Above: Early-morning mist hangs over the Hulikal Ravine, a view enjoyed from the Kurumba Village Resort outside Coonoor.

While not as sedate as they were a generation ago, the cool Blue Mountains of Tamil Nadu are still a very special place, as one returning devotee discovers between visits to tea estates and hill stations

By Shoba Narayan

Photographs By Martin Westlake

Residents of the Nilgiris will tell you that the highlands they call home have good vastu—a harmonious alignment of energies that sets them apart from anywhere else in India. I for one have long been mesmerized by the mountains’ ethereal beauty. As a child, I used to sit on the porch of my grandparents’ house in the plains of Coimbatore and stare up at the mist-shrouded peaks for hours. To a 10-year-old schoolgirl, the Nilgiris—which in Sanskrit means “blue mountains”—seemed otherworldly. My grandma used to say that they sent out positive vibrations; that gazing at them could soothe the wounded soul.

Covering an area of roughly 2,500 square kilometers in Tamil Nadu where the state’s borders rub up against Kerala and Karnataka, the Nilgiris are but a fraction of the Western Ghats, the mountain range that separates much of India’s west coast from the dry and dusty Deccan Plateau. With a population of fewer than 800,000 people, the district is practically uninhabited compared to the rest of the country.

I vividly recollect family trips to the Nilgiris during my school holidays. We’d pack into my granddad’s battered blue Ambassador sedan and brave the two-hour drive north, navigating steep roads that twisted through the folds of windswept hills. As we climbed, we’d pass through tiny whitewashed villages where kids with neatly parted hair and shining faces trudged uphill to school. I’d wave to women picking leaves in the undulating, emerald-green tea plantations, and press my nose against the car window as we motored past estates named in colonial times by homesick Scottish planters: Glendale, Glenburnie, Adderly. We’d stop to picnic by the side of the road, on grassy verges where mushrooms grew wild and thrushes and flycatchers swooped overhead. I wouldn’t want to leave.

Returning to the Nilgiris a quarter-century later with such nostalgic memories, I find that life in the hills has changed. On the plus side, there are now organic farms and gourmet tea lounges, and shops stocked with artisanal Camembert and chocolate truffles. But there is also a lot more traffic than I remember, more sad concrete buildings, and too many tourists to count. And yet, the mountains have retained much of the magical, sleepy allure that I first fell for all those years ago. And they’re still blessed with the keen, salubrious climate that encouraged the British to build hill stations here in the first place—an atmosphere immortalized by the great Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson as “sweet half-English Neilgherry air.”

On this visit, my journey begins not in Coimbatore but 340 kilometers to the northeast, in Bangalore (officially Bengalaru) where I now live. But in keeping with tradition, I’ve made it a family trip, bringing along my daughters, 12-year-old Ranjini and 7-year-old Malini. I’m hoping to give them a taste of the cool Blue Mountains that I remember as a child.

Surrounded by tea plantations at the head of the Hulikal Ravine, Coonoor is the second-largest town in the Nilgiris. Once the sleepy sister of Ooty—dubbed “the Queen of Hill Stations” by Jawaharlal Nehru—Coonoor has come into its own in recent years, and is now the retreat of choice for Bangalore’s beau monde. Although guesthouses and homestay cottages dot the highlands, a number of my wealthier compatriots have taken more permanent digs, snapping up vast estates and building luxurious villas—and driving up real estate prices in the process.

The British began their foray into this hitherto untamed region in 1799, after the defeated kingdom of Mysore was forced to surrender much of its territory to the East India Company. Even then, exploration of the mountains proved arduous. It would be another 20 years before a surveying party led by the chief officer of Coimbatore, John Sullivan, scaled the Nilgiris’ eastern plateau. Near the present-day township of Kotagiri, they discovered a tableland of “extraordinary grandeur and magnificence: everything that a combination of mountains, valleys, wood and water can afford.…” Sullivan immediately commissioned the building of a bridle path into the hills, and in short order became the highlands’ first European resident. By 1822, he had discovered the fertile basin around what is now Ooty, founding what was to become the greatest hill station in southern India.

Today, most visitors to the Nilgiris pretty much follow Sullivan’s route, either in cars up curving ghat roads or as passengers aboard the Nilgiri Mountain Railway’s century-old “toy train,” with its smoke-belching steam engine and royal-blue compartments. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, the line runs 46 kilometers from the town of Mettupalayam, at the foot of the Nilgiris in Coimbatore, on a rack-and-pinion system that pulls its locomotive up the steep gradient to Coonoor, 1,858 meters above sea level. For the onward journey to Ooty, the railway employs a prosaic diesel engine—not quite as romantic an experience, but equally scenic.

