Above: Monks on Sisowath Quay, the city’s popular riverfront promenade.

Putting the turbulence and tragedy of the last quarter of the 20th century behind it, the Cambodian capital is looking to an earlier era for inspiration as it reemerges as a city of arts and culture

By Dustin Roasa

Photographs by Martin Westlake

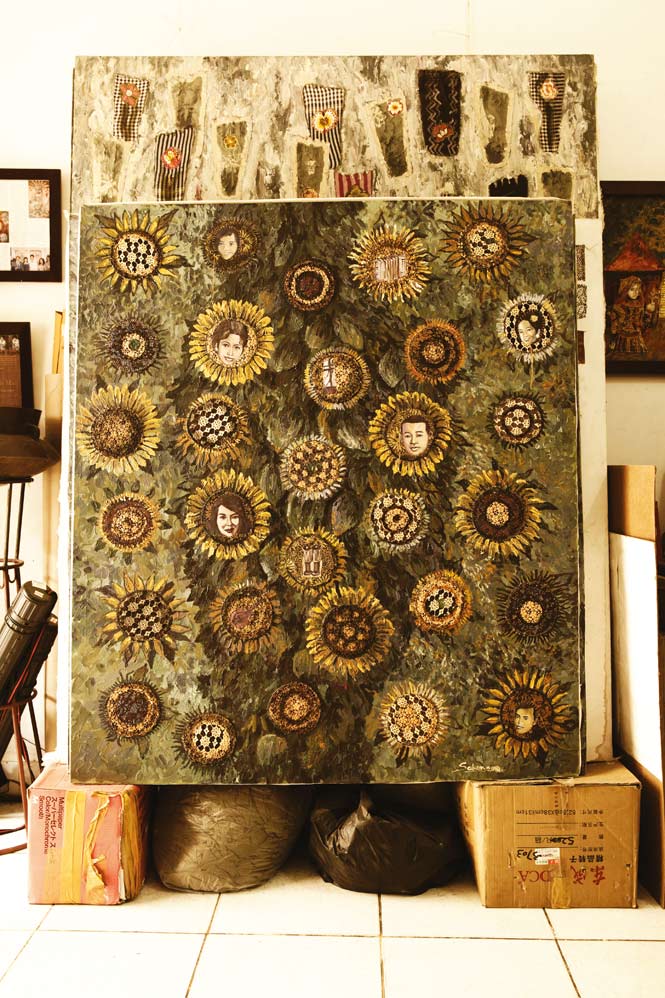

Down a side street near the Art Deco arches and mustard-yellow dome of the Central Market, Phnom Penh’s budding creative class gathered in February to celebrate the homecoming of one of its own. Cambodian artist Leang Seckon, back from a successful show at the Rossi & Rossi gallery in London and the subject of a recent glowing profile in the New York Times, glided around the white interior of the French Cultural Center, which was hung with his latest show, “Shadow of the Heavy Skirt.”

