Even as tourism reshapes Luang Prabang into a more worldly destination, the inimitable appeal of the former Lao capital—and the lush countryside surrounding it—endures.

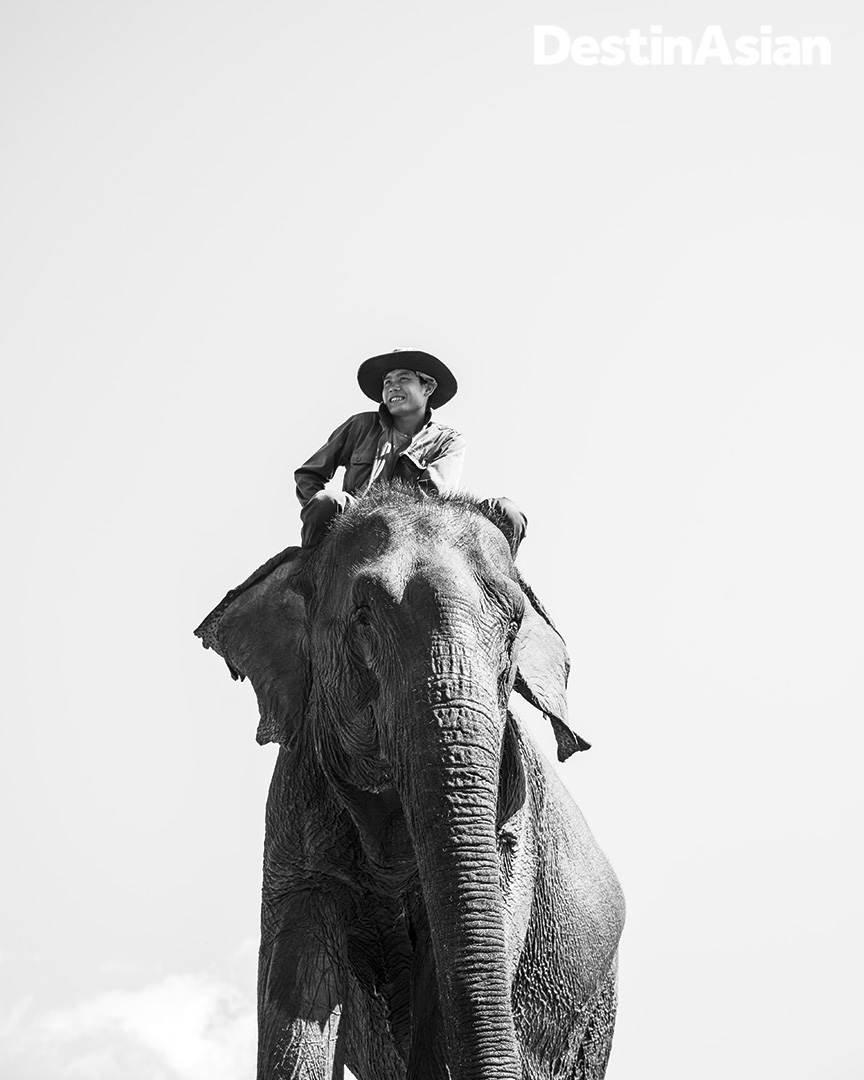

On a humid mid-October morning beside the Khan River in northern Laos, I pondered the odd sensation of elephant ears flapping against my shins. They were coarse and leathery, yet in parts felt as soft as silk. Short, wiry hairs periodically pricked my legs as the ears fanned back and forth. It was unlike anything I’d ever experienced, yet for all its unfamiliarity, it helped me feel more connected to my mount, a patient, four-ton pachyderm named Mae Thongkham, or “Mother of Gold.”

Luang Prabang’s Royal Palace Museum, originally built in 1904 as a residence for the country’s bygone monarchs. Photo by Lauryn Ishak.

