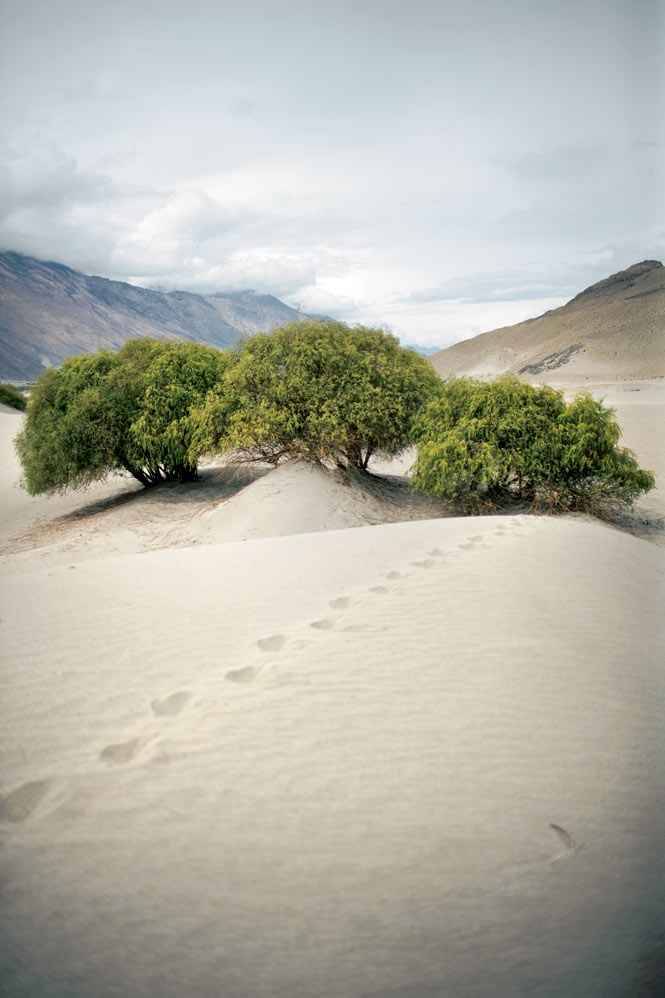

Above: Riverside scenery on the road to Ishkashim.

Remote and ravishingly picturesque, the mountain fastness of eastern Tajikistan is slowly opening to tourism. It may not be Shangri-la, but from its plunging river valleys to stark, high-altitude pastureland dotted with yurts, the so-called Roof of the World offers plenty of sublime moments for the adventurous

By Mareile Paley

Photographs by Matthieu Paley

SITTING CROSS-LEGGED on a rug in the gardens of Khorog’s Serena Inn, I pour myself another cup of tea and contemplate the view. Beyond the chrysanthemum beds and a neatly trimmed lawn framed by willows, hues of brown and beige dominate the summer landscape. The bare, gravely slopes of the western Pamir Mountains, rising away from the glacier-fed Panj River, seem dipped in caramel. After four days in the country, this strikes me as a quintessentially Tajik scene. But as I watch a man on the far bank of the river drive his donkey along a barely discernible dirt road, I remember with a start that I’m not looking at Tajikistan at all, but across an international boundary into Afghanistan.

Straddling a branch of the ancient Silk Road, mountainous Tajikistan is the smallest republic in Central Asia. It has been a cultural crossroads for thousands of years. As early as the fourth millennium B.C., lapis lazuli from the Pamir range was traded in Egypt and Sumer; since then, the territory has been crossed and conquered by Scythians, Macedonians, Hephthalites, Arabs, Mongols, Persians, and, at the height of the Great Game, Russians. In 1929, Moscow’s cartographers drew up the borders of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, a state about the size of Cambodia, with its capital in dourly named Stalinabad (now Dushanbe).

Soviet rule introduced state-run education and health care services, but smothered Tajik culture and banned the practice of Islam (the majority of Tajiks are Sunni Muslims). In 1991, Tajikistan’s newly independent government inherited a poor and divided country that was soon engulfed in a bloody civil war. The republic emerged five years later as a frail but hopeful democratic state, corrupt but safe. Before long, tourists began trickling in.

