Above: Overlooking the rooftops of Kathmandu’s Khusibun neighborhood.

Nepal’s capital may not be the city of innocence it was 20 years ago when he wrote Shopping for Buddhas, but for author Jeff Greenwald, Kathmandu continues to captivate

Photographs By Martin Westlake

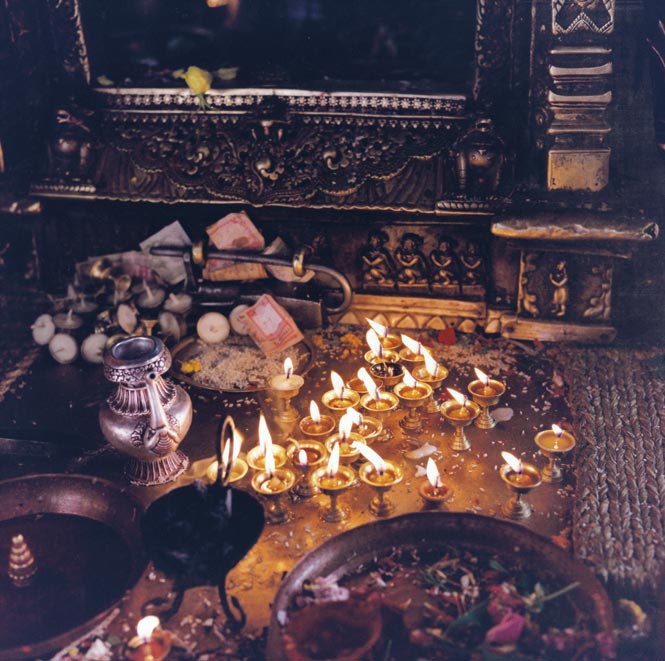

The festival of Indra Jatra,

Which falls during September’s waxing moon, is one of the Kathmandu Valley’s most beloved holidays. As with all Nepali celebrations, its origin is maddeningly complex. Put briefly, it commemorates the capture of the rowdy god Indra, who was caught stealing a bouquet of the valley’s famous jasmine. In return for his freedom, the trussed-up deity agreed to provide the morning mists of autumn, essential to the cultivation of winter wheat.

Last year, as always, thousands of Nepalis gathered for the culmination of the festival. After parking my rented motorcycle near a vegetable market, I followed the celebrants flowing into Kathmandu’s broad Basantapur Square. The ancient palace plaza quickly filled with families arriving for the evening’s colorful dances and rituals.

At the climax of Indra Jatra, water buffalo are sacrificed to honor Kumari, the Living Goddess: a real-life, prepubescent girl who serves as the valley’s protector. This time, however, there was a delay—then the unthinkable occurred. Nepal’s newly elected Maoist leadership declared, at the height of the ceremony, that government funds would no longer be used to supply sacrificial animals.

The reaction morphed instantly from disbelief to violence. Riots broke out, and the usually jubilant festival turned into a melee. I grabbed my daypack and fled the square, amazed at how profoundly the country had changed since I first fell in love with it three decades ago.

It was July of 1979. The brief entry in my journal from my first day in Nepal reads, “Welcome home.” I stayed five months before tearing myself away, returning in 1983 on a yearlong journalism fellowship. I’ve come back to Kathmandu nearly every year since. My best-known book, Shopping for Buddhas, was written here in 1988, a time of crisis for Nepal. The brief volume focused on my search for the “perfect” Buddha statue, a theme that served as a foil for exploring the city and observing Nepal’s halting steps toward democracy.

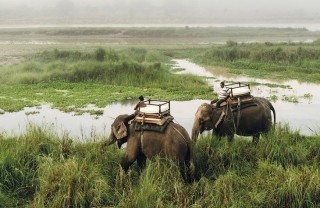

The changes I’ve seen since then have touched every facet of life in the country: from the tragic civil war to the royal massacre in 2001; from the runaway development of the Kathmandu Valley to the emergence of China as an eager and bossy ally. Kathmandu is no longer the place of innocence it seemed in the 1980s, when I shopped for Buddha statues in uncrowded bazaars or strolled down narrow lanes past the wary gaze of sacred cows. In May 2008, when the centuries-old monarchy was abolished and a Maoist government took over, even the country’s exotic tagline—“the World’s Only Hindu Kingdom”—became obsolete.