I was at Elephant Village, 18 kilometers east of Luang Prabang, riding bareback—or, more precisely, bareneck—along the sludgy riverbank. In business since 2001, Elephant Village is one of a handful of elephant-riding operations in the area. But it is the only one, as of last September, that has done away with howdahs, the wooden seats typically used to transport tourists. Harnessed to the elephants’ backs, these heavy contraptions are decried by animal rights groups as the cause of spinal damage, abscesses, and other injuries. “Some travel agents won’t sell our excursions any more because we don’t use howdahs,” Harry Bloom, the outfit’s rangy English marketing manager, told me. “But it’s the right thing to do. We want the people who ride our elephants to care about their welfare too.” Say what you will about the ethics of riding elephants at all, but the animals at Elephant Village, rescued from the logging industry in neighboring Xayaboury province, seemed quite carefree as they carried us one kilometer to the river for their daily bath before heading home into the forest with their mahouts.

In a way, Elephant Village’s stance on the howdah echoes a broader sense of change percolating in Luang Prabang—that of a city maturing from languid ingénue to major, worldly Southeast Asian destination. Afforded UNESCO World Heritage status in 1995 for its well-preserved fusion of traditional Lao structures and European colonial architecture, Luang Prabang, which sits on a lush peninsula at the confluence of the Mekong and Khan rivers, is poised to take off. The aeronautical metaphor is apt: last year, a number of new airlines debuted direct flights here from their Southeast Asian hubs: Thai AirAsia from Bangkok, AirAsia from Kuala Lumpur, and SilkAir from Singapore. Hong Kong–based HK Express plans to launch a service soon, as does Thai Airways’ regional subsidiary Thai Smile.

The town is also witnessing something of a hotel-building boom. At the tip of the peninsula, where the brown waters of the Khan curl into the Mekong, I saw workmen sanding meter-long slabs of timber for a new property. Near the Hmong Day Market on the corner of Sisavangvong and Kitsalat roads, the Azerai, a brand-new hotel project by Aman founder Adrian Zecha, was being readied for its January opening. Rosewood will unveil a luxury tented camp about 15 kilometers outside town later this year, while French hotel group Accor has just cut the ribbon on an 80-room Pullman resort on the road to Kuang Si Falls, one of the area’s most visited attractions.

Accor has also recently refreshed and rebranded its two existing hotels in Luang Prabang. Right in the center of the heritage zone, 3 Nagas has just 15 rooms spread across two of its trio of historical buildings, one of which once served as the ice creamery for the Royal Palace (now a national museum). Post upgrade—new furniture, renovated bathrooms, better lighting, more vibrantly painted interiors—it’s now part of Accor’s MGallery by Sofitel collection. On the other side of town, all-suite sister property Hôtel de la Paix, the onetime residence of the French governor, received a more intense transformation to become the Sofitel Luang Prabang. The previously underwhelming entrance was moved, invigorated by giant bronze elephant sculptures and artfully lit steps that produce a dramatic sense of arrival. “Here you experience Lao culture first,” Alexandre Garcia, the young French general manager told me, as he pointed out three 50-year-old wooden houses transported from the countryside to serve as the hotel’s reception area, spa and fitness center, and a cooking school.

The bulk of the property comprises four buildings that wrap around a large courtyard. Their invigorated suites now feature mosquito-netted four-poster beds, a fresh new palette, and back gardens with gazebos and outdoor tubs. The courtyard, once covered in brick and concrete, is now a botanic garden, with a serene pond and hammocks dotted around the grounds. And the pool area has been upgraded with cabanas and a fire pit. Sitting outside at night, with lanterns glowing along the pathways, guests will sense time slackening, a wholesale slowing down that mirrors the quiet appeal of the town.

