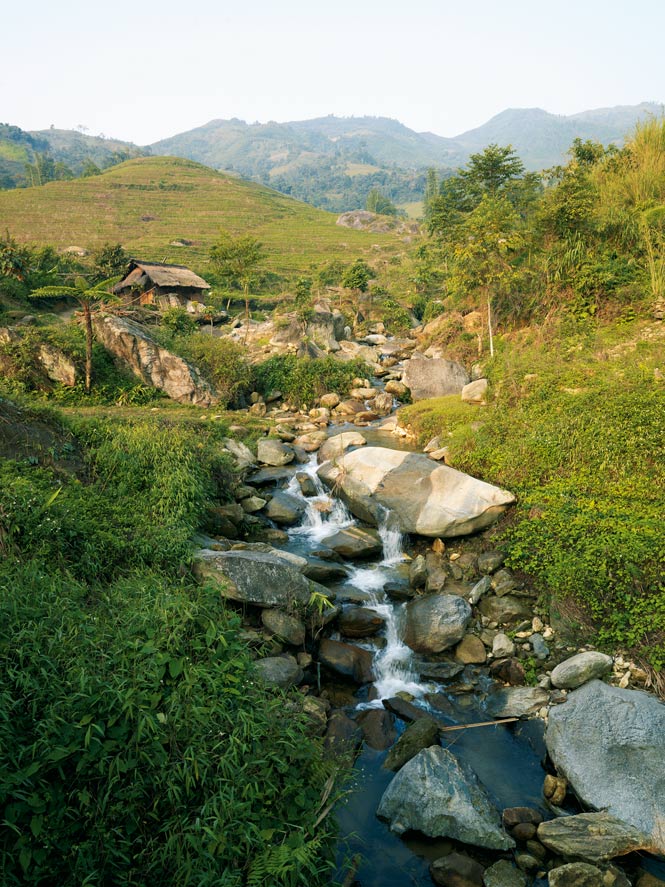

Above: The Topas Ecolodge features sweeping views of the Sapa highlands.

Editor’s note: Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg marked the end of 2011 with a trip to the Sapa region, staying at the same Topas Ecolodge pictured above and recommended below.

Cool climes and authentic hill-tribe encounters await trekkers in Vietnam’s northern mountains

By Christopher R. Cox

Beat the heat: It was an obsession for colonial-era Europeans living in tropical Asia, who every summer fled the cities of the torrid plains and malarial coastlines for salubrious hill stations scattered across the continent, from Shimla or Darjeeling in India to Cambodia’s Bokor and the Dalat Highlands of southern Vietnam. Many of these bygone refuges retain their special virtues, be they the horse-drawn carriages of Maymyo, once the summer capital of British Burma, or the abundant bird life of Fraser’s Hill on the Malay Peninsula. Then there is Sapa, an old French station d’altitude in the jumble of mountains hugging the border between Vietnam and China, which offers an unrivaled mix of ambience and adventure, climate and culture.

1. Highland scenery.

While I’ve been traveling to Vietnam for nearly 20 years, my itineraries have always concentrated on its cities and beaches. Yet a recent visit to Hanoi led me to the Museum of Ethnology, where I discovered a fascinating collection of artifacts—including fertility statues—belonging to some of the country’s 54 ethnic-minority groups who live in the mountains along Vietnam’s northern and western borders, a world apart from the plains below.

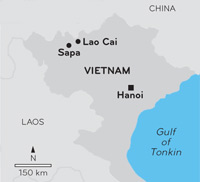

Often referred to as Montagnards, these highlanders are distinct in speech, dress, culture, history, and religious beliefs from the lowland Kinh (or Viet), who comprise 87 percent of Vietnam’s population. When I learned that Lao Cai, a modest-sized province that includes Sapa, was home to half of Vietnam’s cultural mosaic—it counts 27 different ethnic groups within its 6,363-square-kilometer confines—I determined to head for these distant, northern hills.

To get there, I take the night train from Hanoi, which chugs across the Red River’s Long Bien Bridge (a historic span designed by Gustave Eiffel) before rolling up an easy grade through the river valley. Four hundred kilometers later, we arrive at daybreak in Lao Cai City. This dreary provincial capital was leveled during a brief, bloody1979 war with China, leaving little of interest for visitors, save perhaps for a punt at one of its smoky casinos or a bowl of thong co, the horse-entrails soup that passes for a local delicacy. Fortunately, I’m not obliged to linger.

