Above: A portrait of the late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini in Esfahan.

The great Persian cities of Shiraz and Esfahan reveal a land rich in history and hospitality

By Jini Reddy

I am the sole customer in a beauty salon in Shiraz, and I’m suddenly feeling overdressed. After the sea of manteaus and chadors outside, the sight of seven bareheaded cosmeticians wearing skinny jeans and skimpy tank tops comes as a shock. And I’m dumbstruck by 22-year-old Mina, who is sporting a Western-style bridal veil and makeup that falls somewhere on the cosmetics spectrum between Goth and geisha. “In private, we express ourselves as we like; there are no restrictions,” she says as she begins to powder my cheeks with blush.

This is when it occurs to me that the Islamic Republic of Iran is probably a very misunderstood place—a tightly controlled society, to be sure, but not joyless, not downtrodden, and certainly not inhospitable. Or at least that’s how it seems in Shiraz. Set in a green upland basin 920 kilometers south of Tehran, this storied city is known for its liberal, relaxed atmosphere. It has flourished as a center of the arts since the 18th century, when the enlightened Persian ruler Karim Khan Zand made it his capital. These days, Shiraz also has a college-town feel, thanks to the presence of one of Iran’s best universities. Then again, in a country where 70 percent of the population is under the age of 30, youthful vitality is not hard to come by.

Sauntering down Zand Avenue, a busy main drag lined with sweets shops, cinemas, and booksellers, I pass gaggles of young men and women. The latter stride alongconfidently, chic in their silk headscarves and figure-hugging tunics. They have a feisty, assured air about them, which I find surprising given the restrictions on dress and social behavior ushered in by the Islamic revolution of 1979. And they are eager to reach out to the few foreigners in their midst. “Much is illegal in the Islamic Republic,” one woman tells me with a defiant shrug. “Parties, holding hands, satellite TV. But we don’t care, we still do these things.” The men, on the other hand, wear a mild-mannered, melancholic look. Conscious that I am a female, they keep their distance. Still, hospitality is hardwired into the Iranian psyche. “Welcome,” they say, softly, as we pause at a traffic light.

The colorful, frenetic Bazar-e Vakil is located in Shiraz’s old eastern quarter. Here, I wander past fabrics and colorful Qashqai tribal rugs until I reach a sweets stall. Iranians have a weakness for confectionery, a trait I happily share, and on the advice of the vendor, I stock up on slices of gaz (pistachio nougat) and a brittle caramel candy called sohan. Afterward, I grab a balcony seat at a traditional Shirazi restaurant. Nibbling on kebabs and flatbread, I peer down at a group of musicians in the courtyard. They are playing rousing folk tunes to the delight of the diners, who sway and clap their hands. I get the impression that if dancing wasn’t banned, they’d all be up on their feet.

Back on the streets, I’m drawn again to the striking, but heavily made-up faces of the women. The natural look holds no truck among Iran’s urban sophisticates: when your face is the only attribute you can respectfully reveal to the world, you want it to look its best. Beauty salons—even the one I visit on a slow day—do a roaring trade.