As we’re approaching from the north, the train is not an option. Instead, we settle in for a seven-hour drive from Bangalore to Coonoor through the magnificent Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Spread-eagled across the borders of Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, the reserve encompasses 6,000 square kilometers and six national parks. As you might expect, its forests and grasslands abound with wildlife; there are more than 100 species of mammals—including elephants and the rare, mountain goat–like Nilgiri tahr —as well as countless birds and a mind-boggling array of plants and ferns. These slopes are also home to the iridescent neelakurinji flower, which blossoms just once every dozen years and turns entire hillsides into a blanket of indigo: hence the Blue Mountains.

Our first night is spent in the middle of all this, at the Kurumba Village Resort, which lists its address as being “between the fourth and fifth hairpin bend” on the Ooty–Mettupalayam Road. Having been in the car for the better part of the day already, I’m cursing myself for picking such a remote location to bed down; the extra 14 kilometers from Coonoor to Kurumba takes an hour to navigate. But my misgivings evaporate as soon as we arrive at the eco-lodge. From its dining room, all we can see is pristine forest, devoid of buildings and even telephone poles—a rare sight in India. I linger over drinks until dusk swallows the view.

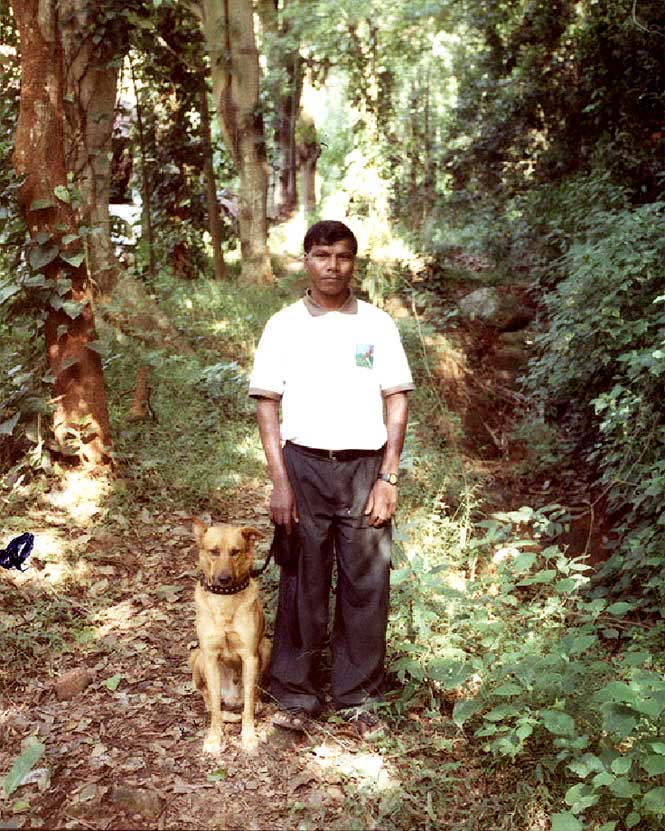

The next morning we set out to explore the hills with a team from the resort: a garrulous naturalist named Srinivasan, a silent Irula tribesman, and a wolf-size tracking dog. “If the dog stays ahead, you know all is well,” Srinivasan tells us. “If he smells an elephant or a tiger, he will come back with his tail between his legs. The dog we had before this one was eaten up by a leopard!” The girls find all the talk of exotic animals exciting and forge on ahead of me. I quickly forget my own concerns; the countryside is a stunning distraction. Herbs scent the air, and tinkling waterfalls spill over rocks and cool our feet.

Back at the resort, afternoon tea is waiting. We feast on freshly baked cakes and bhajjias, fritters made with sliced onions and potatoes. There’s also Mysore bonda, a type of spicy coconut ball, deep-fried and served with peanut chutney. And tea, of course—a robust orange pekoe. We lie back on the lawn afterward and stare up at the mountains. Whispering in my ear, Ranjini says that it feels like floating in a hammock in the clouds.

People are drawn to the Nilgiris for all manner of reasons: to escape the heat, to escape the big-city crowds, to get back to nature. For Mansoor and Tina Khan, it was a combination of all three that persuaded them to pack up life in Mumbai and move to Coonoor. It was an easy decision, Mansoor tells me, made easier by the educational opportunities available for their children. Unlike many small mountain towns, Coonoor and Ooty have world-class schools like St. Hilda’s, Breeks, and Hebron. Many Indians choose to send their kids to boarding school here, seeing a stint at the Lawrence School in Lovedale, for example, as the subcontinental equivalent of Eton or Exeter.

