowmahalla’s woodwork for seven years. He takes me on a tour of the complex, which now serves as a public museum.

Dating from 1751, the Chowmahalla was modeled on the shah’s palace in Tehran; its four wings border a central courtyard with a rectangular pond and fountains. Meticulously restored court costumes, each bejeweled with sequins on silk, are laid out in one wing. Opposite them is the library, where a team of Urdu and Persian scholars works at cataloging and organizing the estate’s huge collection of Islamic manuscripts. The palace’s crowning glory is the Durbar Hall, a vast, marble-floored reception room with arched pillars, ornate stuccowork, and glittering chandeliers. It was designed to impress the most regal of guests, and, after years of neglect, it’s doing so again today.

Last year, Princess Esra’s restoration of the Chowmahalla received a UNESCO award for cultural heritage preservation. Yet for all its grandeur, the palace today only hints at its former magnificence, when it was staffed by 7,000 retainers (several of whom were employed solely to crack the royal walnuts) and considered one of the finest royal residences in the country. But the good times were not to last. When British rule ended in India 64 years continued on pg. 104 ago, the seventh nizam of Hyderabad, Sir Osman Ali Khan, refused to join the new Indian union. Mohammed Ali Jinnah came down from Pakistan to try to persuade Hyderabad to accede to Pakistan instead. “But Jinnah lit a cigarette in front of the nizam and that put an end to all discussions,” recounts Bashir Yar Jung.

An eccentric whose personal fortune was estimated by Time magazine at US$2 billion in 1937, making him among the richest men in the world, Sir Osman was unable to hang on to the semi-independence he had enjoyed during the Raj. The Indian army invaded in 1948, in a campaign dubbed Operation Polo because of the state’s extravagant number of polo grounds—17 in all. After five days of fighting, Sir Osman capitulated. The nizam’s title was officially abolished, and Hyderabad was eventually carved up between Maharashtra, Karnataka, and the newly formed state of Andhra Pradesh.

When Sir Osman died in 1967, his 33-year-old grandson and successor, Mukarram Jah, inherited an estate saddled with debts and litigation. Six years later, with many of his assets frozen in Indian courts and his marriage to Esra ending, he fled to Western Australia to take up sheep farming. When creditors came knocking on the door, he was obliged to relocate again, this time retiring in Turkey.

In Jah’s absence, his neglected palaces fell to ruin. The Chowmahalla was plundered and parceled off; of the estate’s original 18 hectares, less than six remain today. Then, after a 30-year absence, Princess Esra unexpectedly appeared on the scene. She had, according to family accounts, reconciled with her ex-husband at their son’s wedding in London. Jah gave her carte blanche to salvage whatever remained of their children’s inheritance. Esra hired a lawyer, negotiated the release and sale of contested assets, paid off debts and settled legal disputes, and used what was left to rescue the Chowmahalla.

Esra also oversaw the restoration of the Falaknuma Palace, which is set on a hilltop south of town. Ten years ago, it was bolted up. Giant cobwebs hung from the ceiling and its great halls were falling apart. Reopened as the Taj Falaknuma Palace hotel late last year, it is one of India’s great conservation success stories.

Built by Sir Vicar ul-Umra, a Paigah emir then serving as Hyderabad’s prime minister, the Falaknuma (“Mirror of the Sky”) is a baroque amalgam of European architectural styles—Italianate in parts, Victorian in others, with Tudor and French Renaissance touches thrown in for good measure. It took Sir Vicar seven years—and most of his fortune—to construct. He would keep it for little more than a decade.

Over dinner at the hotel. Faiz Khan, the emir’s great grandson, tells me that in the spring of 1897, the palace received word that the sixth nizam, Mahboob Ali Pasha, was coming to visit his sister, Sir Vicar’s wife.

“Sir Vicar thought that the nizam would come for tea and leave the same evening. But he stayed for close to a month,” Khan says. “So Sir Vicar ended up giving up the palace as nasr [offering] to the nizam. Three generations of his family moved out the same evening. You know, parting with something so beautiful, so substantial, it must have been very painful.”