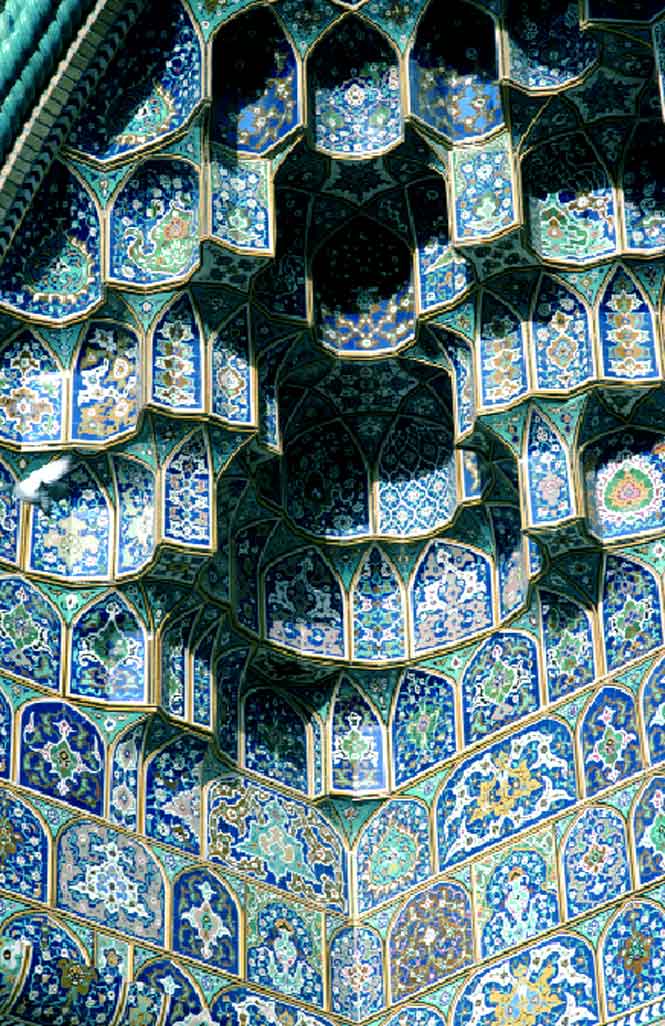

I don a chador myself the next day for a tour of the mausoleum of Shah-e Cheragh. Enshrined within is the tomb of Seyed Amir Ahmad, brother of Ali al-Rida, the eighth of the Twelve Imams (successors of the Prophet Muhammad). I linger among prostrate pilgrims, dazzled by the mosaic of silver tiles and mirrors on the walls and dome. My next stop is the Regent’s Mosque—Masjed-e Vakil. Here, amid stone columns carved with spiral designs, I struggle with my chador, a floral blue-and-white affair that has no fastenings. A Shirazi housewife comes to my rescue, showing me how to wrap it under my chin and hold it tight. I feel like a billowing ghost.

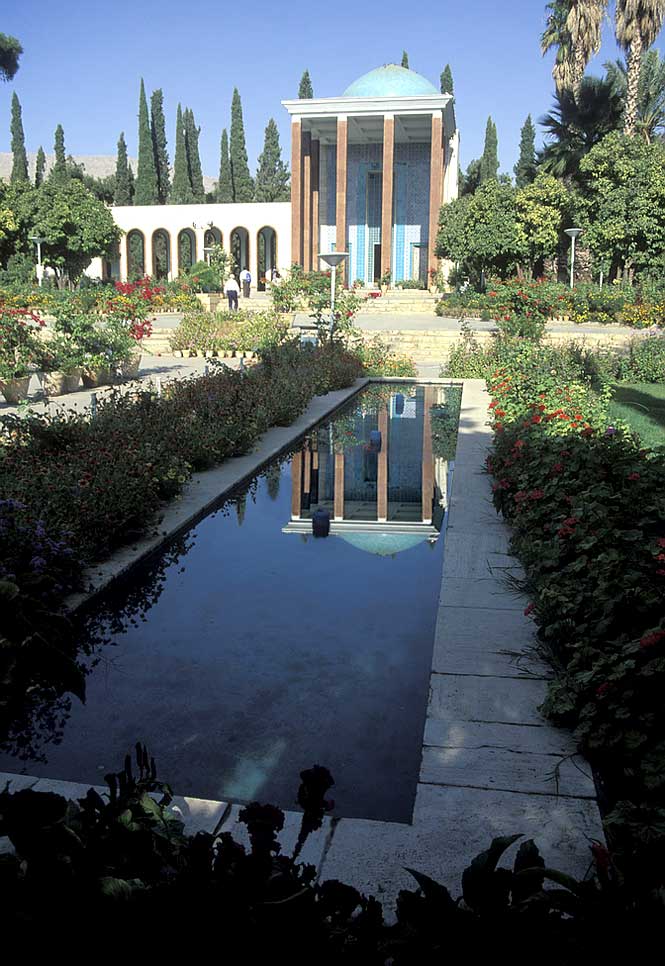

The mosque is virtually deserted, but it’s another story at the Musalla Gardens, final resting place of the great Sufi poet Hafez. At sunset, it seems like all of Shiraz has congregated here, milling about among the cypress trees and rose gardens. Iranians are a romantic bunch and they take their poetry seriously—the ghazal (an ancient lyrical form written in couplets) of Persian masters are still taught in school, and Hafez, who lived in Shiraz in the 14th century, is revered.

