Across Taiwan’s capital, restoration projects and a democratic approach to urban planning are transforming the city from the ground up. Here’s a fresh look at one of the most livable places in Asia.

Photographs by Christopher Wise

A DJ at the opening of an exhibition by Spanish cartoonist Joan Cornellà at Huashan 1914 Creative Park.

Technically, it was well into autumn but the heat was still intense enough to force me to pause halfway through a long afternoon exploring Huashan 1914 Creative Park, a sprawling nature-slash-cultural complex smack in the middle of Taipei. I made my way to what look liked an open field populated by picnicking families and a few canoodling couples. A wide-open, hilly stretch of grass extended all the way to an elevated expressway in the distance, empty save for a few stately trees and toddler-filled sand pits.

As I flopped onto an inviting bench in the shade, I tried to figure out why things didn’t feel quite right. Then it hit me—it was the field itself. In the typical Asian metropolis, a prime swath of land like this would be in the throes of commercial or residential construction; perhaps home to a monument of some sort or at the very least fenced off and landscaped. But the more I learned about Taiwan’s capital, the more I came to see this untouched patch of greenery (a former railway yard, I later discovered) as emblematic of its rather different approach to planning and development—an approach that has produced much to delight residents and visitors alike.

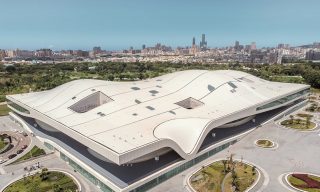

There are many ways to evaluate a city, and by a lot of them Taipei is a fair to middling performer. Much of its architecture is drab and utilitarian, the inheritance of decades of rapid industrialization. Beyond the (excellent, it must be emphasized) National Palace Museum, there are no big-ticket attractions. The city’s most iconic landmark—the Taipei 101 tower, completed in 2004—enjoyed only a brief stint as the world’s tallest building before it was eclipsed by the gargantuan Burj Khalifa in Dubai, and now barely scrapes into the global top 10. Hong Kong and Singapore are by most accounts better places to shop.

But when it comes to making the most of what it does have, Taipei excels, as witnessed by an impressive run of restoration and beautification initiatives. Huashan 1914 opened in 2005 on the site of a long-defunct rice wine factory. The former squatter settlement of Treasure Hill made its debut as a revamped “artist village” in 2010, followed the next year by the completion of a 111-kilometer network of riverside bike paths. And in 2015, eastern Taipei’s notorious Neihu landfill (not-so-affectionately dubbed Trash Mountain by locals) was converted into a 16-hectare ecological park.

And the rest of the world appears to be taking notice. Taipei is now one of the highest-ranked cities in Asia on global livability and sustainability indexes, and was named 2016’s World Design Capital by the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design for its efforts to “reinvigorate” the urban landscape. This is clearly good news for mayor Ko Wen-je, who recently brushed off criticisms that the administration’s vision for the capital was not “flashy” or “grand” enough by stating its top priority was “building a city where people can live their life happily.”

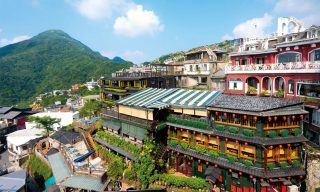

Aside from headline-grabbing projects like Huashan 1914, this means that a lot of the interesting transformations are happening at the neighborhood level. To understand them, one should start where Taipei essentially began: the western district of Dadaocheng bordering the Tamsui River, which in the mid-19th century emerged as a key port for the burgeoning tea export trade. Populated by foreigners and merchants, it flourished in the early stages of Japan’s 1895–1945 occupation of Taiwan, boasting landmarks such as Taipei’s first rail station and modern movie theater. The fortunes of many of the families that dominate Taiwanese business to this day were based in the shops and godowns that crowded Dadaocheng’s Dihua Street.

Nonetheless, the city’s center of gravity soon shifted decisively eastward as its Japanese administrators erected the trappings of power in the more spacious Zhongzheng district, which is still home to most government offices and a fine legacy of baroque and neoclassical buildings like the stately Presidential Office (originally the base of the Japanese governor-general). More recently, as a new central business district mushroomed in Xinyi, even farther from the city’s old port, Dadaocheng was left to quietly go to seed.

Until, that is, it served as the basis for an experiment. For much of its history, Taipei had adopted the same blunt method of urban improvement as other Asian cities, essentially tearing down old neighborhoods and building new ones. But in a nascent democracy this often gave rise to dislocation and protest. “In the past we tended to focus on the ‘hard’ infrastructure, but we realized we were neglecting the ‘soft’ part of the urban fabric—the communities,” says Hu Ju-chun, an official at the city government’s Urban Regeneration Office.

