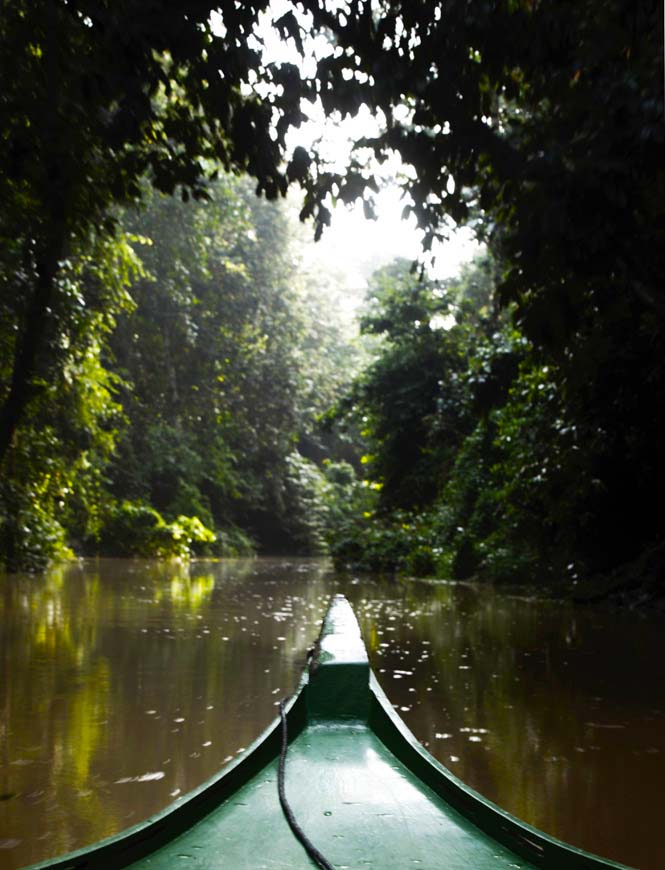

Above: A mengaris tree crowns the forest canopy along the Kinabatangan River.

From its thickly forested interior to its kaleidoscopic marine life, Sabah, the Malaysian state crowning the island of Borneo, is a natural choice for adventurous travelers

By Jamie James

Photographs by Martin Westlake

North Borneo has a bad reputation— and that’s good. Discouraged by the pirates that raided its shores and the headhunters populating its interior, the Western powers mostly kept their hands off in the colonial era. Tourism, too, has scarcely grazed the upper reaches of the world’s third-largest island, which is better known for impenetrable rain forest crawling with pythons, jungle cats, and crocodiles than for sparkling white-sand beaches. As a result of this relative isolation, the modern Malaysian state of Sabah remains a wilderness stronghold, one of the most richly endowed ecotourism destinations in the world.

My Borneo adventure began in Sandakan, which overlooks a gorgeous harbor on Sabah’s northeast coast. On the outskirts of town is the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, where some 60 to 80 apes that have been orphaned or born in captivity are sheltered until they are ready to be reintroduced into the wild. This is one of Malaysia’s most popular tourist attractions—an opportunity to come face to face with the legendary “man of the forest.” Most visitors show up for the morning feeding, when rangers bring crates of bananas and papayas to a high wooden platform. Soon, the forest canopy is alive with the thunderous crash of orangutans emerging from the trees to gorge on the fruit.

Even the most feebly talented photographer is assured of getting a great shot, with the big apes just a few meters from the visitors’ gallery. But any sense of wilderness adventure is banished by the snapping cameras and whirring camcorders. So I begged a visit to the nursery, where a ranger patiently let two of the babies climb up his body in a primate version of King of the Mountain, with his shiny bald head as the summit.

“The little ones actually prefer the girls,” Christine Jan, a 22-year-old volunteer assistant from Australia, told me later. “The men give them their injections, but we get to cuddle them and give them love.” The two-year-old orangutan draped around her neck like a fur stole seemed to beam at me in agreement.

From Sepilok, I followed the highway south to Sukau, a village on the Kinabatangan River, Sabah’s longest, which winds through the heart of the rain forest. I had traveled this road on my last visit to Borneo, 12 years ago; since then, the extent of forest clearance and the encroachment of oil-palm plantations has been astonishing, and the debate about the wisdom—ecological and economic—of Malaysia’s oil-palm boom rages unabated. Malaysia now produces 51 percent of the world’s supply, and the stakes only get higher as biodiesel fuel technology advances.