Mysticism features prominently in Hafez’s oeuvre, as do the more illicit pleasures of wine, women, and dancing. His poetry has even given rise to a popular method of fortune-telling: you open a page of his verse at random, read it, and divine your future in his words.

Naturally, I’m keen to have a go, and in the open-air pavilion that houses the tomb, I join the young women who sit clutching books of Hafez’s poetry. One sees me peering over her shoulder and sweetly hands me her volume. I shut my eyes and choose a page. My new friend recites the first stanza on it in Farsi, softly and with feeling. “What does it mean?” I ask. “It’s love, it’s good,” she replies.

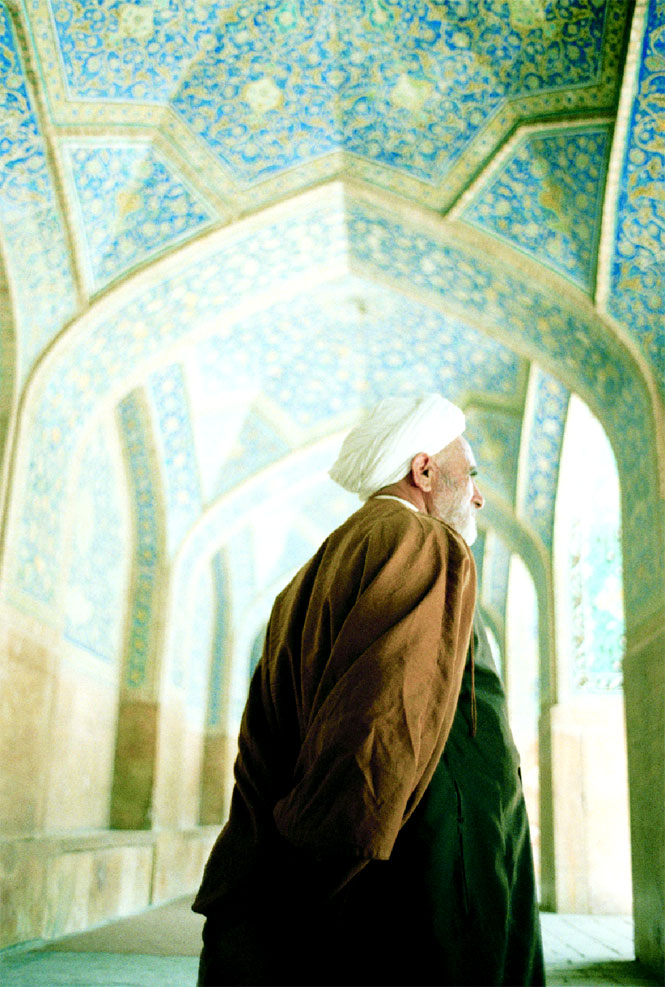

Shiraz hasn’t cornered the market on lyricism, though: that honor belongs to Esfahan (also spelled Isfahan), some 350 kilometers to the north at the foot of the Zagros Mountains. The city, beloved of Iranians and foreign visitors alike, brims with elegant mosques, lush gardens, arched bridges, and glittering palaces built by Shah Abbas I, a charismatic despot whose patronage of the arts kicked off Esfahan’s golden age in the 16th century. Its grandeur, then as now, is encapsulated by an old Farsi adage, Esfahan, nesf-e jahan—“Esfahan is half the world.”

I’m staying at the legendary Abbasi, a former caravanserai and now arguably Iran’s finest hotel. The big draw is its courtyard, which is designed as a classic Persian garden. When I sit down amid rosebushes and fruit trees one afternoon, a gardener plucks a tiny apricot and wordlessly hands it to me. The snack only whets my appetite, and that night I overindulge at the hotel’s buffet restaurant on specialties like fesenjan, a rich stew of chicken, walnuts, and pomegranates.