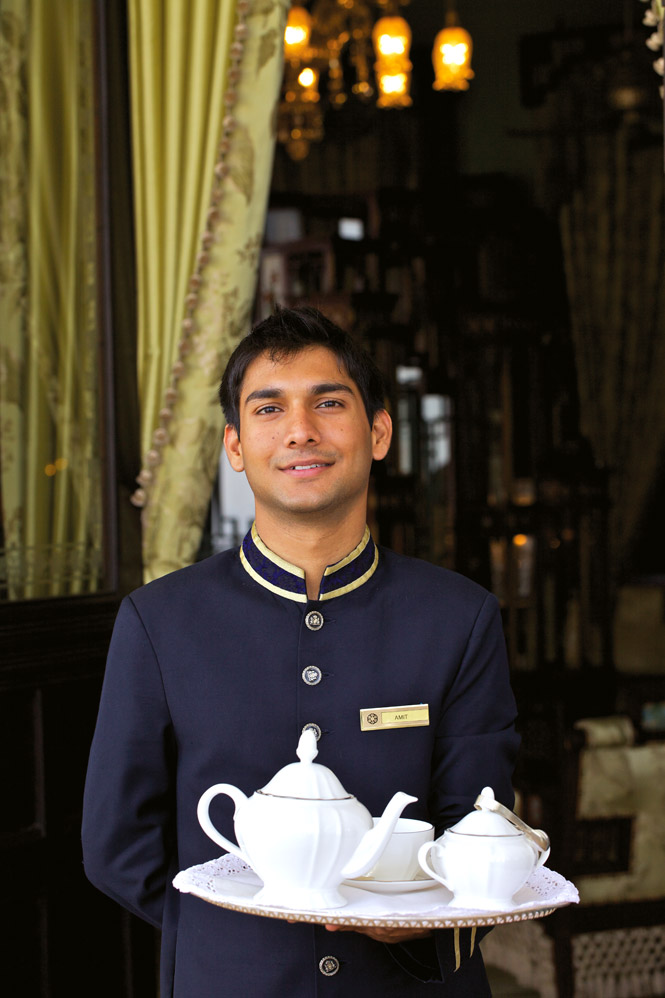

Today, the Taj group has retained the palace’s essence with some of its own luxurious additions. Its staff glide quietly through the pristine white corridors; the suites in the former zenana (women’s quarters) are accessorized with distinctive stationary, fragrant toiletries, and ridiculously soft bed linens. Lawn sprinklers throw off a million rainbows in the morning in a bid to counter Hyderabad’s arid January weather. The Jiva spa offers soothing aroma massages using organic ingredients. Guests are welcomed by a horse-drawn carriage (complete with liveried coachman) that carries them to the main lobby, where, atop a stunning cantilevered wooden staircase, hang portraits of Paigah nobles. Among them is Sir Vicar, a bearded man with soulful eyes.

Sir Vicar’s remains rest in the stunning Paigah Tombs, tucked away in the quiet neighborhood of Saidabad. Few tourists come here. I spend a quiet hour wandering among the mausoleums of successive Paigah nawabs and their wives, each surrounded by intricate jali lattices, floral and fruit motifs, and Rajput flourishes.

The whole effect is serene yet powerful a far cry from the ostentatious Falaknuma. Then again, the palace was Sir Vicar’s display to the world, while the tombs offered succor to his soul.

If the Taj Falaknuma Palace epitomizes old Hyderabad, then another new hotel conveniently symbolizes all that is modern. Overlooking Hussain Sagar Lake and its towering Buddha statue, the Park Hyderabad rises from its downtown plot like an angular spaceship, with 270 sleekly outfitted rooms, a restaurant crafted by Mumbai fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani, and a nightclub one accesses via a translucent tube that passes through the swimming pool. Its computer-modeled facade is meant to recall the delicate metalwork of nizami jewelry. But everything else about the place speaks to a younger, shinier, more upwardly mobile Hyderabad, with its world-class Indian School of Business, its prolific Telugu-language film industry, and its sprawling IT corridor, nicknamed Cyberabad, whose tenants include Google, Microsoft, Dell, and Motorola.

Hyderabad today is at a crossroads, at once racing toward a gilded future while trying to retain its storied past. “Hyderabad has a rich cultural legacy, but it’s being forgotten,” says jewelry designer Suhani Pittie, who lives in a 200-year-old mansion in the heart of the old city. “Today’s youngsters care more about bars and brands than they do our architecture and arts. They’ve lost touch with their past.”

Certainly, the party scene at the Park Hyderabad seems firmly focused on the present. On Saturday night, the hotel’s prism-like Carbon Bar is hopping with twentysomethings—young studs in tight jeans and preening girls in little black dresses, all downing martinis and nibbling on tandoori prawns. I strike up a conversation with some budding entrepreneurs. They talk about Hyderabad as if it were in the throes of a gold rush. “There is so much cash in this city,” says one. “It’s just like during the time of the nizams. People are spending money like water.”

