It seems unimaginable, but with as many as 35,000 African elephants being slaughtered each year by ivory poachers, the future of the world’s largest land animal is once again in jeopardy. A new book by photographer Nick Brandt—the final volume in a trilogy documenting the disappearing wildlife of East Africa—makes plain what’s at stake: nothing less than the survival of one of the most intelligent species on the planet

By Christi Hang

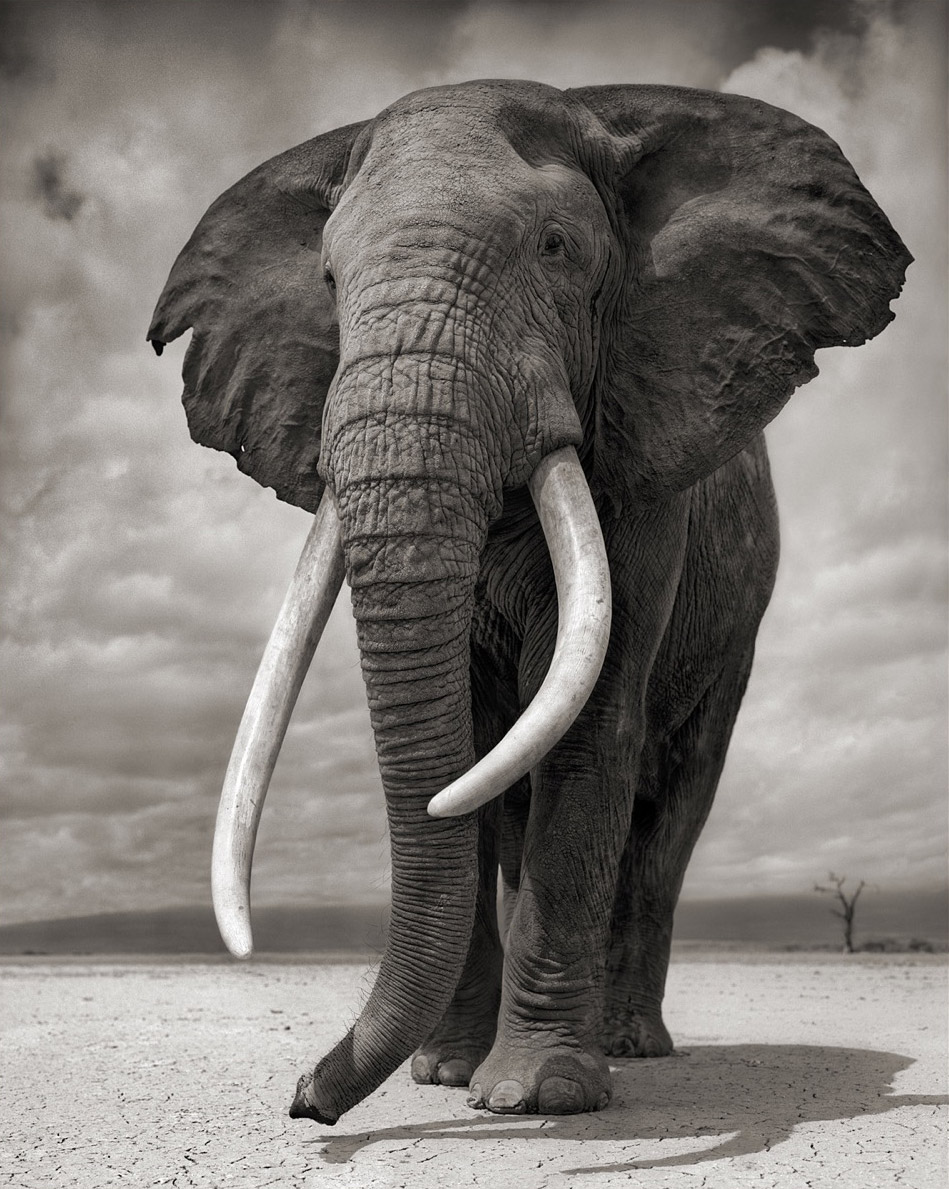

“Every time I photographed an elephant in the past few years, I wondered if this would be the last time I would see him alive,” says Nick Brandt, a British fine-art photographer who has been documenting East African wildlife for more than a decade. “It seems almost impossible that an animal whose tusks are worth literally hundreds of thousands of dollars in China can move safely, unharmed, across a land so filled with poverty-stricken people. Sometimes it seemed like a miracle when a tusker reappeared after months of no sightings.”