The URO sums up its new strategy as “urban acupuncture”—that is, small, selective changes that attract the flow of visitors and commerce (i.e. “energy”) to neglected areas, and reclaim abandoned spaces through which energy is “lost” and that therefore have a negative impact on their surroundings. The “needles” in this model are known as Urban Renewal Stations (URS), typically old or underutilized buildings that are repurposed based on the suggestions of residents, students, artist groups—basically whoever wants to speak up.

The URO provides an online platform to collect and discuss these ideas. It may help a group negotiate with a building owner or provide some token funding to get an activity started, but the agency is basically hands-off, taking the view these stations should evolve (or fail) organically. The result is a somewhat bewildering—but promising—assortment of venues, from outdoor music platforms to design workshops, popping up in previously blighted places.

To see how this urban acupuncture works in practice, I head to Dadaocheng’s Dihua Street. The first thing I notice is the area’s energy. Scooters piled high with boxes duck and weave through its narrow lanes, so different to the broad boulevards of modern Taipei; jumbo cans of cooking oil and barrels of pungent medicinal herbs spill onto the sidewalk; and crowds mill respectfully around the incensed-wreathed Xiahai City God Temple. The second thing that strikes me is the buildings, a lovely hybrid of Chinese shophouse and prim, Victorian-style red brick, some with elaborately carved facades and many slightly worse for wear.

Having made a beeline for URS 127 Art Factory (the stations are named for their street number and theme), I quickly discover these old structures are even more impressive on the inside. Lofty ceilings and long, narrow rooms extend back for what seems like miles before opening onto intimate walled courtyards, which in turn give way to yet more rooms, like a house of mirrors. In the Art Factory’s case, these spaces are given over to a shop selling curios from local design houses like Uncle and Sister, a maker of stationery emblazoned with kaleidoscopic cartoons (often of Dadaocheng street scenes), as well as a top-floor studio and exhibition hall and (in the aforementioned courtyard) a pop-up alfresco café.

Just up the street, URS 155 Cooking Together inhabits similar historic digs but is a very different beast. At street level it’s a boutique highlighting specialist local provisions such as dried fruit and spice mixes from venerable, family-run Tuan Yuan. However, a whirlwind tour led by a gregarious clerk who calls herself Jamie soon reveals there’s also room for a large communal kitchen where people can gather to try out recipes, and residencies for local artists in need of a place to work. “But the food is the main thing,” Jamie confides. “We’re working to promote Taiwanese products that have been around for generations to a whole new group of consumers.”

Food is also a focus at URS 329 Rice and Shine, a cavernous old building on Dadaocheng’s northern fringes that once housed a rice wholesaler. Vacuum-packed bags of jet black and pearly white rice from organic farms nationwide are displayed invitingly on the shelves, alongside other agricultural treasures like plum juice, kitchen implements, and culinary-themed handicrafts. As at other URS properties, areas have been set aside for exhibitions; on my visit, a series of images taken by Taiwanese photographers of daily life in Vietnam took center stage.

While it might be reckless to claim these “stations” have revolutionized Dadaocheng, there is no doubt that the neighborhood is well on its way to becoming, dare I say it, trendy. According to the government, between 2011—the year after the URS program began in earnest—and 2015, Dihua Street welcomed 61 new businesses and saw a 65 percent increase in the usage rate of commercial buildings. Amid the shrines and dried-seafood vendors, there’s now no shortage of bookstores, single-origin cafés, galleries, and emporiums such as Artyard, which features luminous ceramics from the likes of Hakka Blue and somehow manages to incorporate Le Zinc, a cozy wine and craft beer bar that feels a world removed from the clamor outside. Yet this transformation doesn’t appear to have displaced the area’s traders and residents, who continue to go about their daily routines. As if to underline this, when I stop to peer into a shop window and inadvertently block half the sidewalk, a sweet-looking elderly lady unceremoniously swats me out of the way with her umbrella.

Encouragingly, a relative balance of commercial, cultural, and community interests seems to have been maintained even in Taipei’s larger-scale regeneration projects. Take Songshan Cultural and Creative Park, which emerged in late 2011 from the grounds of the former Japanese (and subsequently Taiwanese) government tobacco monopoly. The park is an impressive feat—especially considering the proximity of the Xinyi business district—comprising multiple city blocks of broad plazas, shimmering ponds, and lush gardens, all based on the original layout. The former factories and administrative buildings, too, have been tidied up but left largely intact, slightly dilapidated but dignified nonetheless.

Of course, they now deal in dreams rather than cancer sticks. On any given weekend Songshan’s old warehouses are equally likely to be occupied by video game launches, theatrical performances, animation exhibits, or even teddy bear trade shows. There are jam sessions on outdoor stages, giant swings for the kids, and quiet bookstores and galleries buried deep within buildings where it’s completely possible to escape the crowds, even on a weekend. The park isn’t entirely dedicated to up-and-comers: there’s a large department store operated by famed local bookstore and lifestyle chain Eslite, complete with a basement food court full of franchise restaurants. But also, just outside, is a handful of food trucks and (on the Saturday I’m there) an impromptu bazaar where nervous-looking artisans display handmade leather goods, finely carved wooden miniatures, and stuffed animals to an enthusiastic crowd of browsers.

