Above: Tables set for dinner under a mahua tree at Bandhavgarh National Park’s Mahua Kothi, one of four luxury lodges run by Taj Safaris.

The national parks of Madhya Pradesh are home to nearly a quarter of India’s remaining tigers, as well as a host of other exotic creatures. And while the big cats are increasingly elusive these days, comfort is guaranteed at a quartet of luxury safari lodges

By Jason Overdorf

Photographs By Christopher Wise

Skidding his JEEP to a stop in the jungles of Bandhavgarh National Park, Kartikeya Singh Chauhan craned his neck to examine the rutted forest track. “See there,” he said, pointing to impressions in the feather-soft sand. “Fresh pugmarks.” A tiger was close.

“Pichey! Pichey!” our minder from the state forest department shouted. “Back up! Back up!”

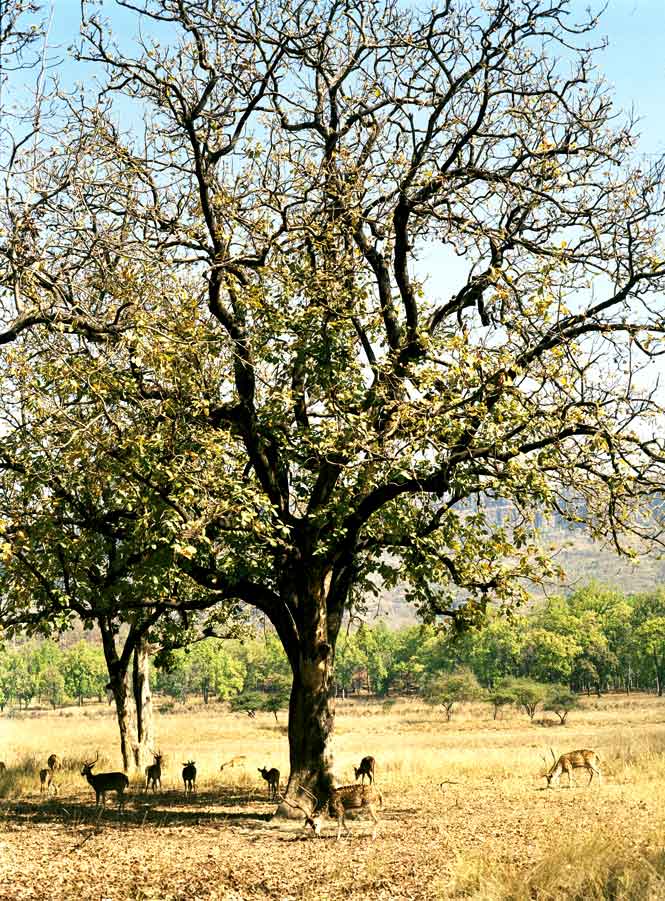

Chauhan slammed the jeep into reverse and raced up a gravel incline, then stopped and motioned for silence. We cocked our heads to listen. A moment later came the short, chirping warning call of a spotted deer. The barks grew louder as we roared forward again, and then, rounding a bend, we found ouselves face-to-face with the big stag that was sounding the alarm. “They’re here,” Chauhan announced. “It’s the cubs.”