Tran Xuan Ha, my guide, meets me at the train station. He’s an enthusiastic young man who grew up in the countryside, but has forsaken the family farm for the relative bright lights of Lao Cai. “When you laugh, you say my name,” Ha offers Though a gray, miserable mist envelops the city, Ha is upbeat about the forecast for Sapa, which is situated at an elevation of 1,600 meters in the Hoang Lien Mountains, the final flourish of the Himalayan chain. With a year-round average temperature of just 15°C, Sapa’s refreshing climate certainly appealed to French colonials headquartered in sultry Hanoi and Haiphong. A military post was built on the site of an old Black Hmong village in 1903; a sanitarium followed within a decade. The French also began construction on a summer capital, planting evergreen trees, laying out hiking trails, erecting hotels and hundreds of villas.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s Sapa enjoyed a golden age, with telephone and telegraph service, potable tap water, and electricity from a modern hydropower plant. The postwar years, however, were less kind. Both the Viet Minh and French attacked the town during the First Indochina War. Sapa remained derelict for decades, and suffered badly during the 1979 dustup with China.

But in the last decade, tourism has resuscitated the once abandoned resort. According to Nguyen Ngoc Thanh, cofounder of the Hanoi-based custom-tour company that I’m traveling with, Footprint, Vietnamese visitors come to sample the town’s shops and restaurants, while foreigners use Sapa as a base camp for hikes into the mountains or for more ambitious multiday treks with overnight stays in hill-tribe villages. No matter their intent, every traveler must make the 38-kilometer drive from Lao Cai—a sinuous, one-hour ascent on a narrow road stitched into the slopes through oft-spectacular scenery, including Mount Fansipan, at 3,143 meters the tallest peak in all of Indochina. Along the route, we pass numerous Black Hmong women in distinctive midnight-blue tunics, as well as crimson-turbaned Red Dao.

In the Sapa district, these two hill tribes comprise a solid majority of the population, greatly outnumbering the lowland Kinh. On the weekends, they turn out in the town’s streets by the thousands to hawk handicrafts, textiles, and produce—and to gawk at the foreigners in their midst. Unfortunately, increased tourism and development have chased off one of Sapa’s most charming vignettes: the so-called “Love Market,” when young men and women from the surrounding hills would congregate on Saturday nights in hopes of finding suitable spouses. But no more.

3. Hmong sisters on the trail to Ta Phin.

“The Love Market was very sensitive,” Thanh says. “Minority people were very shy to sing or talk in front of outside people. It doesn’t really exist now.” Today, the best way to enjoy an authentic hill-tribe encounter is on a multiday trek. The most popular route runs south of Sapa to the village of Ta Van, through a stream-fed valley famed for its terraced rice fields. Thanh’s company takes a less-trod pathway northward through a similar landscape to Ta Phin, a valley inhabited by a few thousand Black Hmong and Red Dao.

“Ta Van is very crowded,” Thanh explains, “and the people there have changed a lot. They don’t really understand the impact of tourism. They only want more people to come; they think they will make money. They don’t care how it affects the environment.” It’s a depressing, predictable process I’ve witnessed repeatedly, especially among ethnic-minority villages in northern Thailand, where over-trekking has brought a host of social problems. Thanh has tried to mitigate visitor impact by taking small groups—no more than six people at a time—into Ta Phin, where Footprint is the only outfit offering homestays.

We set off from Sapa through a narrow valley, with a cool breeze whistling through stands of pine and bamboo and the rush of a rocky stream below. The first person we encounter is an old farmer goading a water buffalo along the track. His indigo-blue trousers and shao khua, an outer tunic made iridescent with beeswax, mark him as Black Hmong.

“The buffalo are very useful,” Ha tells me. “They can carry wood from the forest. They can plow the field. In Vietnam, we say there are three things you have to do in life: buy a buffalo, get married, build a house. Except in the city, of course—there, we buy a motorbike.”

In these mountains, where society is organized by altitude, the Hmong live at the highest elevations, growing corn and rice and gathering cardamom and orchids from the forest. The middle elevations are settled by Red Dao, who emigrated here centuries ago from Yunnan. The women of both groups are renowned seamstresses; the handiwork of Ta Phin, in fact, has a reputation that extends far beyond provincial borders. I’d first admired its intricate needlework at Craft Link, a fair-trade shop in Hanoi that stocks a variety of exquisitely embroidered textiles from this valley through a program in partnership with Oxfam-Québec and Vietnam’s Mountain Rural Development Program.

As we negotiate the rocky path into the valley, I ask Ha about item No. 2 on the Vietnamese to-do list: getting married. For a highlander, it’s an expensive proposition. A Hmong man would have to pay the bride’s family the equivalent of US$1,000 in colonial-era silver coins, along with dozens of liters of rice wine and several hundred kilograms of pork meat. Among the Red Dao, the average bride fetches about twice that amount.