The sad fact is that Africa’s elephants are being slaughtered at rates not seen since the 1980s, when ivory hunting was rampant across countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. A worldwide ban on the ivory trade, enacted in 1989 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), was for a time effective, causing ivory prices to plummet and allowing elephant populations to begin to recover. But today, a boom in illicit ivory trafficking is once again threatening to wipe out elephants, fueled by surging demand from Asia, and in particular China, where the so-called “white gold” now sells for as much as US$1,300 per pound on the black market. And poachers have never been better organized or equipped, using helicopters, GPS gear, night-vision goggles, and automatic weapons to hunt their prey. By some estimates, as many as 35,000 African elephants were killed in 2012—almost 100 per day—a figure that approximates 10 percent of the entire population.

Some of these lost giants appear in Brandt’s new book, Across The Ravaged Land (Abrams; US$65), the final part of a photographic trilogy that chronicles the changes and challenges to the wildlife of East Africa. Brandt’s images—startlingly intimate portraits shot on black-and-white film without the benefit of zoom or telephoto lenses—are all the more haunting for the fact that many of their subjects no longer exist. In an accompanying essay, Brandt discusses the fate of several elephants he came to know over the past 12 years, such as 49-year-old Igor, who was so trusting that the photographer could come within a couple meters of him; and Qumquat, a matriarch well known in Kenya’s Amboseli National Park, who until recently led a herd that included her daughters and several calves. Igor’s tusks, we learn, were “hacked out … from his face” by poachers in 2009, a similar fate to what awaited Qumquat and her family the day after Brandt photographed them in October 2012. “In one hellish afternoon, three generations of her family were exterminated.”

Elephants, alas, are not the only at-risk animals in Africa, nor are they the sole subject of this 120-page book. Brandt has also included portraits of lions and other savanna species that are threatened by poachers in East Africa because their body parts are thought to be magical, medicinal, or symbolic of status. Writes Brandt, “Viewing the steep downward slope on the graphs, it means this: at the current rate of slaughter, there will be no elephants, no lions, no cheetahs left in the vast expanse of the African continent within fifteen years.”

A darker, more desolate tone pervades Across The Ravaged Land than in the previous two volumes of Brandt’s East Africa trilogy, On This Earth and A Shadow Falls, the titles of which form a sentence when read in order. But rather than just a bleak possible epitaph for Africa’s wildlife, the book and its author offer a call to action. Brandt, who originally came to Tanzania in 1995 to film Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” music video and fell in love with the African landscape, eventually found himself compelled to do more than document the destruction; he teamed up with conservationist Richard Bonham in 2010 to create the Big Life Foundation, a conservation group based in the 8,000-square-kilometer Amboseli ecosystem that borders Kenya and Tanzania in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. The foundation currently has 315 rangers, 31 outposts, and 15 patrol vehicles, and works with local communities to find new ways for them to peacefully coexist with wild animals. Big Life, says Brandt, is the only organization in East Africa running coordinated cross-border anti-poaching operations, and it continues to make strides: this year, it extended its reach to the Tarangire-Manyara wildlife corridor of northern Tanzania, where large numbers of animals, from giraffes to zebras, were being gunned down for the bush-meat markets of Arusha and beyond.

