Sokly is not alone in his concerns about indiscriminant development. But the overriding consensus among residents is that Phnom Penh is growing into itself and finally fulfilling some of the promise that was so cruelly snatched away by three decades of violence and turmoil. To understand what that means, one must look back to a more optimistic era.

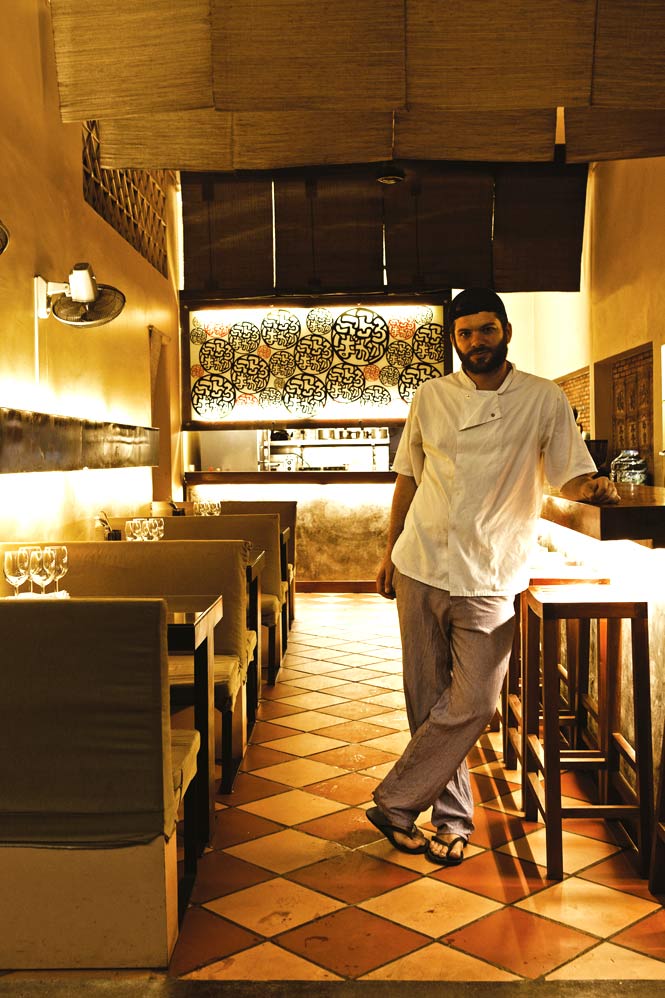

Above, from left: The Chinese House’s Tepui restaurant; the upstairs dining room at Tepui; the dome of Phnom Penh’s Central Market; a 19th-century depiction of Wat Phnom, the city’s namesake.

On a Saturday night about a year and a half ago, in a desolate riverfront neighborhood near the container port on the Tonle Sap River, a renovated trader’s mansion called the Chinese House hosted a party that captured an undercurrent in the city that has since bloomed into a full-fledged cultural moment. The evening was a celebration of Cambodia’s vibrant film industry in the 1960s—Phnom Penh then was home to dozens of cinemas and prolific filmmakers, including Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who made over 30 movies —and the artistic and political atmosphere that nurtured it.

That night, Cambodians in their twenties, many of them university students, arrived on motorbikes dressed in the clothing of another generation. The boys wore white tuxedos, black bow ties, and pomade-sculpted side parts, channeling legendary rock crooner Sinn Sisamouth, the Cambodian Elvis. The girls, meanwhile, wore colorful miniskirts and elaborately constructed beehives, much like the actresses depicted on the vintage movie posters adorning the walls of the ground-floor gallery and performance space. Mixed in with this young crowd were actors, directors, and producers who had survived the Khmer Rouge’s killing fields.

Soon, a French DJ with angular Nico bangs began spinning LPs by artists such as Ros Serey-sothea, whose Khmer-language, Janis Joplin–like howls sounded otherworldly through the thick static of the old vinyl. Giddy students flooded the floor and danced for hours to this music, which Cambodian artists had created after hearing American rock played on armed forces radio during the Vietnam War. Here were Cambodians experiencing the past with joy—not sadness—in an evening that captured their collective longing for a time when Phnom Penh was ascendant and the envy of much of Southeast Asia (while touring Phnom Penh in 1967, Lee Kuan Yew, prime minister of the then-fledgling Republic of Singapore, reportedly remarked: “I hope, one day, my city will look like this”).