“If the girl is very beautiful, they may have to pay more,” Ha says. “If she is ugly, maybe free of charge.” As we near the hamlet of Ma Cha, we pause on a rise to admire the rice fields rippling across the valley. Two Hmong women have stopped as well, sisters who are each carrying a 25-kilogram basket of goat dung eight kilometers through the mountains to fertilize the field of an in-law. Theirs is a backbreaking life: the younger sister, Khoa, married at 14 and has three children. Just 22, she looks a decade older, though I can still glimpse a flash of the beauty that once commanded a four-figure dowry.

Several hamlets later, we pick our way along a narrow pathway through the paddy to Ta Phin, where we find clusters of Red Dao women, their heads bowed under pillow-plump carmine headdresses called huong, all intently sewing. Needlework is a part of every Dao woman’s upbringing, and a set of clothing can take months to fashion. These women concentrate on a signature piece of apparel—an outer jacket, or luy dao, with a special back flap embroidered with symbols inspired by the natural world: pine trees, peach blossoms, the paw prints of tigers and monkeys.

Our homestay is with a Red Dao family about one kilometer outside the town center—a large, dirt-floored house built of sturdy wood and set amid plots of corn, cabbage, eggplant, and beans and run by Phan Man May, a 47-year-old mother of five who’s been welcoming Footprint groups for the past three years. The matriarch is quite a prize: 30 years ago, her bride price came to more than US$2,000 in silver, plus heaps of pork, rice wine, and even two kilograms of arrowroot.

I drop my gear in the adjacent dorm-style quarters, where a row of basic beds sports straw-filled mattresses and thick pillows and blankets. May then ushers me into another room with a narrow wooden tub of piping-hot water steeped with a variety of mountain herbs. After my 14-kilometer hike, the aromatic bath is a balm for my aching bones.

While I soak, I listen to the laughter of the household’s women in the kitchen area as they prepare the evening meal, chopping vegetables and stir-frying tofu, pork, and cabbage over a wood fire. During dinner, May produces a small bottle of homemade rice wine. She knocks back a slug of the searing liquid and hands me the jug.

“Good for health,” she proclaims. A half-dozen shots later, I stagger into bed. Clearly, May’s mountain moonshine is made for stronger constitutions than my own.

The household is already a hive of activity when I awake early the following morning. Looking no worse for wear, May is feeding the family ducks, while her daughters draw buckets of water from their well and her husband sharpens knives and machetes for the day’s work. May then joins her daughter, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter in embroidering panels for next season’s clothing.

We bid the family farewell and set out on another scenic trail following the contours of a river valley. Crested bulbuls and coucals serenade us from the trees, and from time to time we greet groups of farmers trudging along the path.

I’m about to remark on the timeless quality of this tableau when a trio of Black Hmong stop Ha and ask for his help. They’re having trouble working a Chinese-made Nokia mobile phone one of them has just bought in Sapa. It’s a surreal scene: traditionally clad highlanders, including a young woman sporting a full complement of silver earrings and necklaces, peering on while Ha provides tech support. The modern age is coming, even to these mountains.

THE DETAILS:

THE DETAILS:

Sapa Highlands

Getting There

Offering both coach and soft-sleeper carriages, overnight trains from Hanoi typically depart between 9 and 10 p.m., and arrive in Lao Cai City between 5 and 6 a.m. the following morning. Tickets can be arranged through most tour agencies, as can the onward transfer to Sapa, an hour’s drive away.

When to Go

Sapa’s weather is coolest from December through February, when the town can experience fog and even snow. The rainy season falls between May and September.

Where to Stay

Home to some 200 guesthouses and hotels, Sapa has lodgings to suit any budget. The 77-room Victoria Sapa Resort (8 Hoang Dieu St.; 84-20/387-1522; victoriahotels-asia.com; doubles from US$140) is one of the best options, with a chalet-style setting. A 45-minute drive south of town, Topas Eco Lodge (24 Muong Hoa, Thanh Kim; 84-20/ 387-1331; topasecolodge.com; doubles from US$85) offers a terrific escape with a view: 25 hilltop bungalows overlooking the villages of Thanh Kim and Ban Ho.

Trekking

Vietnam’s top spot for trekking, Sapa has a dizzying number of tour companies, though most follow the same itinerary to Ta Van. For something different, go with Hanoi-based Footprint (84-4/3933-2844; footprintsvietnam.com), which organizes visits to Ta Phin village for stays with Red Dao families.

Originally appeared in the October/November 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Sapa Sojourn”)

Photo credits: Top: Topas Ecolodge; 1,2: Getty Images; 3,4: Christopher R. Cox; 5. Photolibrary