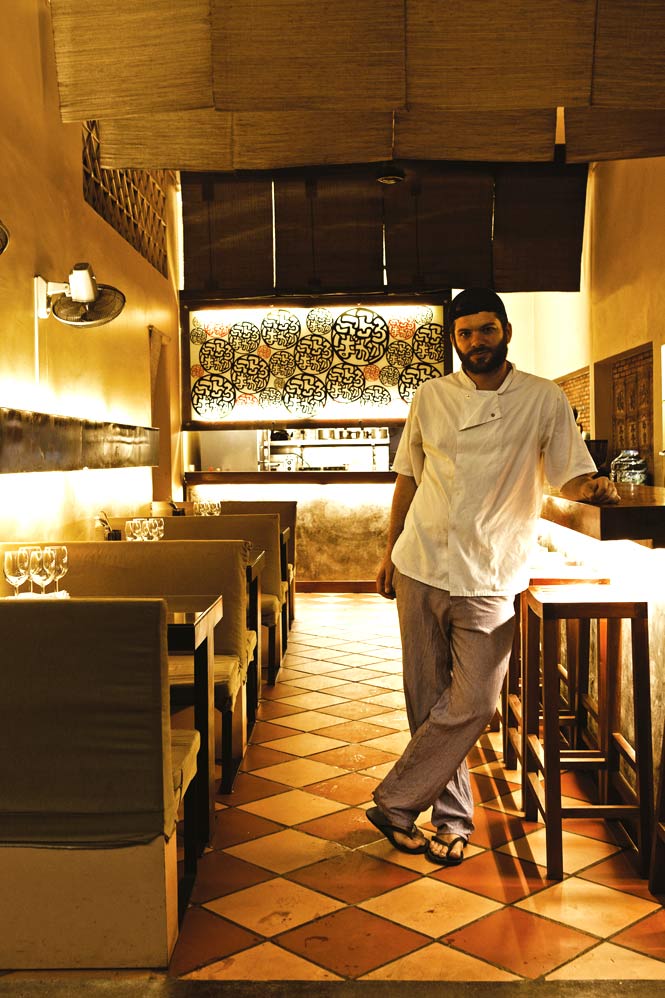

As he greeted friends and admirers with his trademark soft-spoken warmth, several hundred people—diplomats in gray linen suits, art students in drainpipe jeans, expat scenesters in thick-framed glasses—lingered in front of the artist’s canvases. With their reverential depictions of 1960s Cambodian rock-and-roll icons like Pan Ron, their freighted references to Khmer Rouge relics like the Mao cap, and their whimsical renderings of contemporary objects like mobile phones and KFC outlets, the collage-like oil paintings captured the mood of a city in transition, but one that is rediscovering its vitality and confidence after years of conflict and stasis.

“The entire city is developing before us. Roads are being paved and skyscrapers are being built,” Seckon told me several days later in his spartan storefront gallery near the Royal Palace. “People are excited about all of these changes. But they are also overwhelmed with modern life, so they are looking to the past and reconnecting with their roots.”

It is conventional wisdom to say that Cambodia is captive to its past. What this usually refers to is the Khmer Rouge, the communist regime that ruled the country from 1975 to 1979. During those terrible years, an estimated 1.7 million people—more than 20 percent of the population—were killed, many of them city dwellers who were marched off to work camps from which they would never return.

The reign of the Khmer Rouge and the occupation by Vietnam that followed left a catastrophic imprint on Cambodian society that is impossible to understate. But in recent years, as distance has dulled the pain of those traumas, Phnom Penh’s residents have begun to look to the years that predate the country’s turmoil, finding inspiration in the elegance of the French-colonial era or the golden years of the 1960s, when the city was a center of architecture, art, and filmmaking.

Galvanized by this, Cambodian and foreign entrepreneurs are helping to remake Phnom Penh into one of Asia’s most underrated and dynamic—but still easygoing—capitals. Stylish boutique hotels and shops are popping up in once dilapidated colonial and Modernist buildings, and pockets of art and culture are taking hold in neighborhoods that previously offered little of either. Dozens of restaurants and bars open every month, creating a nightlife scene that is startlingly cosmopolitan and fast-changing for a city with an official population of two million. Not bad, then, for a place that a decade ago was desperately short of electricity and paved roads.

But for all this modernization, Phnom Penh, my home for the last three years, manages to retain an essentially Cambodian—which is to say, rural—character. Unlike densely urban Bangkok or Ho Chi Minh City, Phnom Penh feels like an extension of the Cambodian countryside. This is partly because it is small—you can travel almost anywhere in 10 minutes—but it is also a matter of demographics. Most of the city’s pre–Khmer Rouge residents died or fled the country; today, the city is populated largely by migrants from the countryside.

Days in Phnom Penh ebb and flow to the cadence of rural life. The city is in full swing by sunrise, the traditional start to the morning for farmers, when it’s possible to hear roosters crowing in the central districts. In the narrow alleys and lanes hidden from view behind concrete shophouses, workers and moto-taxi drivers tuck into bowls of kuey tiew—rice vermicelli with thinly sliced beef served in sweet broth—while middle-aged women pound out curry paste with wooden mortars and pestles, creating a symphony of rhythmic plonking. Buddhist Monks dressed in bright orange robes visit the city’s shops and businesses, offering blessings in exchange for alms or a bite to eat. Families and neighbors chitchat on raised wooden platforms, perpetuating a ritual that has been playing out in the countryside for generations.

As Yam Sokly, an architect and local historian, put it to me, “Phnom Penh has the feel of a small town, even though it is becoming a big city. I think it surprises visitors, because it still has this sense of community.” Sokly was born to a family of migrants from the provinces and grew up in the Phnom Penh of the 1980s, when cows and pigs wandered the streets and giant banana and coconut trees formed the closest thing the city had to a skyline. The neighborhood around the Olympic Market in the southwest part of the city, where he grew up and still lives, is as tight-knit as it was when he was a boy. “At five o’clock, all of the old people come out of their houses to share food and gossip. They have their own parliamentary meet-ings out there on the sidewalks,” he said.

But as Sokly and his generation—those under 30, who make up 75 percent of Cambodia’s population—have grown up, they’ve come to see Phnom Penh as much more than a place for fostering traditional bonds. “You can feel the vibrancy of the city now. My favorite thing to do on the weekends is to wander the streets and look at the diversity of the architecture, the new and the old, and to explore hidden areas that I didn’t know existed,” he said. “But we’re finding that progress is not always good. I worry sometimes that the city will soon become like Ho Chi Minh City, where all of the old buildings have been knocked down and replaced by high-rises.” Such change has hit Phnom Penh’s poor particularly hard, with the country’s newspapers carrying headlines nearly every day about large-scale evictions leaving farmers and laborers homeless and landless, often overnight.