Tourists have been flowing into Laos’s former royal capital ever since it acquired World Heritage status. They wander streets populated with well-preserved Asian and European architecture and soak up the almost passive, village-like environment: one happy by-product of the UNESCO accreditation is that swimming pools cannot be built on the peninsula, keeping large hotels at bay. Yet the town’s fame belies its size, and it’s hard to put a finger on just what makes Luang Prabang so beguiling. It is small (about 60,000 residents), has some pretty Buddhist temples, some fine places to eat, and a few mildly interesting caves along the Mekong. But there’s no must-see-before-you-die attraction, no gargantuan temple complexes, no world-renowned day or night market, no celebrity-name chefs, no driving nightlife or bar scene. It’s a river town that goes to bed early and whose highlight for many is rising at dawn to watch monks shuffle barefoot through town collecting alms. But inexplicably seductive it is. Travelers just seem to inhabit Luang Prabang’s fabric as they wander side roads that rise and fall from the peninsula’s spine, browse through the displays at a jewelry shop, or snap photos of painted wooden shutters and gilded stupas, basking in the unfussy languor of it all.

Times, though, are changing. The town where people come to do nothing in particular is becoming a busier, swankier, more-rounded destination. I had last been in Luang Prabang in late 2015, staying at a basic guesthouse on the far side of the Khan River. Every morning, I’d cycle down Mahaouparath Phetsarath Road to an unnamed little shack of a restaurant for my daily green-papaya salad, sticky rice, and pineapple shake. The street felt semi-rural then, its low-rise buildings separated by patches of greenery. When I returned a year later, I noticed numerous plots for sale and plenty of new development: the single-story house opposite that little shack restaurant was being recast as a multi-story building.

Tourism these days is the lifeblood of Luang Prabang, so it would be churlish to quibble about change, especially when it comes in the form of Saffron Coffee’s revamped location on riverfront Khem Kong Road. Now called Saffron Espresso, Brew Bar, and Roastery, it’s a casually cool spot with terra-cotta floor tiles, a wall covered in hessian bags, and an impressive-looking roasting machine front and center. And the coffee—I tried an iced latte—is exceptional, made from organic, shade-grown arabica beans cultivated by hundreds of hill-tribe families in northern Laos.

A new drinking establishment has similarly raised the bar. Englishman Andrew Sykes had worked in the investment industry for 20 years but had always fantasized about opening a watering hole in Britain. After visiting Luang Prabang on holiday in 2013, he kept the dream but revised the location, spending two years renovating a 1970s cubist house near Wat Manorom before opening 525 last July. It’s a swish, sophisticated cocktail bar that wouldn’t look out of place in any global city, with caramel banquettes, exposed-filament bulbs, and black-and-white photos of Southeast Asia accompanying a generously stocked bar, and a well-conceived menu of comfort food. “I wanted to have a place that is an ode to anyone that works and wants a drink at the end of the day,” Sykes told me late one night. “In London my colleagues would always tell me when it was five to five [i.e. 4.55 p.m.], time for a drink. That’s how the name came about.”

As for Jason Deshay, an American who once captained yachts in the Caribbean, when he first came to Luang Prabang three years ago he immediately noticed an absence of luxury on the water. So he built the 12-passenger Dok Keow (“Green Flower”), a lean, 28-meter-long riverboat that debuted at the end of 2015. Made of teak and rosewood, and with a full kitchen, high balustrades along the side with carved leaf motifs, and two cabins with en-suite bathrooms, it is by some distance the most polished vessel on this stretch of the Mekong. During a remarkably affordable (US$35 per person) two-hour sunset cruise—including wine, cheese, and local snacks—the boat cruised downstream, turned back toward Luang Prabang, and as it pushed against the current, the Dok Keow felt as though it were hovering on the river. When the misty mountains and the lights of the peninsula, peeking out between palm trees, came into the frame, it felt like I’d stumbled on some remote outpost.