Whatever advantages they may offer, the uniform rows of stumpy palm trees, their trunks swathed in ferns, appear almost sinister, like the ranks of an invading army of triffids. Nearer to Sukau, however, the landscape took on a friendlier aspect as we reentered a mixed forest. The village itself had a genial, disheveled look, with women doing the laundry and young boys diving and splashing in the placid brown waters of the river.

At Sukau’s boat landing, I boarded a launch to the Proboscis Lodge, where I would stay for a few days. This comfortable riverside resort takes its name from the proboscis monkeys—known as bekantan in Malay—that thrive in the treetops of the great forests of the Kinabatangan. The species, unique to Borneo, appears grotesquely comical in photographs: the male has a huge, sausage-shaped nose (hence the name), a pendulous potbelly, and a permanent, flaming-scarlet erection; the females make a more discreet impression. In person, though, they are anything but risible: the biggest would be a meter tall if they stood up straight, and weigh 25 kilograms or more.

On my previous visit to Borneo, it took patience and cunning to find proboscis monkeys willing to venture into the open. This time, within minutes after we left the landing, I saw a troop of 20 of them putting on an acrobatic show, flying through the trees with careless abandon, leaping from one bough to the next and landing with a great crash that made the stoutest branches bend to the breaking point. Then a pair of rare rhinoceros hornbills, lords of the jungle’s skyways, passed overhead, and I felt myself at ease about the state of the wild nation of Sabah.

In the days that followed, I went out in the launch before dawn and after sundown—rush hour for wildlife along the Kinabatangan and saw dozens of bird species and legions of playful monkeys, a winsome civet cat munching on a mango, and a couple of baby crocodiles, only their baleful eyes and snouts poking up above the stream. Other lodge guests talked excitedly about the wild orangutans and herds of pygmy elephants they had seen. There are rhinoceros in the jungle, too, but the only glimpses of them come from motion-triggered cameras.

Inaccessible except by river, the Proboscis Lodge is remote, and many of its staff—including a flamboyant Filipino chef named Felipe, who enthuses about the fire-eating act he performs for guests when the resort is full—ply me with questions about the great world beyond Sukau. Yet even here in the protected forest, platoons of triffids have encroached. It’s illegal to clear land along the Kinabatangan for agriculture, but there they were, narrow fingers of oil-palm plantation marching down to the riverbank. No wonder the proboscis monkeys are easier to spot nowadays—their wilderness is shrinking around them.

On the way back to Sandakan, I stopped at the Gomantong Caves, a major source of edible bird’s nests. Since at least the 13th century, Chinese traders have been coming to northern Borneo to buy the nests of cave-dwelling swiftlets, which they cook in a sugary soup, one of the most prized—and expensive —tonics in traditional Chinese medicine. Intrepid Malay harvesters climb rickety rattan ladders that rise as high as 90 meters to the roof of the cathedral-like caves to cut down the nests. I arrived just after the end of one of the three annual harvests. At the ramshackle collectors’ camp outside the main cave mouth, I met a compact, wiry man who introduced himself as Dikki. A 20-year Gomantong veteran, Dikki told me that in a good year he could earn as much as US$24,000—a fortune in rural Borneo.

A wooden boardwalk has been built for visitors, to keep them from slipping and falling in the pools of watery guano deposited by the bats that share the caves with the swiftlets. I tried to keep my eye on the magnificent cavern soaring overhead, where cobalt-blue butterflies winked through light filtering down from on high, but I ended up watching my step instead, as the boardwalk, too, proved to be treacherously slick with bat excrement. I also needed to maintain a brisk pace to keep the swarming legions of guano-dwelling cockroaches from climbing up my shoes and pant legs. By the end I was sprinting, my jungle adventure more like an Indiana Jones epic than I had planned.

there must always have been a port of some sort at Sandakan’s perfect harbor; it was here that Chinese junks came to collect the bird’s nests from Gomantong and other forest products for home consumption. But the modern city was founded in 1879 by a hemp-grower named William Burges Pryer, with a staff of three men and assets consisting of three rifles, a barrel of flour, and 17 chickens. Five years later, Sandakan, then known as Elopura (“Beautiful City”), was named the capital of British North Borneo.

By the end of the 19th century, practically every speck of the Malay Archipelago had come under direct Western control, but northern Borneo was never colonized, not really. While the lower two-thirds of the island (now Indonesian Kalimantan) were ruled by the Dutch, the tiny sultanate of Brunei remained more or less autonomous, as did the neighboring British protectorate of Sarawak, run as a private kingdom by the “white rajas” of the Brooke family. The future state of Sabah, for its part, was in the hands of the North Borneo Company, a mercantile enterprise chartered by Queen Victoria in 1881. While there’s no doubt that the region was firmly in the British sphere of influence, it’s not a hair-splitting distinction; the Empire left a much lighter footprint in Borneo than in its mainland colonies in Singapore and peninsular Malaysia.