Many of them, like myself, end up on the Pamir Highway, a Soviet-built ribbon of asphalt that runs from Dushanbe into Gorno-Badakhshan, as the country’s eastern half is known. From there, it curls through the mountains before turning north to Osh in neighboring Kyrgyzstan—some 1,300 dusty kilometers in all. Officially designated the M41, it is a high way indeed, ranking among the world’s most altitudinous roads. Though I chose to skip the 20-hour haul from Dushanbe to Khorog—Gorno-Badakhshan’s rustic provincial capital—and fly with Tajik Air instead, I could look forward to spending plenty of time on the Pamir Highway in the days ahead.

Khorog is a laid-back city of 28,000 people built at the confluence of the Ghund and Panj rivers. It’s also in one of the poorest parts of Tajikistan; though spared much of the violence of the 1990s, Gorno-Badakhshan saw its collectivized rural economy falter and collapse after the withdrawal of Soviet subsidies. Help has come, however, not from far-off Dushanbe, but from the Aga Khan Development Network, whose Swiss-born founder is the spiritual leader of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam to which most Pamiri people belong. For more than a decade, the nonprofit organization has invested in humanitarian and development projects that have ranged from microfinance and ecotourism to building, in Khorog, a new university, the six-room Serena Inn, and a poplar-shaded central park.

I’m at that park now, enjoying another of the Aga Khan’s initiatives, the Roof of the World Festival. Dedicated to all things Pamiri, the monthlong event has attracted what seems like the entire population of Khorog to this leafy riverside venue. Carried by the breeze, drumming mingles with the strains of a violin as local musicians and guest performers from Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan take turns on stage. Laughing crowds gather in front of stalls selling embroidered skullcaps, felt carpets, and other handicrafts. Girls in velvet dresses hold hands and giggle, flipping their black tresses as they flirt with groups of T-shirted teenage boys. Having practiced for weeks, a local dance troupe comprising women, men, and children moves proudly in rhythmic circles on the grassy ground. Dayereh and dhol drums set the beat, while rubabs (a lutelike instrument) and ney (a high-pitched flute) add cheery accompaniment.

By the afternoon, thousands of people have descended on the park to celebrate their shared heritage. The atmosphere hums with optimism and youthful energy.

The next morning, I hire a car and driver for a weeklong tour of Tajikistan’s far east. Mir Alom is in his sixties, with a face as craggy as the mountains around us. His car, a dilapidated Russian UAZ jeep, looks to be about the same vintage. Mir assures me, however, that it is the best vehicle available for the roads ahead. “Old but tough, just like me,” he winks.

Leaving Khorog we turn south off the Pamir Highway and follow the Panj River upstream, toward the140-kilometer-long Wakhan Valley. The brown, scree-strewn slopes on both banks rise steeply, segmented by terraced wheat fields and villages of unadorned flat-roofed houses. On the Afghan side of the river, it seems that cultivation has been much more intense, reaching to the steepest cracks and corners of the inhospitable terrain. And where the Afghan fields are neat and lush, the Tajik ones seem comparatively unkempt, littered with rocks and weeds. Other potentially tillable areas lie fallow. “By the time the Russians left, we had lost so much of our traditional knowledge,” Mir explains. “We’ve since had to relearn how to cultivate a wheat field, how to build water channels. If it weren’t for the Aga Khan, we all would have starved in the 1990s.”