Perhaps the most surprising business to emerge here of late is the country’s first buffalo dairy farm. Run by two couples—one Australian, the other American—who moved here from Singapore, Laos Buffalo Dairy is set on 20 hectares of land near Kuang Si Falls. “I had a big job that was getting to be too much, and we decided to take a break so our daughter could really experience Asia,” Susie Martin, one of the owners, told me at the guesthouse she runs in town. “After tasting buffalo curd in Sri Lanka, we thought, maybe a dairy would work in Luang Prabang, where there’s a shortage of fresh cheese and yogurt. We talked to hotels and shops and they all wanted in.”

I went out to see the operation and got my first whiff of Laos’s heart-stirring countryside. Steven McWhirter, Martin’s husband, showed me around the buffalo sheds and silos under construction. At the time the farm had nine buffalo, though they expected that number to grow to 100, all rented from local farmers. “Tourists will be able to see what we are doing, visit the research center, feed a buffalo calf with a bottle,” he said. They also plan to develop a biogas project and eventually open a kitchen and farm-to-table café. The location is alluring and tranquil, with open fields and rice paddies stretching to the mountains behind the farm, and the products are sublime: the yogurt is denser and more flavorful than the traditional store-sold goop, while the milk is smooth, creamy, and sweeter than cow’s milk. I was sold.

Not far away, Living Land, another enterprise that showcases Luang Prabang’s natural bounty, was a community farming area until 2006. In 2011, it started tours under the guidance of Laut Lee—the farmer who manages the venture—to help tourists better connect with an intrinsic component of Lao life and culture. The half-day program, designed for a maximum of 20 participants, traces the cultivation of rice from planting, cutting, harvesting, and threshing to preparing and cooking, as well as demonstrating traditional village methods of bamboo weaving, squeezing sugar cane, and blacksmithing. “Many people think rice just comes in a box. We believe rice is life,” Lee explained. Though rice is the focus, Living Land also grows organic vegetables and herbs to sell to hotels and restaurants in town, the proceeds from which are used to support the education of local farmers’ children.

Keen to see more of Luang Prabang’s verdant surrounds, the next day I joined a trek with local adventure operator Tiger Trail. Soon after we started walking under an overcast sky, my Hmong guide, Ai Lao, began identifying various medicinal plants along the trail, including the elephant leaf plant, whose taro-like root can be boiled into a tonic for treating malaria, and other leaves that stop bleeding or relieve a headache. Our first stop was Houy Nok, a community of Khmu—just one of dozens of hill tribes living in the mountains of northern Laos—where 64 families live amid a veritable orchard of tamarind, sweetsop, mango, pomelo, and pink apple trees. Ducks and geese waddled around the bamboo-and-cement homes. We exchanged pleasantries with some of the village women before setting off again, just in time to be soaked by a torrential downpour. Ai Lao merely shrugged, as if to say, “What did you expect?” Undaunted, we pushed on through the forest along muddy tracks.

The rain stopped when we reached a Hmong village called Long Goud, set at the base of a mountain beside a still body of murky water. Home to five families living in tin-and-bamboo shacks, it was completely cut off from everything, a reality that I found both inspiring and terrifying. We walked around and Ai Lao showed me lemongrass, sweet potato, eggplant, and chili plants, as well as a raised bamboo hut full of dried corn. At the last house we passed, a couple in their early 60s were seated on the front deck. Ai Lao greeted them in Hmong and they ushered us inside. Though it was lunchtime, the interior was dim enough to suggest it was dusk, and items hung from strings wherever I turned—pots, plastic containers, clothes. Fish dried on a small rack above some embers, while a basket by the couple’s bed contained a giant pumpkin—feed for their pigs. Ten people used to live here, they explained, but most had grown up and moved away, to seek work in Luang Prabang or beyond.

Eventually we left the forest, and as we shuffled along a terraced hillside, the view opened to mahogany- and teak-blanketed slopes and verdant karst outcroppings. It was a tiring, rewarding, thought-provoking day, with stunning scenery throughout. But what I found most unexpected was the complete absence of a single other tourist. How much longer, I wondered with a mixture of excitement and angst, would that be the case?