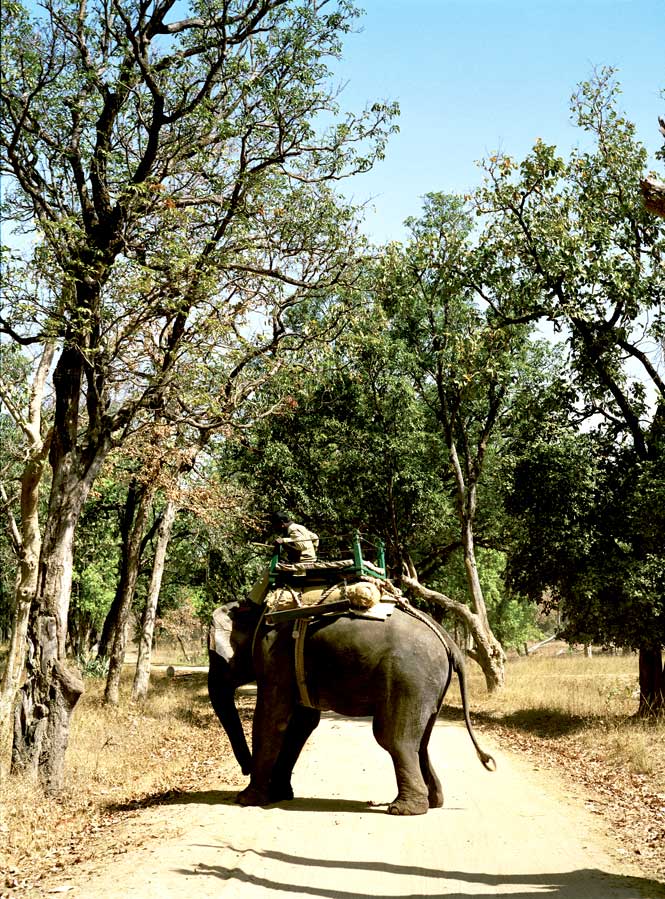

About 18 months earlier, one of Bandhavgarh’s tigresses had given birth. Today, the two adolescents were learning to hunt, sending the deer and other game crashing through the brush to escape. Chauhan sped down the track after the noise until a forest guard pushing a bicycle motioned us from the road. “You just missed them,” he said. “They crossed the path, and they’re over there.” He pointed toward a dry slope forested with broad-leafed teak and sal trees.

Suddenly, a herd of spotted deer bounded across a clearing. “Here he comes,” Chauhan said.

“He’s chasing them.” Then a wild boar dashed through the gap in the trees. Close on its heels loped a graceful young tiger. In an instant, it was gone. I hadn’t snapped a photo. I hadn’t even blinked. “Wow!” I said.

Not terribly articulate, I know. But I was stunned. This was my fourth trip to India’s jungles to look for tigers, but on the first three I hadn’t so much as heard an alarm call. I’d pretty much resigned myself to the idea that India’s remaining great cats would be wiped out before I had a chance to see one in the wild.

Everybody knows that the tiger is endangered. But recently the situation has been revealed to be worse than we thought. For its latest tiger census, India abandoned its old method, which extrapolated numbers from counting tiger tracks, and adopted a complex system that uses satellite remote sensing and camera trapping, among other techniques. The results were startling: instead of the 3,600 tigers estimated to be living in India’s forests in 2002, the more sophisticated census indicates that there are only about 1,400. In other words, either two-thirds of India’s tigers were killed over the past six years, or they had never existed anywhere but on paper.

Home to six tiger reserves and the setting for Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh could be the front line in the battle to save the big cat. With tigers, leopards, and wild buffalo —three out of India’s “Big Five”— and forests that teem with sloth bears, monkeys, deer, antelope, jackals, and wolves, the state has enormous tourism potential. But due to poor management it has never become a safari destination on the order of South Africa or Kenya, and there are signs that the situation is about to get worse. A highway alongside one of its best tiger reserves is to be widened as part of a government expressway project, while at another reserve, police and forest department officials are refusing to work together, instead blaming each other for the deaths of at least a dozen tigers since November 2008. Worst of all, by embarking on a much-criticized plan to import tigers from other reserves, the forest department tacitly admitted recently that it had allowed poachers to wipe out all the tigers of Panna National Park.

My guide, Chauhan, was hip-deep in the controversy. A quiet, diminutive man with a Rajput’s handlebar mustache, he is the head naturalist at the three-year-old Mahua Kothi, one of four luxury lodges opened in Madhya Pradesh by Taj Safaris, a joint venture between India’s Taj Hotels Resorts and Palaces and Johannesburg-based &Beyond (formerly CC Africa). A former wildlife researcher who studied the Asiatic lion, Chauhan is helping to push forest officials to adopt new management philosophies and to raise the standard of service provided by park staff. So far, however, Indian wildlife activists remain skeptical about how multimillion-dollar resorts will affect the country’s tiger reserves. “Tiger tourism in particular is all about making money,” Belinda Wright, who heads the Wildlife Protection Society of India, had told me in Delhi before I left on my trip. “Even though there are groups that are talking about better practices and things, we haven’t really seen them in action.”

That was what I had come to the jungle to do.