Not always their own money, mind you. In the last couple of years, Hyderabad has been rocked by business scandals, notably that of Satyam Computer Services, which cooked its books on such a scale that it was labeled the Enron of India. There has been political tension too, in the form of a long-standing movement to separate the Telengana region, where Hyderabad is located, from coastal Andhra Pradesh. Last March, a rally led by thousands of pro-Telengana agitators shut down central Hyderabad for a day.

Akbar Ali Baig, a miniaturist who lives in the old part of town, talks desultorily about how the city has changed over the years. “Telengana or Andhra? Hindu or Muslim? When I was young, we didn’t care,” he says, gesturing absently out the window of his studio to where bright green parakeets sing in a mango tree. “Hyderabad was modeled on Jannat [heaven]. It is a city made for romance and royalty.”

Baig specializes in painting Hindu gods and goddesses; miniature canvases are stacked against the walls. With pride, he tells me that one of the nizam’s sons bought one of his works. And he talks of hours spent at the vast Salar Jung Museum, studying the techniques of past masters.

The Salar Jung claims to be home to the world’s largest one-man art collection, with an eclectic assemblage that ranges from antique European clocks to rare Koranic manuscripts. However, the richness of Hyderabadi arts and crafts lies not in the museums, but in its small textile workshops.

Suraiya Hasan Bose is the most energetic 81-year-old I’ve ever met. She teaches widows to weave saris and shawls from delicate fabrics that were introduced to India from Persia. It is painstaking work. The intricate paisley and floral designs can take weeks to finish. Next door, kids race around the free school that Bose runs for underprivileged children.

Bose is credited for her almost single-handed revivals of himroo (Persian for “brocade”), paithani (whose pattern is identical on both sides) and mushroo (satin weave). All three techniques came to Hyderabad in the 17th century, thanks to the Persian artisans who worked in the court of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. Later, the nizams patronized textile weavers, but with the decline of the dynasty’s fortunes, these fabrics all but disappeared.

“Andhra Pradesh has a very rich textile heritage,” Bose says as she potters around her cluttered store, counting bolts of cloth and hand-painted kalamkari cotton, another local specialty. “I’m just trying to keep it alive.”

So are Hyderabadi fashion designers like Anand Kabra, who fuses traditional weaves and embellishments into his collections. I discover his work at the spare Elahe boutique in Banjara Hills, where a youngish clientele confidently mixes and matches Indian skirts and halter-necked tops. Down the road, in the glitzy Mangatrai pearl showroom, dowagers clad in crisp saris pick through pearls the size of giant peas.

Done with window-shopping, I retreat to the Park hotel’s Aish restaurant, where chef Mandaar Sukhtankar serves delicious Hyderabadi food in a fine-dining environment. I sit down with a group of locals to gorge on aromatic biryanis, flavorful haleems (a rich stew of ground meat, wheat, lentils, and spices), moist tandoori kebabs, and curried vegetables. At the end of the meal, someone hands me a betel-nut digestif called paan. I pop it into my mouth, and its sweet juices spurt out—one of life’s small pleasures in a city that knows how to savor them.

The Details: Hyderabad

Getting There

Silk Air (silkair.com) flies daily from Singapore to Hyderabad’s Rajiv Gandhi International Airport; from Bangkok, Thai Airways (thaiair.com) operates four flights a week. The city is also well connected to Delhi, a two-hour flight away, and other major cities in India.

When to go

Situated 520 meters above sea level on the Deccan Plateau, Hyderabad has a relatively pleasant climate for a major Indian city. The weather is generally at its best from mid-November to March, when skies are typically clear and temperatures remain below 30ºC.

Where to stay

- Park Hyderabad 22 Raj Bahwan Rd., Somajiguda; 91-40/ 2345-6789; theparkhotels.com; doubles from US$369

- Taj Falaknuma Palace Engine Bowli; 91-40/ 2438-8888; tajhotels .com; doubles from US$765

Where to eat

- Fusion 9 A stylish multi-cuisine restaurant in Banjara Hills. 6-3-249/A, 1st Ave., Rd. No 1; 91-40/6557-7722.

- Paradise Restaurant Paradise Circle, M.G. Rd., Secunderbad; 91-40/2784-3115. Aish 22 Raj Bahwan Rd., Somajiguda; 91-40/2345-6789.

What to See

- Chowmahalla Palace Khilwat, 20-4-236, Motigalli; 91-40/2452-2032; chowmahalla.com.

- Golcanda Fort

Originally appeared in the April/May 2011 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“The Treasures of Hyderabad”)