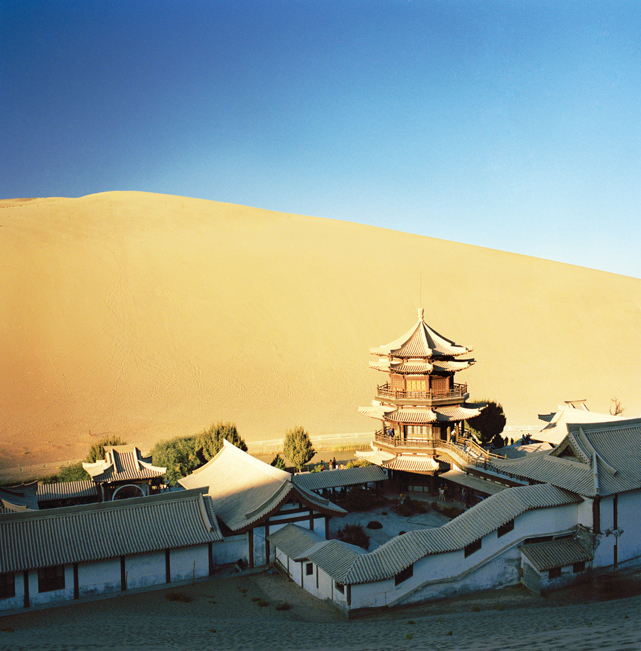

Founded two millennia ago as a garrison town on the edge of the Gobi Desert, Dunhuang is rich in Silk Road history, culturally diverse, and home to some of antiquity’s finest Buddhist art. Add a camel trek across sand dunes to the mix, and you’ve got one of the most beguiling destinations in western China

Photographs by Philip Lee Harvey

Though I’d lived in China for years, work and inclination had rarely taken me far beyond the populous, pulsing east coast. And not once had I considered venturing into the country’s desolate northern desert regions, the Gobi and the Taklimakan—the latter’s Turkic name, popularly translated as “you can go in, but you won’t come out,” wasn’t exactly the stuff of tourism slogans.

So when my friend Harvey Thomlinson, a Hong Kong–based translator and history-buff, suggested we team up for a visit to an ancient frontier city situated between both deserts, I needed some convincing. “Dunhuang is extraordinary!” he insisted. Harvey had visited Dunhuang a decade previously and was planning a valedictory tour before he returned to the United Kingdom. But I’d met my fair share of old China hands besotted with some obscure place they’d visited in the heady days of puerile Sinophilia. What could we possibly find in an arid corner of one of China’s poorest provinces, Gansu?

All I knew of Dunhuang were the Tang Dynasty poems I had read in university. They described it as the end of the world. “I water my horse and cross the autumn river, the water is frigid, the wind piercing. Beyond the flat desert a weak sun sags,” lamented the eighth-century scribe Wang Changling. “Let us finish another cup of wine, my dear sir, you’ll have no chance to meet a friend beyond the Yangguan Pass,” warned his contemporary Wang Wei.

Ultimately rationalizing that all travel, even the most arduous, has its rewards, I committed to enduring several hours of torment on a connecting flight through Xi’an. It was during the closing minutes of our final approach to Dunhuang, when I caught my first glimpse of a green atoll lost in a spellbindingly grand sea of yellow, that I felt my reservations dissipating like the plane’s vapor trail.

In the days that followed, it wasn’t just the beauty of the desert that enchanted me. It was discovering the role that Dunhuang, founded in antiquity as a small garrison town at the gateway to the Silk Road, had played in shaping China itself—and in the remnants of this illustrious past still visible in cave murals or softly fading from view along the sand-soaked imperial frontier.

It was a long drive through flat, barren terrain before we came upon a series of earthen mounds. Ninety kilometers northwest of Dunhuang, the 20 sand-scoured watchtowers that protrude from the wilderness are all that’s left of this section of the Great Wall, built by Han emperors two millennia ago.

“You can see why it inspired such poetry,” Harvey said, looking out across a dusty plateau to the rugged mountains beyond. “For the Chinese, civilization literally ended here.” Indeed, it was easy to picture the Xiongnu—the first of many “barbarian” people to menace China—rushing into view across this savage landscape.

A rammed-earth fort still stands at the Jade Gate, an ancient pass that once guarded the eastern end of the Hexi Corridor. Known as the Small Fangpan Castle, the roofless, thick-walled building is testament to the reach and sophistication of China’s early bureaucracy. “During the Han dynasty, traders, envoys, and soldiers entering or leaving the kingdom would have their documentation processed here, just like in a modern customs offices,” a chirpy guide explained.

One notable individual to depart China by way of Dunhuang was Zhang Qian. At Yangguan (Sun Gate) Pass—another Han border crossing a few kilometers’ drive to the southwest—a museum tells the story of Zhang’s exploits. In the second century B.C., the expansion-minded emperor Wudi dispatched Zhang into the Western Regions (as the Chinese once called the lands beyond their realm) to try and establish trade links with kingdoms beyond the nomad-plagued wilderness. Zhang returned with the first reliable information the Chinese ever had about Central Asia, in essence opening up China to global trade. To give you a sense of what it would have been like to exit China via these ancient passes, a re-created fortress next to the Sun Gate’s crumbling remains issues bamboo scroll passports to visitors, each inscribed with their name, or its Chinese equivalent. Sure, it’s touristy, but it does make for a nifty souvenir.