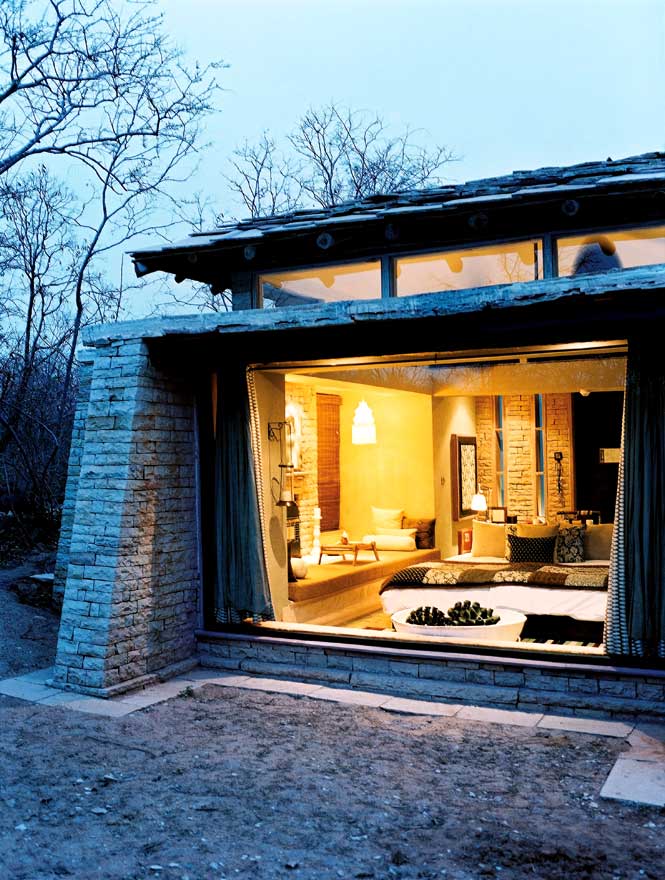

The night before, photographer Christopher Wise and I had bumped and rattled our way to Mahua Kothi in pitch darkness after a typically Indian day of airport delays and rough roads. As it turned out, our hosts were ready for us. Neel Gogate (the lodge’s general manager), Mahendra (our butler), and the rest of the hospitality crew were waiting with ice-cold towels and glasses of lemonade; Mahendra had already drawn baths in our rooms, sprinkling the water with flower petals and lighting enough candles for a saint’s shrine; and the chef had whipped up a classic thali—the degustation menu of delicacies that lies at the heart of any gourmet Indian kitchen. Gogate cut straight to the chase. “Would you like to have a bath first, or would you prefer a drink?” he asked.

Dinner was stupendous. Chef Siddarth Sarmah has wisely eschewed an à la carte menu, instead creating his own selection each evening so that he can introduce guests to more varied fare than the chicken curry, dal fry, aloo gobi, and palak paneer that otherwise becomes the staple diet of unenlightened foreign visitors. Along with some succulent mutton curry, we were treated to an elegantly prepared ragout of karela (a delicious, knobby bitter gourd that is almost impossible to find on restaurant menus), a dish of spiced and sautéed pumpkin that I still lie awake thinking about from time to time, and a subtle pulao made with fragrant rice and the buttery flower of the mahua tree, from which the lodge derives its name. I’d learn about Mahua Kothi’s conservation plans later. But for now, it was clear that these guys had the luxury thing down pat.

That was the first goal of Taj Safaris, a venture that was essentially knocked into place over cocktails by three high-powered pals from the hospitality trade: Steve Fitzgerald, Beyond’s chief executive; Rajiv Gujaral, the Taj group’s chief operating officer; and entrepreneur Binod Chaudhary, president of Nepal’s largest conglomerate. “The idea was to harness the combined experience of Taj and &Beyond to create a world-class luxury Indian safari experience,” Beyond’s commercial director, Gary Lotter, told me. To that end, the partners spent five years identifying properties, designing and building their resorts, hiring and training staff, and developing their relationship with the Madhya Pradesh forest department.

At Mahua Kothi, the first of the four lodges to open, Goan architect Dean D’Cruz designed 12 Ralph Lauren–rustic cottages based on the traditional Madhya Pradesh kutiya, a rough-hewn hut with walls made of mud and cow dung and topped by a thatched roof. A beautiful khaki color with a fine matte texture, the thick walls are impervious to the late season’s 35°C heat. Better still, by using indigenous materials, the lodge has not only reduced its carbon footprint but also provided ongoing employment for the local village women, whose job it is to apply a fresh coat of mud and dung after the monsoon each year, as they do for their own homes. My cottage had its own little courtyard with a rope charpoi for lounging. And even though the buildings are clustered close together to make the most of the property’s small hectarage, D’Cruz had managed to orient each of them toward the jungle, giving guests the illusion of being alone in the forest.

Taj and &Beyond are not the first to bring luxury to India’s wilds. Both the Oberoi group and Amanresorts have been operating luxurious tented camps near the Ranthambore tiger reserve in Rajasthan for six years or more. Similarly, though Mahua Kothi runs conservation-awareness programs for local schoolchildren and provides school supplies for them with guest donations, its ad hoc endeavors struck me as neither better nor larger in scale than comparable efforts by other Indian lodges I’ve visited.