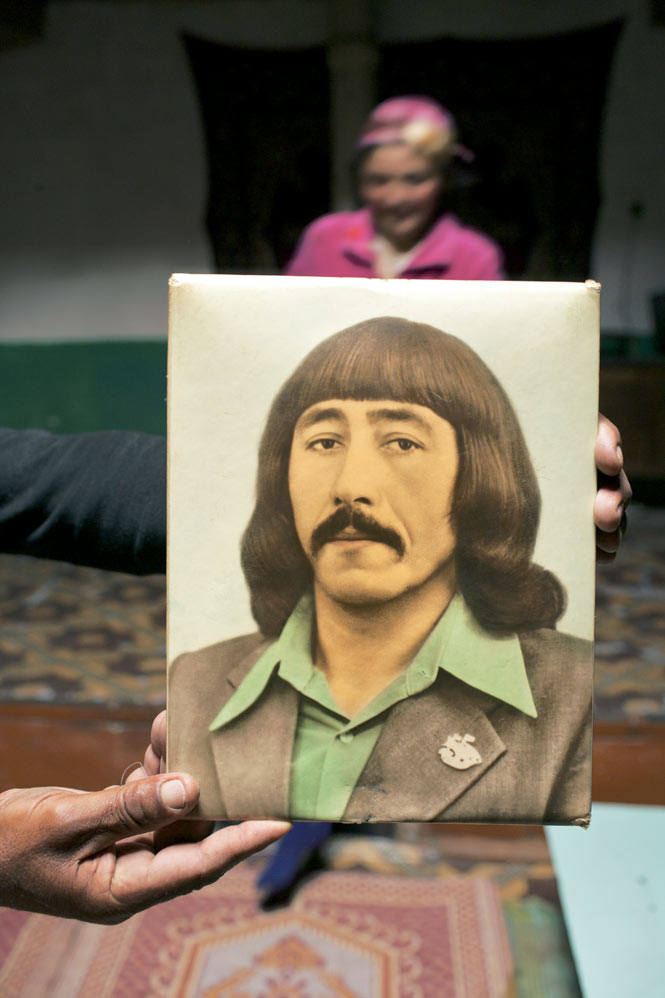

In the border town of Ishkashim, where I spot a military checkpoint at a bridge across the Panj, we stop for tea at the house of Ibrahim, an old friend of Mir. Ibrahim’s wife welcomes me as if I am a long-lost sister and within minutes the small stone-and-plaster dwelling is bustling with activity. I am beckoned to take my seat on a dais in the main room. A Russian news report flickers on a TV in one corner. The morning spread consists of steaming black tea, biscuits, a tin of butter, and some homemade cherry compote. Ibrahim then produces a round of Tajik flatbread and breaks it, carefully placing the pieces on the checkerboard tablecloth.

The house, Mir tells me, is a traditional Pamiri chid, based on a design fraught with Zoroastrian and Ismaili symbolism. A skylight in the ceiling above us is framed by four concentric wooden layers. “These represent the four elements of nature,” Mir explains, “earth, water, air, and fire. And the five pillars supporting the roof honor the five members of the family of Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s chosen heir and cousin.” In the Pamirs, it seems, a man’s home is more than his castle; it is a representation of his entire universe. It also serves as a place of prayer instead of a mosque.

For the next three days, I continue to follow the traces of ancient cultures and religions. The Wakhan Valley was once a rugged yet vital stretch of the Silk Road, linking Kashgar with the Indian subcontinent. It carried traders and pilgrims, monks and princesses, warlords and nomads, all of whom added to the eclectic mix of faces and features that define the Pamiris of today: children with blue eyes and blond hair; East European–looking beauties with olive skin and long raven hair; moonfaced men who look like they’ve ridden in from the steppes of Mongolia. Globalization came early to these mountains.

Along the way we visit unassuming, enchanting Ismaili shrines, called astans, which are dotted along the roadside behind mossy stone walls and decorated with the horns of ibex and Marco Polo sheep. I sleep in family guesthouses, and night after night watch my hosts prepare a bed out of layers of colorful quilts and mattresses, which, during the day, are neatly piled up and stacked in a corner of the room. The amenities may be basic, but the hospitality is as genuine as any I’ve encountered.

At Vrang, we stop to climb the hill behind the village, a string of curious children in hot pursuit. Perched high up the slope is another reminder of the region’s cross-cultural heritage: a sixth-century Buddhist stupa, said to be topped with a stone bearing the footprint of Gautama Buddha himself. Behind the shrine is a series of caves that once served as cells for monks and pilgrims, and later as a refuge from marauding Afghans. Whoever used these caves, they had quite the view: from this vantage, the Wakhan Valley stretches away toward the snowy peaks of the Hindu Kush, while below, the silver-gray Panj (Continued on page 118) (Continued from page 115) branches into a tracery of meandering streams that sparkle in the summer sun.

The highlight of my time in the valley is a visit to Ostoni Bibi Fotimai Zakhro—“the Holy Site of the Sleeves of Lady Fatima”—a hot spring named for the daughter of Muhammad. It’s located within a small, steaming cave overhung by dripping stalactites. Waiting my turn on the steep stairs leading down to a rickety changing room, a cackling group of older Pamiri ladies adopts me into their group. They tug my clothes and touch my hair and cover me with big towels and woolen blankets.

“You must not be cold before entering the water,” they advise. When I tell them that my husband and I are planning for a second child, the women cheer and insist that I take the first dip because, they happily inform me, Lady Fatima’s hot spring enhances female fertility.