After the devastating Japanese occupation of Borneo during World War II, Sabah and Sarawak were made British crown colonies, but only briefly; in 1963 they became states of the new nation of Malaysia. Sandakan had been leveled by Japanese and Allied bombing during the war, and the capital was shifted to Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu) on the west coast. The only buildings that survived were places of worship: two Chinese temples, a mosque, and St. Michael’s and All Angels Church, built at the turn of the last century in neo-Gothic cathedral style and today featuring fine stained-glass windows commemorating the more than 2,400 Allied prisoners of war who died in Sabah during the last years of the war.

Modern Sandakan was rebuilt along utilitarian lines by its overwhelmingly Chinese residents, so while the town center has little of architectural interest, the streets of the bazaar buzz with life. So too does the traditional air kampong (“water village”) of Buli Sim Sim, a settlement of stilt houses at the mouth of Sandakan Bay. It’s an admittedly rundown district, but rich in funky, colorful character.

On a hill overlooking the city, a solid, two-story frame house, one of the few relics of old Sandakan, commands a sweeping view of the harbor—and a backward glance at the palmy days before the war. The former home of Agnes Newton Keith, an American journalist who lived in Borneo in the 1930s and ’40s, it has been restored to a sleek nostalgic shine by historians from the Sabah Museum in Kota Kinabalu. Agnes’s husband, Harry Keith, was employed by the North Borneo Company as its chief forester, a position that was interrupted by the Japanese invasion of 1942. For three and a half years, the Keiths and their infant son George were interned in Japanese concentration camps at Sandakan and later in Sarawak. Agnes Keith is best known for her prison memoir Three Came Home, which was made into a Hollywood film in 1950 starring Claudette Colbert.

Her most enjoyable book is her first one—Land Below the Wind, which takes its title from the native name for Sabah, “Negeri di Bawah Bayu,” on account of its sheltered location just south of the western Pacific typhoon belt. Published in 1939, the book is a smart, witty account of life under Company rule: “A few miles out elephants may be seen upon the road, and orangutans and gibbon apes are one jump away from the jungle, and crocodiles are caught off the customs wharf, but at four o’clock in the afternoon we are drinking our afternoon tea.” On my last day in Sandakan, I followed her example and paused for a break at a pleasant, British-owned restaurant on a verdant knoll adjacent to the Agnes Keith House, where a group of indefatigably sporty Australians were playing croquet. Plus ça change, and all that—elephants, orangutans, and crocodiles still lurk in these parts, and everything stops for tea.

A good indicator of the powerful hold that Mount Kinabalu has over the minds and souls of Sabahans is their state flag, which features the mountain’s silhouette in the upper-left canton, cobalt blue against a field of pale cerulean. At 4,095 meters, Kinabalu is the highest island peak in Southeast Asia, excluding the massifs of Papua; on a clear day, it’s visible throughout much of the state. Unlike the classic volcanic cones that dominate the tropical skyline, Kinabalu resembles a great fortress, or a crown ringed with a series of peaks.

Sabah is a land of legends, and Kinabalu has a good one. The story could have been a prototype for Madam Butterfly: Once upon a time a Chinese prince sailed to Borneo, where he fell in love with a native maiden and married her. Soon after the wedding, he returned to China on a visit home and never came back. His abandoned bride climbed the great mountain to keep a vigil for his return, where she died of a broken heart (or, more likely, the extreme cold).

Kinabalu is one of the favorite destinations in Southeast Asia for amateur climbers, because the well-maintained trail to the summit requires no special equipment or mountaineering skills. However, 4,095 meters is a serious peak, higher than most of the Alps, and ought not be undertaken except by very fit adults.

As my knees were still recovering from a trek along Nepal’s Annapurna circuit, I opted to enjoy Kinabalu’s natural wonders from a less demanding altitude. The mountain is surrounded by a national park, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000, Malaysia’s first. Kinabalu’s fertile foothills are a prodigy of biodiversity, home to rare beauties such as the Rothschild’s slipper orchid and 26 species of rhododendron (five of them endemic to the park), as well as some of the most spectacular plants on earth, from the iconic Rafflesia, billed as the largest flower in the world, to Nepenthes rajah, a huge, livid-purple pitcher plant that holds three liters of water to trap its insect prey. The park’s forest trails are popular with weekend explorers from Kota Kinabalu, less than two hours’ drive away. The Sunday afternoon I was there, the hot springs were besieged by city folk packing their children in mud; I sought refuge in the quiet, meandering pathways of the botanical garden.