Tina is an accomplished cheesemaker and sells a variety of organic cheeses under the brand Acres Wild, which is also the name of the Khans’ family farm. Made with milk from hybrid Jersey and Holstein cows, Tina’s cheeses range from a creamy feta and piquant ricotta to smoky hard cheeses, gooey Camembert, and flavorful herb and pepper molds.

As I sample a caraway-spiced Gouda in the Khans’ dining room, Mansoor informs me that their neighbor is a chocolatier. Who can resist? We stop by to pick up a box of silky truffles to tide us over on the drive to our lodgings for the night, the Gateway Hotel in residential Upper Coonoor. Owned by the Taj group, the hotel was once the priory of the adjacent All Saints Church, although it feels more like a planter’s bungalow than a monastery. I leave the kids playing volleyball on the lawn and wander over to the church, a pretty Gothic structure with stained-glass windows and a turreted belfry. In the cemetery outside, the sexton shows me graves marked with quintessentially English names like Frost and Stevens.

I inspect the epitaphs until daylight fades and the evening air turns chill, then bolt back to the cozy bar at the hotel.

The next day we take to Coonoor’s gourmet trail once again. Sandeep Subramani is the amiable owner of the Tranquilitea tea lounge, located in an old bungalow on the verge of Sim’s Park, a sprawling botanical garden planted in 1874. We sit outside sampling freshly brewed infusions and nibbling on home-baked walnut bread and cinnamon cookies. Subramani kindly offers to take me to the nearby Glendale Tea Estate, which is owned and managed by his friend Udayakumar.

Born into the tea business, Udayakumar has the deliberate gait of a man who knows that the world will wait for him. His company, Glenworth, has plantations in Sri Lanka and across the Nilgiris, and is today one of the largest and most forward-looking businesses in the area. Udayakumar’s staff have access to a hospital and a child-care center, and his tea pickers receive a generous medical allowance that covers everything from common colds to open-heart surgery.

After touring the 450-hectare estate and factory, we sit with Udayakumar for a tea tasting. I pretend to understand the jargon: first flush, silver tip, CTC (crush, tear, curl), BOPD (broken orange pekoe dust). I sip, swirl, and spit dozens of brews, letting the fragrant, smooth, and robust flavors roll around in my mouth. My host tells me that although Nilgiri teas, first planted by the British in the 1860s, aren’t as well known as those from Darjeeling, they’re often more flavorful. He says that one of his black teas recently fetched US$600 per kilo at auction in Las Vegas. “The cognac of tea,” he calls it.

From Coonoor, we cross the Ketti Valley and follow the winding road to Ooty. Perched at an altitude of 2,240 meters amid stands of mature cypress and yet more tea plantations, Ooty (which is short for Ootacamund, though its official name today is Udhagamandalam) is the capital of the Nilgiris district, home to some 90,000 people. Built around an artificial lake, it served until India’s independence as the summer retreat of the Madras Presidency, a colonial province that incorporated present-day Tamil Nadu, northern Kerala, and parts of Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and Karnataka. Alas, Ooty seems to have lost some of its charm with the influx of day-trippers in recent years. In the center of town, a lone policeman is futilely attempting to direct traffic. Horns honk, cows walk absentmindedly across the street, tourists drop litter on the roadsides. After the quiet pulse of Coonoor, Ooty seems raucous and unruly.

We ensconce ourselves in Kluney Manor, a handsome 1828 villa set high above town overlooking the Ooty racecourse. Its wrought-iron beds, wood-paneled rooms, and manicured lawns are suitably quaint, but tonight being my birthday, we elect to dine at another slice of Victoriana, the Savoy, Ooty’s poshest hotel. Originally built as a school for European children, the main building dates back to the hill station’s earliest days, and is surrounded by carefully tended flower beds and tile-roofed cottages. I wander the corridors gazing at the lithographs and taking in the period features in the rooms. A fabulous barbecue dinner in the garden ends with cake and numerous renditions of “Happy Birthday” sung in warbling falsettos.