Huashan 1914, by contrast, is decidedly more mainstream. On my way through the retrofitted former winery I spot storefronts for Sony, Twinings Tea, and Patagonia. However, there’s also a repertory cinema and several independent boutiques, as well as VVG Thinking, a restaurant and lounge by Taipei native Grace Wang’s VVG (“Very Very Good”) lifestyle brand. It’s set in a striking, almost gothic space defined by soaring ceilings and an abundance of shadowy nooks and crannies; there’s what looks like a Renaissance flying machine suspended from the ceiling and a loft full of cookbooks and kitchenware to browse—plenty to think about, in other words.

Just down the street from Huashan, I make my way to the workshop of former tenant Alex Chou, a Taiwanese-American designer who grew up in Los Angeles but was lured back to the land of his birth by prospects in the country’s manufacturing industry. He ended up designing bicycles—but not just any bicycles. His Gochic bikes are works of art in their own right, made painstakingly by hand with carefully sourced parts. Only around 100 are produced per year.

Gochic’s studio and showroom, set down a lane of old Japanese-built houses, is something of a temple for local cycling enthusiasts, who, thanks to the proliferation of bike lanes, are taking to the streets in greater numbers. “That’s the future; we’re trying to make the city better,” Chou tells me. “It’s independent brands like us that will provide the momentum.”

Gochic had shops in both Dadaocheng and Huashan before Chou moved to his current, lower-key location, though he credits these areas with helping spur a creative-industry revival in recent years. “Huashan was a perfect platform for us,” he says. “We got a lot of media attention, and we were packed every weekend—people had to line up to get in.”

He adds, “But it’s become too commercial—good for business, bad for startups. We just wish there was more support, especially cheaper space. These might be creative parks, but they’re still business-driven.”

Others in the artistic community see a relative equilibrium between commercial and creative concerns in Taipei’s development—at least, relative to other cities. Sean Hu, the curator behind Hu’s Art, which runs a network of galleries and is a regular contributor to city art initiatives, says the government may have fallen short in terms of establishing museums, but that it’s “quite friendly” when it comes to public art, making Taipei “a good platform for experimental projects.”

“The private sector here is also very willing to do something different,” he tells me. “It’s become almost trendy for companies to collaborate with artists.”

A good example of this is Leputing, a 1920s-era dormitory for Japanese civil servants in the Guting area that has been impeccably restored by the city government and conservation-minded developer Lead Jade. The main building seems transplanted straight from Tokyo, with sliding paper doors, groaning wooden floors, and windows that overlook a perfectly tended back garden. But it’s now a Japanese-accented European restaurant that’s filled to the brim for set lunches and dinners (and afternoon tea sessions) daily. It’s relatively expensive, and almost certainly profitable, but it has garnered little but praise and has brought a certain cachet to an otherwise nondescript neighborhood.

The question, with Leputing and other restoration projects, is what happens when that cachet takes over. “The government has transformed these spaces, people have become very interested, and regeneration does help the creative industry—I’m proud of the policy,” says Hu of the URO. “But I do worry about more and more people coming and attracting the retailers. What will these areas will look like then?”

These concerns are well founded because, as Hu freely admits, many smaller restoration projects are “not designed to be permanent.” If a developer swoops in and buys (or demands the return of) a newly popular place to convert it to more commercial purposes—as has happened with previous URS stations—or if the rents on a certain street climb, so be it. The URO’s bet is essentially that by the time these things happen, the positive “energy” brought to the surrounding area will be entrenched enough to remain in place.

It’s a difficult bargain that may not always pan out. But if one is willing to acknowledge that cities are at heart, restless, permanently shifting entities, unable to exist in stasis, it seems as sensible a wager as any. And there’s no doubt that in Taipei—which manages to be both ambitious and relaxed, a technology powerhouse and a place of creative opportunity and thriving cottage industries—it is already paying off.

ADDRESS BOOK

59 Qidong St., Zhongzheng; 886-2/2314-3296.

1 Bade Rd., Zhongzheng; 886-2/2358-1914.

67 Hangzhou South Rd., Da’an; 886-2/2395-1689.

Songshan Cultural and Creative Park

133 Guangfu South Rd., Xinyi; 886-2/2765-1388.

URS 127 Art Factory

127 Dihua St., Datong; 886-2/2550-6775; fb.com/urs127artfactory.

155 Dihua St., Datong; 886-2/2552 0349; fb.com/cookingtogether155.

329 Dihua St., Datong; 886-2/2550-6607.

This article originally appeared in the February/March 2017 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“The Taipei Way”).