In my mind, the epithet “roof of the World” has always smacked of false romance. Placing it somewhere between the highest peaks of the Himalayas and the dusty plains of the Tibetan Plateau, I deemed it the invention of some canny 20th-century tour operator. In fact, the term was first coined by British explorer John Wood in 1838, when, gazing across Lake Zorkul, he wrote in his journal, “we stood, to use the native expression, upon the Bam-i-Dunia or ‘Roof of the World,’ while before us stretched a noble but frozen sheet of water, from whose western end issued the infant river of the Oxus.”

I can only share Wood’s enthusiasm for the scenery as we drive through Khargush Pass, which at 4,344 meters is one of the highest points along the Pamir Highway. The Wakhan Valley is now behind us and ahead lies the high-desert plateau of the Pamir Knot, so called because it is at the intersection of Asia’s great mountain ranges: the Himalayas, the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush, and the Tian Shan.

Descending into the, our jeep gets spat out onto a wide, dusty moonscape. A turquoise-blue lake, Sasyk-Kul, resembles a discarded mirror in the flat steppe. The undulating brown mountains fringing the valley are dusted with fresh snow. They make me think of profiteroles sprinkled with icing sugar, and I laugh, suddenly realizing that I’m famished.

In Alichur, the last settlement before reaching our journey’s end at Murghab, we stop for lunch. The low adobe houses of the area rise like a bizarre assortment of building blocks connected by dirt tracks. The word restoran is painted in red brushstrokes across the length of a wall. “Very good fish!” Mir announces as he parks the car, before practically shoving me through a wooden gate into a small courtyard. Alichur, it turns out, is famous for its char, which comes from nearby Lake Bulunkul. Deep-fried until golden, the fish, I’m happy to attest, lives up to its reputation.

From here, stretching all the way to the borders with China and Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan’s far east is inhabited by ethnic Kyrgyz families. We drive past felt-covered yurts and herds of yaks, while men ride by on horses, wearing leather boots and traditional kalpak hats. It is as if we have crossed an invisible border.

Eventually, Murghab appears through the windshield. Home to some 4,000 people, it’s a lonely frontier town that began life in the 19th century as a Russian military outpost. When we arrive, women are busy collecting well water as boys dart about playing the local version of hoop-and-stick. Pretty tame stuff—but my adventures are far from over. Murghab is in the midst of its annual At Chabysh horse festival, which is held on the plains outside town.

When Mir drops me at my guesthouse, Jacqueline Ripart is there to greet me. A wiry Frenchwoman, Ripart runs the Kyrgyz Ate Foundation, an NGO dedicated to saving the Kyrgyz horse—a small, agile breed that has almost been crossbred out of existence—as well as the Kyrgyz equestrian traditions. The At Chabysh festival is one of her showcase projects.

“Welcome to Murghab and our festival,” she says. “We have already selected a horse for you. I hope you can ride?”

The Details:

Tajikistan

Getting There

From Southeast Asia, the most direct access to Tajikistan is via the United Arab Emirates. Somon Air (somonair.com), Tajikistan’s first private airline (and the first to offer an online booking system) flies once a week between Dubai and Dushanbe, the Tajik capital. Tajik Air (tajikair.tj) operates a daily service between Dushanbe and Khorog. Visas are required for most nationalities, as are travel permits for entering Gorno-Badakhshan.

When to Go

Tajikistan’s winters are harsh; aim to visit in spring or autumn, on either side of the muggy summer months.

Where to Stay

** Dushanbe’s top property is the Hyatt Regency (26/1, Ismoili Somoni Prospekt; 992-48/ 702-1234; dushanbe.regency.hyatt.com; doubles from US$250), a downtown business hotel with 202 rooms and suites, ample dining and entertainment options, and a good spa.

** In Khorog, the best of a meager handful of options is the Serena Inn (992-35222/3228; serenahotels.com doubles from US$170), which takes its design cues—wooden ceilings, stone pillars—from traditional Pamiri houses. It also has a splendid setting on the banks of the Panj River. Be sure to book well in advance, as there are only six rooms.

** To connect with homestays in the Wakhan Valley and beyond, arrange a tour with a local travel agency like Dushanbe-based Hamsafar Travel (992-372/280-093; hamsafar-travel.com), which can also arrange guided transportation.

Originally appeared in the December 2010/January 2011 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Passage to Pamir”)