The next morning, we explore Ooty’s Botanical Garden, a 22-hectare park laid out in 1847 by the Marquis of Tweedale, then the governor of Madras. With its manicured lawns and rose gardens, ponds and pergolas, it’s a pleasant enough spot; but by 10 a.m. it’s quickly filling up with other visitors, so we make our way to the Honey and Bee Museum. Located near the old Ootacamund Club—said to be the birthplace of snooker—this low-key museum is run by the Keystone Foundation, a grassroots NGO founded a decade ago in Kotagiri. It pays homage to indigenous honeybees and the hill tribes who harvest them, but more fascinating is the Green Shop on the ground floor, which is dedicated to selling tribal produce and crafts. The mountains’ original inhabitants are still integral to the Nilgiris community. The Todas are pastoralists, known for their hand-woven shawls and buffalo-milk products; the Badagas cultivate the land and have a bard-like tradition of folk music that can be heard wafting around the mountains; the Kotas are renowned for their pottery; and the Kurumbas gather wild honey and herbs. Recognizing a good excuse to shop when I see one, I dutifully stock up on jars of bitter honey, eucalyptus oil, and beeswax balm.

On our last day, we make a detour to the lakeside village of Avalanche, named, somewhat dauntingly, after an 1823 landslide. On the map it doesn’t look far: a mere 28 kilometers south of Ooty. But the roads are narrow and tortuous, and it takes us two hours to get there. The alpine scenery offers ample compensation. We drive through forests of oak and cypress, passing fields of rhododendrons and wild orchids. This mountainous backcountry looks more Swiss than South Indian, and by the time we stop to eat at a homestay called Tiger Hill, I’ve almost convinced myself that we’ve been magically transported to Interlaken.

After lunch, the highlight of which is a curry made with young bamboo shoots, we walk off our meal with a hike around the looming twin peaks of Kudikkadu and Kolaribetta. It’s a strenuous climb, and we’re exhausted by the time we reach the lookout, but again our efforts are rewarded by the views.

Back in Ooty, I have one last appointment: I’m to meet my mother-in-law’s pen pal, Indu Mallah, a respected writer, literary critic, and activist for the Badaga community. Mallah welcomes me into her gracious home and chats about the book club and the poet’s society she oversees in town. But as she talks about upcoming readings and book launches, I again wonder whether the sleepy Nilgiris of my childhood haven’t entirely vanished. Mallah, ever the poet, sighs and reminds me of what’s important, echoing what my grandmother used to tell me all those years ago: regardless of what changes time has brought to these highlands, they possess a special, immutable aura. The Nilgiris will always be a source of regeneration—not once every 12 years like the blossoming of the blue neelakurinji flower, but every time you visit.

THE DETAILS:

Tamil Nadu’s Blue Mountains

Getting There

SilkAir (silkair.com) operates three flights a week between Singapore and Coimbatore, from where it’s a two-hour drive to Coonoor. Singapore Airlines (singaporeair.com) and Dragonair (dragonair.com) fly to Bangalore from Singapore and Hong Kong, respectively, with the drive to Coonoor taking seven hours.

When To Go

The summer months (April to June) are the most pleasant, although they coincide with school holidays and see the Nilgiris overrun with tourists. December to April is cooler and quieter.

Where To Stay

No two rooms are alike at Gateway Hotel (91-423/ 223-0021; thegatewayhotels.com; doubles from US$82) in Coonoor, within walking distance of Sim’s Park. Kurumba Village Resort’s (91-944/399-8886; kurumbavillageresort.com; doubles from US$185) cottages are built on stilts to take advantage of mountain views.

Kluney Manor (91-423/244 7336; kluneymanor.com; doubles from US$51) in Ooty has spacious rooms with open fireplaces, wooden floorboards, and poster beds. The colonial-style cottages at the Savoy (91-423/ 244-4142; tajhotels.com; doubles from US$82) also have period furnishings as well as views over flower gardens.

What To Do

The Keystone Foundation (keystone-foundation.net) runs the Honey and Bee Museum in Ooty, providing insights into honey harvesting in the Nilgiris. On site is one of its three Green Shops—the others are in Coonoor and Kotagiri —where you can buy locally produced handicrafts.

In Coonoor, stop by Tranquilitea (91-944/384-1572; tranquilitea.in) for flavorful infusions and home-baked snacks. Tour Glendale Tea Estate (91-423/220-6279; glendale-tea.com) and Acres Wild (91/9487-068-898; acres-wild.com) to stock up on organic teas and cheeses.

Train buffs won’t want to miss out on a scenic ride aboard the Nilgiris Mountain Railway (indiarail.gov.in), a century-old steam engine that runs between Connor and Mettupalayam.

Originally appeared in the February/March 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“A Higher Calling”)