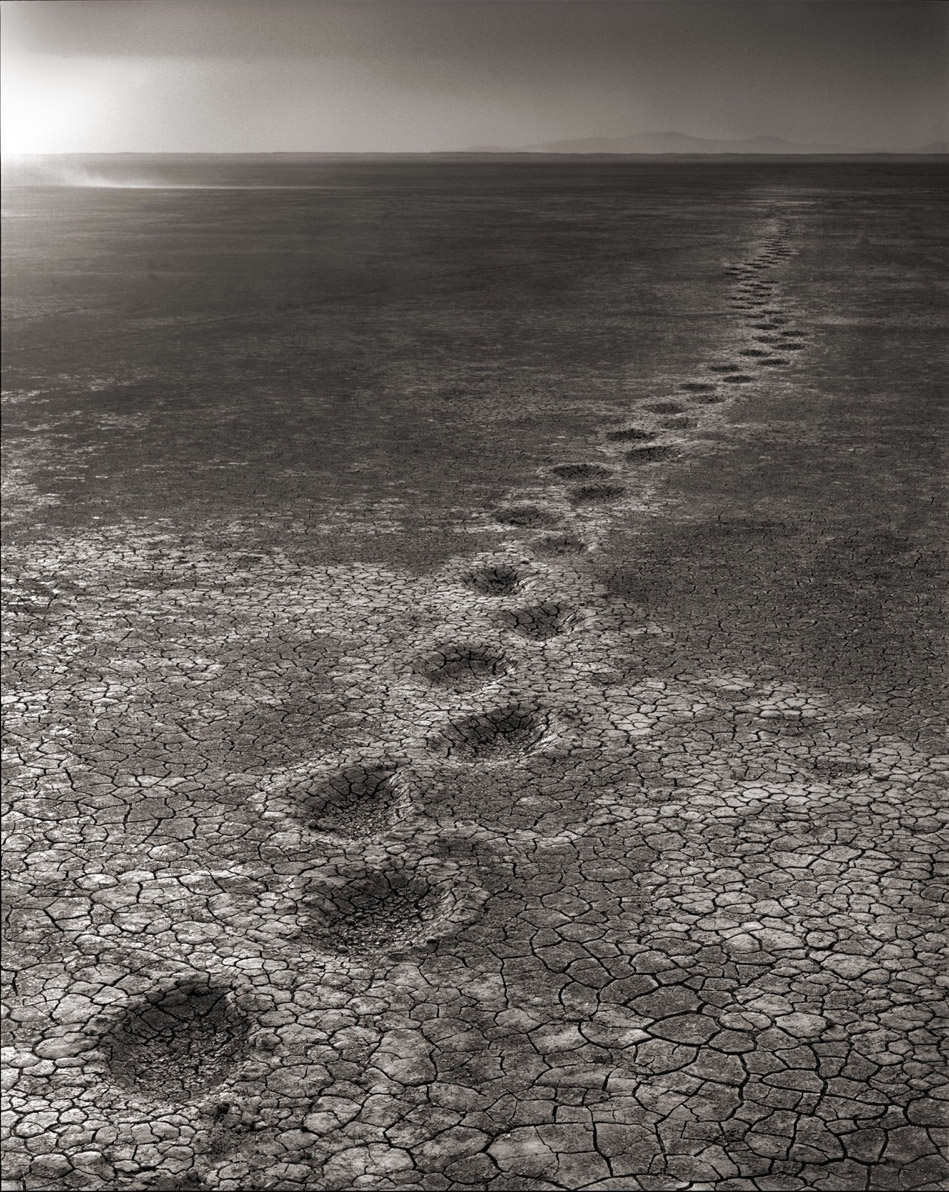

Some of Big Life’s rangers are portrayed in Across The Ravaged Land, the first humans to make an appearance in Brandt’s books. In the photograph on the previous page, a line of 22 rangers is pictured receding across the cracked earth of an Ambolesi plain, each with a pair of tusks from Kenya’s stockpile of confiscated ivory. The tusks in the foremost pair, giant scimitars of ivory weighing more than 55 kilograms each, would fetch close to half a million dollars in China today, Brandt notes.

“I’ve never seen elephants with tusks anything like that size,” the photographer writes, “and now, I never will. They are all gone, dead, mostly killed by man … [But] until sufficient national and international pressure is exerted to implement truly meaningful bans on the trade in animal parts, we will have to continue to choose which battles we stand a chance of winning, and those we know that we cannot.”

For more information about how to get involved with Big Life Foundation’s conservation efforts, visit biglife.org.

This article originally appeared in the December 2013/January 2014 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Africa Without Elephants?”)