That afternoon on Yasothon’s main drag, Jangsanit Road, I count no less than eight bandstands, all with concert-sized speaker stacks blaring out mor lam songs. The beat is relentless, propelled by either traditional instruments or electronic keyboards and drum machines.

Mor lam started out as Laotian folk music, played on pan flutes and three-string guitars. These days, however, it often sounds like a mixture of dancehall reggae, hillbilly rock, polka, call-back choruses, and hip-hop verse. Still, the genre is firmly grounded to its story-telling roots and rural sensibilities. The subject matter tends to center on the plight of disenfranchised farm folk: their flight to the city to find work, and the heartbreak and homesickness that follow.

It can be an infectious sound, one that inspires a steady sway that can transmogrify into a wild, windmilling dance. The rum or whiskey that sits on almost every table expedites this process. By 2 p.m., most of Yasothon is tipsy. And then the parade begins.

Above: Yasothon’s Bun Bang Fai parade features everything from traditional marching bands and dancers to comedy troupes.

Katoey “ladyboys” lead the festive charge. They march holding portraits of Thailand’s beloved king and his family, or sashay about plucking banjo-like phins and striking poses. Processions of traditional female dancers follow. Their hair is pinned in tight, shiny buns, and their hands brush elegant strokes on an invisible canvas.

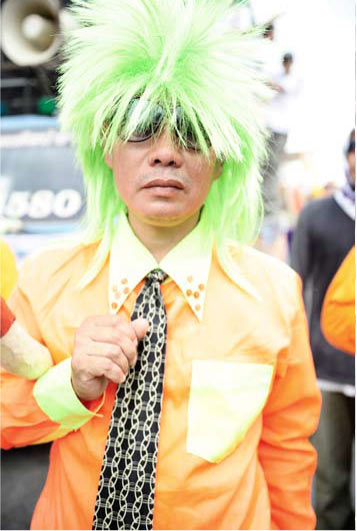

After this comes a legion of floats. These display old-style bamboo rockets decorated with the heads of naga serpent deities, some of which are rigged with hoses to spit water on the crowd. Then there’s the comedy troupe. An older gent ambles down the street in a bright yellow wig and a loincloth. He’s smiling and waving a red phallus-shaped scepter—a vestige of the festival’s roots as a fertility rite. Behind him, a mud-smeared caricature of a drunken peasant pushes a plow pulled by a papier-mâché water buffalo, careening into spectators as he goes. Dirty jokes are shouted from the floats, and the crowd erupts in laughter.

The parade climaxes with the appearance of an enormous gai baan, the free-range “house chickens” that are so close to Isan’s culinary heart. Behind it, on the back of a flatbed truck, is a jaunty re-creation of a village scene, complete with banana trees, thatched huts, and real chickens spattering above a cooking fire. The float’s participants dance about the flames, drinking more rum as charcoal smoke curls around them. And with that, the revelry begins in earnest.

Above, from left: An elaborately coiffured parade dancer; a float featuring ceremonially garbed locals atop a papier-mâché horse; a katoey performer playing a double-necked phin; local families gather street-side to watch the Bun Bang Fai parade.

If you decide to go to Yasothon, know this: there is no escaping the hospitality, and for three days during Bun Bang Fai the party never stops. It goes on in places like the parking lot of my hotel, where a local family has set up a stage and is singing away like a traveling band. It continues on curbsides, on the back of pickup trucks, in restaurants, and then later at the boisterous Rocket Pub, the only real bar here. It trails off late into the night like a final verse of mor lam, and as the dawn breaks, it all begins again.

Above from left: A cloud of smoke from a sky-bound rocket rolls across the launch field; a festive fashion statement; spicy pork larb salad; Jangsanit Road on parade day.

For three days, the people of Yasothon give themselves over to the pursuit of sanuk, or fun, and I find it in full swing at Mong Saap. Bruno Prasit’s roadside eatery might just be the best restaurant in town; it’s certainly the most famous. His two dogs, Namkaeng (“Ice”) and Soda, pad about the wide wooden terrace between tables of leathery tattooed bikers. Occasionally, a cow wanders by. Bruno, now in his fifties and sporting a long gray ponytail, played the drums for over 20 years in Phuket and Pattaya, and his drum kit—built around the handlebars of a custom chopper—adorns the front of the restaurant. The ink on his left bicep depicts a human skull sprouting antlers and eagle wings. “My wife made that. She’s a tattoo artist,” he says with a smile, pointing to the sturdy woman who also cooks the soulfully spicy food here.