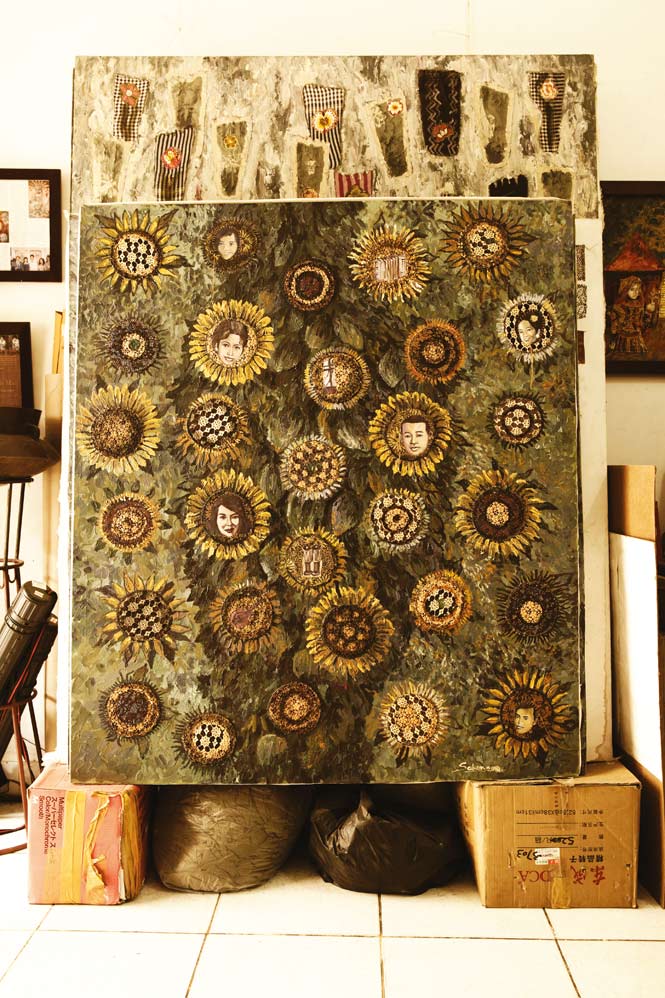

Actress Dy Saveth, who starred in more than 100 films during the 1960s and early ’70s, remembers a Phnom Penh of imaginative architecture, lavish parties, and a thriving creative community. “We would meet every day to talk about our work and to laugh and joke. We felt that anything was possible then, because the country was stable and we trusted the government,” she told me. Saveth, a striking woman with palm-sugar-colored skin and bewitching black eyes, fled Cambodia in 1975, catching a helicopter flight out of Phnom Penh as mortar shells exploded around her. Nearly 40 years later, sitting in her modest, middle-class apartment decorated with stills from her many films, she said how pleased—and surprised—she is that people are rediscovering the city’s golden age.