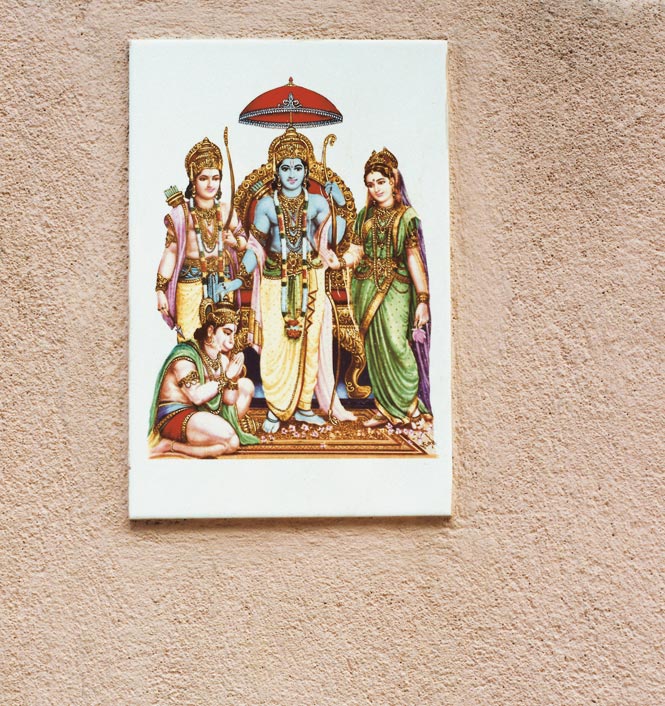

And yet despite the chaos and pollution, I find Kathmandu today as beguiling as ever. An hour before sunset, when the mugginess of the late monsoon begins to subside, paper kites fill the air, fragile squares jumping in the breeze. In a labyrinthine alley near the busy market of Indra Chowk, necklace-weavers await customers amid curtains of shimmering glass beads. And along Thamel’s funked-out streets or across the valley in Patan (Kathmandu’s sister city and center of the bronze-casting trade), rustic storefronts still display a pantheon of fabulous deities, masterworks in copper, brass, and silver.

Twenty years ago, researching Shopping for Buddhas among the curio shops of Kathmandu and Patan, I knew exactly what I was looking for: a seated Buddha in “Touching the Earth” pose. The image would serve as a point of concentration, a hedge against the demons of distraction. Now, I’m not at all sure what I’m shopping for. It will have to be something reflective not only of me, but of my relationship with Nepal itself—a talisman to help me face the changes, to help me focus on the magic that remains.

In 1968, American ecologist Garrett Hardin wrote an essay called The Tragedy of the Commons, describing an all-too-familiar social dilemma in which individuals, behaving out of self-interest, destroy a shared resource.

Much as I love Kathmandu, it’s hard to visit the once charming, bicycle-filled valley without thinking about Hardin. Modern Kathmandu appears to be the product of 50 years of bad choices, one right after another. But while the march of billboards, urban congestion, and maddening traffic are collective ills, it takes a personal trauma to really bring the point home.

For my latest visit, I’ve arranged to sublet an apartment from friends. It’s on the upper floor of a handsome brick house in the Ghairidhara area, with prayer flags strung across the roof. My friends, who have been out of town since early summer, told me all about the place: how they practiced yoga on the peaceful veranda, and watched sunsets from the roof. Their windows, they said, overlooked fields planted with corn, rice, and flowers.

These days, however, real estate in Kathmandu is at such a premium that open space is seen as a waste, and zoning regulations are nearly nonexistent. One month before my arrival, the fields adjoining the apartment were rented out—to a salvage yard. From dawn to dark, at least 30 day laborers smash bottles into pieces and hammer apart old metal gates. It’s like living next to a found-art drumming troupe that specializes in abstract compositions played on bent bicycle rims, oil cans, and Carlsberg bottles.

I pack up my laptop and escape to one of the city’s few bona fide oases, the Garden of Dreams. Once the private estate of Field Marshal Keshar Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana, the property fell into neglect during the 1960s. After years of restoration by expert landscapers and architects, the walled compound was opened to the public in October 2006. With its fountains, koi ponds, neoclassical pavilions, and shade trees, the garden has become a refuge for creatures of every stripe—from songbirds and squirrels to love-struck couples and agitated journalists.

In a city as manic and congested as Kathmandu, the key to enjoyment is finding hidden treasures. The Garden of Dreams is a worthy addition to the list. Here, I’m able to indulge a favorite Kathmandu pastime: closing my eyes, and just listening. The variety of sounds is amazing: a toy whistle, the rumble of a jet, barking dogs, an occasional firecracker, shouting voices, taxi horns, crows, bicycle bells, hammering on metal, children singing.

That aural tapestry is one of the things I love most about Nepal. Maybe, then, I ought to get myself a statue of Milarepa, the 12th-century Tibetan poet/saint who is portrayed with his right palm cupped to his ear, listening to the music of the spheres.

Though Nepal has entered the Information Age, an obscure law of physics seems to forbid anything happening efficiently. Everything takes far longer than one might expect, given the outward appearance of progress.

Twenty years ago, for instance, phoning overseas from Kathmandu was an adventure. I had to figure out the time difference, then ride my bike to the Telecommunications Bureau (often in the wee hours) to place a trunk call. I’d fill out a form, take a seat, and wait two hours to learn that my mother’s line was “engaged.” If my call actually did go through, it sounded like I was talking to an astronaut marooned on Mars.

These days, making a call from here to anywhere—within Nepal or across the planet—is a cinch. One simply buys a SIM card and dials away.