Kota Kinabalu, or KK as it’s popularly known, is a pleasant enough city, though it lacks the atmosphere of venerable settlements in the Malay Peninsula such as George Town and Malacca, or of Sarawak’s riverside capital, Kuching, 800 kilometers to the southwest. Only a handful of structures remain from its days as the Company port town of Jesselton, notably the graceful Atkinson Clock Tower, built in 1905. The rest is a modern city of bland housing blocks and retail centers that looks like any prosperous community in the Pacific Rim: take away the street vendors and you might think you were in a suburb of Los Angeles. Yet it’s a fun place to spend a few days, with some good hotels and plenty to do. One wet afternoon I spend a pleasant few hours walking around the Sabah Museum, a well-curated treasure house of the state’s history and culture.

That said, the true glory of KK lies offshore. Tunku Abdul Rahman Park, one of Asia’s most beautiful natural preserves, is just a 20-minute cruise from the jetty at Jesselton Point. This cluster of coral-reef islands abounds with what the coastline of Malaysian Borneo itself famously lacks: perfect beaches. The largest is Gaya Island, still covered by intact rain forest, which has been protected by law since 1923; the other four islands were added to create a national park in 1974, named after the first prime minister of Malaysia.

Although badly damaged in the past by illegal dynamite fishing, and devastated by tropical storm Greg in 1996, the coral reefs have begun to regenerate. Today, the snorkeling and diving at TARP, as it’s called (Sabahans being even more acronym-crazy than mainland Malaysians), is the doorway to an astonishing submarine zoo thronged with brilliantly colored clownfish, sea horses, turtles, octopus, cuttlefish—anything with fins or tentacles. The water is so clear you don’t even need to jump in to get an eyeful: leaning over the end of the pier at Gaya Island, I saw a ghost pipefish, pulsing electric blue and red amid the undulating seaweed.

At day’s end, I ferried back to Kota Kinabalu to meet some friends from the Sabah Museum for an encounter with marine life of an even more intimate kind: a seafood dinner on the waterfront. Here, the visitor gets a strong sense of northern Borneo’s connection to the seas beyond—great ocean fish hang in the market, and arrays of cute handicrafts lure tourists strolling in the sunset glow. For the first time, I had a sense of KK as a lively urban place: the pubs were jumping with a brisk sundowner trade, and the open, breezy seafood restaurants were packed.

As we tucked into a superb Chinese-style fish dinner, a floorshow purported to represent the traditional dances of the region. Never mind that the performers were soft-bellied office workers in colorful feather headdresses, moonlighting as headhunters and amorous Malay princes and village maids: they were doing their earnest best to make a connection with Sabah’s primeval past. I followed them happily.

THE DETAILS: Sabah

Getting There

The Kota Kinabalu International Airport is Malaysia’s busiest outside Kuala Lumpur, servicing regional carriers like Dragonair (dragonair.com) and Malaysia Airlines (malaysiaairlines.com) from Hong Kong, Silk Air (silkair.com) and AirAsia (airasia.com) from Singapore, and Cebu Pacific (cebupacificair.com) from Manila. Sabah’s capital is also well connected domestically, with several daily flights to Sandakan, 220 kilometers to the east.

When to Go

Sheltered from the typhoons, Sabah’s equatorial climate is at its most pleasant from May to September, before the onset of the rainy season. Travelers planning to summit Mount Kinabalu should pack accordingly; come nighttime, temperatures at the top can fall to near freezing.

Where to Stay

** Just outside Kota Kinabalu, the newly renovated Shangri-La’s Tanjung Aru Resort & Spa (20 Jl. Aru, Tanjung Aru; 60-88/327-888; shangri-la .com; doubles from US$280) is a destination in its own right, with 492 rooms and suites offering views of either the South China Sea or Mount Kinabalu. Fine Sabahan cuisine and an island spa are among the attractions. (Visit its sister property, Shangri-La’s Rasa Ria on Dalit Beach, for a tour of the adjacent nature reserve, home to its own orangutan rehabilitation center.)

** The Novotel Kota Kinabalu (1Borneo Hypermall, Jl. UMS; 60-88/529-888; novotel.com; doubles from US$84) is the city’s newest—and best—in-town option.

** Downriver from Sukau village on the banks of the Kinabatangan, the cottages at Proboscis Lodge (60-88/240-584; proboscislodge.com; doubles from US$118) make a modest yet reliable base for wildlife watching and nature treks.

Originally appeared in the February/March 2011 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Back to Nature”)