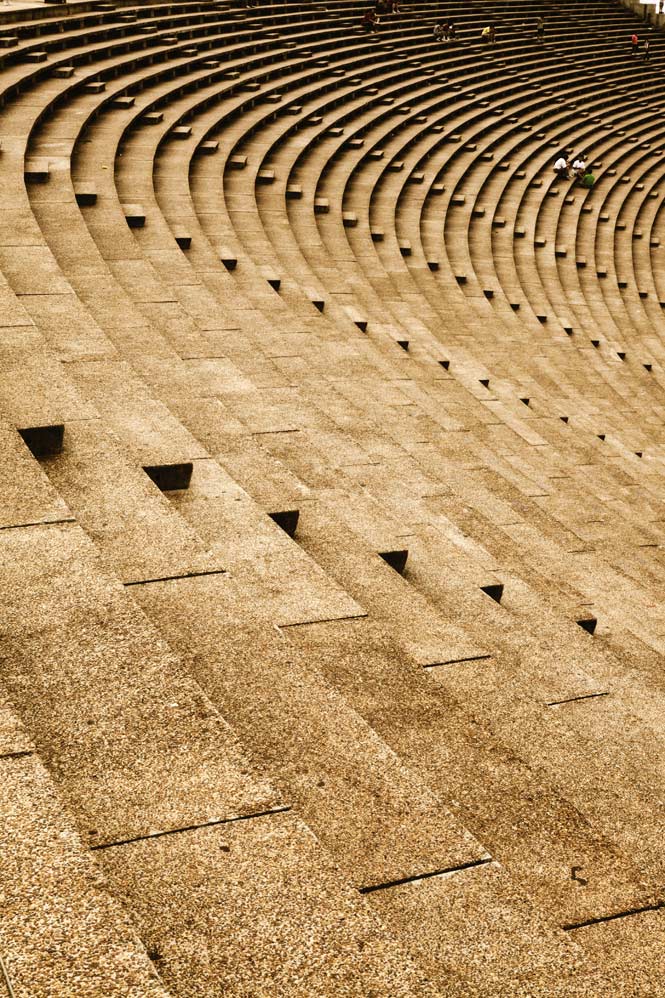

In the weeks and months following that party at the Chinese House, there were similar events throughout the city, each celebrating a different aspect of 1960s Phnom Penh that had nearly disappeared from collective memory. One was a retrospective of Vann Molyvann, Cambodia’s most gifted architect, whose daring, Le Corbusier–inspired buildings reference Cambodian and Buddhist symbols. Although some of his structures have been torn down to make way for new malls and office complexes, many of his masterpieces, including the National Sports Complex, stand as reminders of the decade’s go-getting ethos. Khmer Architecture Tours, which offers guided tours of these structures led by Cambodian students, is a must-do for visitors hoping to learn more about this legacy.

Meanwhile, Dengue Fever, a Los Angeles–based band heavily in-spired by Cambodia’s 1960s rock scene, has visited Phnom Penh twice in recent years and has almost single-handedly revived interest in this near-forgotten music, in the process putting Phnom Penh on the map for hipsters from New York to Berlin. A local promoter sought to capitalize on this buzz by bringing in counterculture icon Leonard Cohen for a performance last year. Although the concert was canceled due to logistical reasons, the fact that it was Cohen’s only scheduled Southeast Asian date—and was expected to attract attendees from as far as South Korea and Singapore—perhaps says something about Phnom Penh’s ambitions to once again be a cultural touchstone.

Helping to drive this resurgence is a small group of Westerners who covet the openness of the city—and the invitation it offers to try things they never could in their home countries. “Cambodia is a new nation, so there’s lots of space for creativity. It’s a paradise for entrepreneurship,” said Alexis de Suremain, who owns or co-owns some of the city’s most innovative properties, including the Chinese House. De Suremain’s hotels, bars, and restaurants have widely varying identities that cater to seekers of an imagined—or, in some cases, real—Cambodia.

If you want the romance of the French colonial era, there’s his Pavilion Hotel, which inhabits a restored 1924 villa built for the mother of former king Norodom Sihanouk.

If it’s modernism you seek, there’s the Blue Lime, whose concrete minimalism evokes Vann Molyvann. Then there’s perhaps de Suremain’s most ambitious project, a 1940s mansion in the heart of the city that will open as a hotel in November called The Plantation.

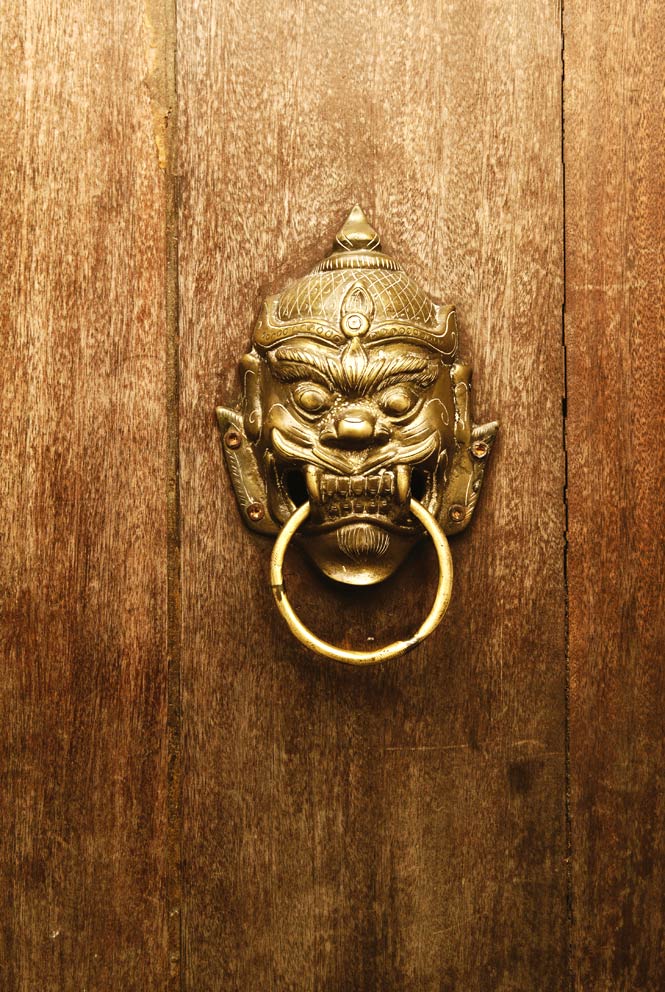

Above, from left: a waitress at Naturae, a vegetarian restaurant near the Royal Palace; a door knocker at The Pavilion; a bedroom at The Pavilion; poolside at The Pavilion.