Early the next morning, mindful of the calories I’ve eaten, I visit the Abbasi’s health club. The facilities are strictly segregated; the women’s hours are from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. For all that, it still feels strange to be shedding clothes. As I step into the pool, I’m greeted by a local lady, elegant in a peacock-blue swimsuit. “Welcome to Esfahan,” she says warmly as we collide in the shallow end.

I want to linger in the steam room, but Imam Square, an easy 20-minute stroll from the hotel, beckons. Built in the 17th century, it’s said to be the largest public plaza in the world after Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. One end is dominated by the massive Imam Mosque complex, clad in the city’s trademark pale-blue tiles. But I prefer the more intimate scale of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, a few hundred meters away, with its mesmerizing mosaic dome.

Horses pulling carriages clip-clop over paving stones. Women sit chatting on grassy lawns. A group of schoolgirls gathers around me. “Where are you from? What do you think of our country? Do you like Esfahan? Welcome! Welcome!” they chatter effusively. One actually reaches out and hugs me. “We love you,” she says.

After an hour under a cloudless sky, I head for the shade of the bazaar at the square’s southern edge. With a high, vaulted ceiling, it’s an Aladdin’s cave of intricate Persian carpets, finely painted miniatures, decorative tiles, and other treasures. My bag is soon bursting with souvenirs. Deep within the maze of market stalls, I stumble upon Azadeghan, a chaykhuneh (teahouse) with an appealingly clandestine air. Following the lead of the men at the adjoining tables, I take a pull from a water pipe stuffed with apple-flavored tobacco, and splutter. Tea and saffron-infused rock candy—what the girls next to me are snacking on—goes down better.

Later, in a traditional gymnasium known as a zurkaneh—literally, “house of strength”—I witness a centuries- old sporting practice that is currently enjoying a revival. “Islam is good!” booms a bearded musician from his station, high on a platform, behind a drum kit. That’s the cue for a team of 10 men to enter an octagonal pit and perform a series of ritualized feats to a deafening drumbeat and songs. It’s a fusion of wrestling, aerobics, juggling, and dervish-style whirling that dates back to Parthian times. “The zurkaneh brings us closer to God,” offers the gentleman sitting next to me.

For me, closer still is a stroll along the Zayandeh River, the broad, park-lined waterway that makes this desert city so green—its name means “giver of life.” As soon as the heat of the day has abated, Esfahani families head for the riverbanks, picnic baskets in tow. I get lost on the way to the pretty Khaju Bridge, one of several old stone bridges spanning the Zayandeh. As I fumble with my map, a woman jumps up from her picnic spot and points me in the right direction. Under the Khaju’s narrow stone arches, I can see the silhouettes of discreetly entwined couples who are smoking, laughing, and whispering of love.

Back in the courtyard café at the Abbasi, my waiter asks me, “Do you like Esfahan? And Iran? Will you return?” I don’t need to consult the poetry of Hafez to reply. The answer, of course, is yes.

THE DETAILS:

Iran

Getting There

Emirates (emirates.com) flies daily to Tehran from Singapore and Hong Kong, with stopovers in Dubai.

Where To Stay

In Esfahan, be sure to check into the Abbasi (98-311/222-6010; abbasihotel.com; doubles from US$120), perhaps Iran’s most atmospheric hotel. Considerably more contemporary is the Pars International Hotel (98-71/233-6380; pars-international-hotel.com; doubles from US$107) in downtown Shiraz, where the mod cons more than compensate for the lack of character.

Tours

Independent travel in Iran has never been easier, but group tours are still a good strategy, if only for expediting your visa. The author traveled with UK-based Wild Frontiers (wildfrontiers.co.uk), which can also create tailor-made itineraries.

What To Do

No trip to Iran would be complete without a visit to Persepolis, 70 kilometers from Shiraz. Founded around 520 B.C. by Darius the Great, the ruins of the ancient capital rise up from the desert on an enormous rock platform, a magnificent maze of columns, bas-relief gateways, and broken palaces.

Originally appeared in the February/March 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Iranian Revelation”)