An off-road adventure through the wilds of this vast, empty country provides an exhilarating connection to the land and its people, as well as the chance to help bring back an ancient strain of herding dog that has all but disappeared from the steppe.

Behind the wheel of the cushy, top-end Toyota Land Cruiser our convoy had christened “James Bond,” Kentucky gun shop owner Barry Laws put his foot to the floor and lit out across the South Gobi. A herd of black-tailed gazelles, drawn instinctively to the race, bounded up beside us, flattening closer to the ground with every gallop. Watching the speedometer and calling out the reading to me and our trusty navigator, a New York ad exec named Jo-Marie Fecci, Barry pushed the streaking antelopes to 65 kilometers per hour before easing off the pedal and allowing the herd to flash past.

From the back seat, I watched the animals sprint across the sand, pelting headlong for the sheer joy of it. The billowing khaki cloud kicked up by James Bond’s wheels was fading into the desert behind us. The rest of our caravan—four other Land Cruisers of varying vintages, a Ford Ranger pickup, and a Russian-made four-wheel-drive camper van called a Furgon—had dropped out of sight. Losing them was a violation of the cardinal rule of the off-road convoy. But I couldn’t help but share a little of the gazelles’ exhilaration. Around us, the Gobi stretched out to the horizon in all directions: a vast, glorious, wild emptiness.

Along with a half-dozen off-road enthusiasts, I had embarked on this two-week, 2,700-kilometer drive across Mongolia a few days before, rolling out of Ulaanbaatar toward the wind-sculpted cliffs of Tsagaan Suvarga. Leading the way was Bruce Elfström, an American entrepreneur who had conceived the expedition as a way to raise awareness and generate funds for his Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project, a nonprofit scheme dedicated to breeding back one of the world’s oldest herding dogs. Distantly related to the Tibetan mastiff, the mammoth black-and-tan bankhar was for thousands of years integral to the nomadic culture of the steppes, protecting livestock from the predations of wolves and snow leopards. But when Mongolia’s communist government began collectivizing the nomads’ herds in the 1920s, the bankhar fell out of favor. Large, fierce, and territorial dogs were anathema to cooperative herding, and amid the growing Soviet influence over the country’s affairs, the bankhar was an undesirable symbol of Mongolian nationalism. By the time Elfström came to know about their existence, they had practically disappeared.

The 50-year-old son of documentary cinematographer Robert Elfström, Bruce first visited Mongolia in 2004 while location scouting and handling ground logistics for an IMAX movie called Dinosaurs Alive! He and his team were staying with a community of nomads when one night the darkness erupted with the screaming of horses and bleating of sheep, punctuated by the yips and snarls of a roving wolf pack. When he went out to survey the carnage the next morning, his hosts told him they had lost 17 horses and some 30 sheep and goats—a substantial part of their livelihood.

Bruce, who had trained in biology at New Mexico State University, had seen livestock guardian dogs at work on American ranches, and he wondered why Mongolia’s pastoral nomads didn’t use their own. When he learned that an indigenous breed had, in fact, once been common to the steppes, he resolved to do something to help.

With Bruce busy raising his two daughters and growing his Connecticut-based off-road driving business, Overland Experts, it would take the better part of a decade for the Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project to come to fruition. But three years ago he bit the bullet and sent one of his employees to Mongolia—cold—to suss out what would be required to breed back the country’s native herding dog.

“I think the tipping point was really my inner struggle with the idea that I wasn’t giving anything back to the world,” Bruce told me. Since then, he has sunk about US$80,000 of his own money into the bankhar project, primarily to acquire land for a breeding and training facility and to pay the salaries of the three Americans and three Mongolians who have worked on various aspects of the venture’s implementation. Along with a web-based fundraising campaign and an ongoing search for sponsors, the trip I’d joined was an attempt to make the operation more sustainable: priced at about US$4,000 per person, excluding airfare, its proceeds go directly to the dog project. The idea is to give off-road driving fans and dog lovers a window into Mongolian culture, as well as a brief introduction to the ecological issues that underlie the importance of Elfström’s efforts.

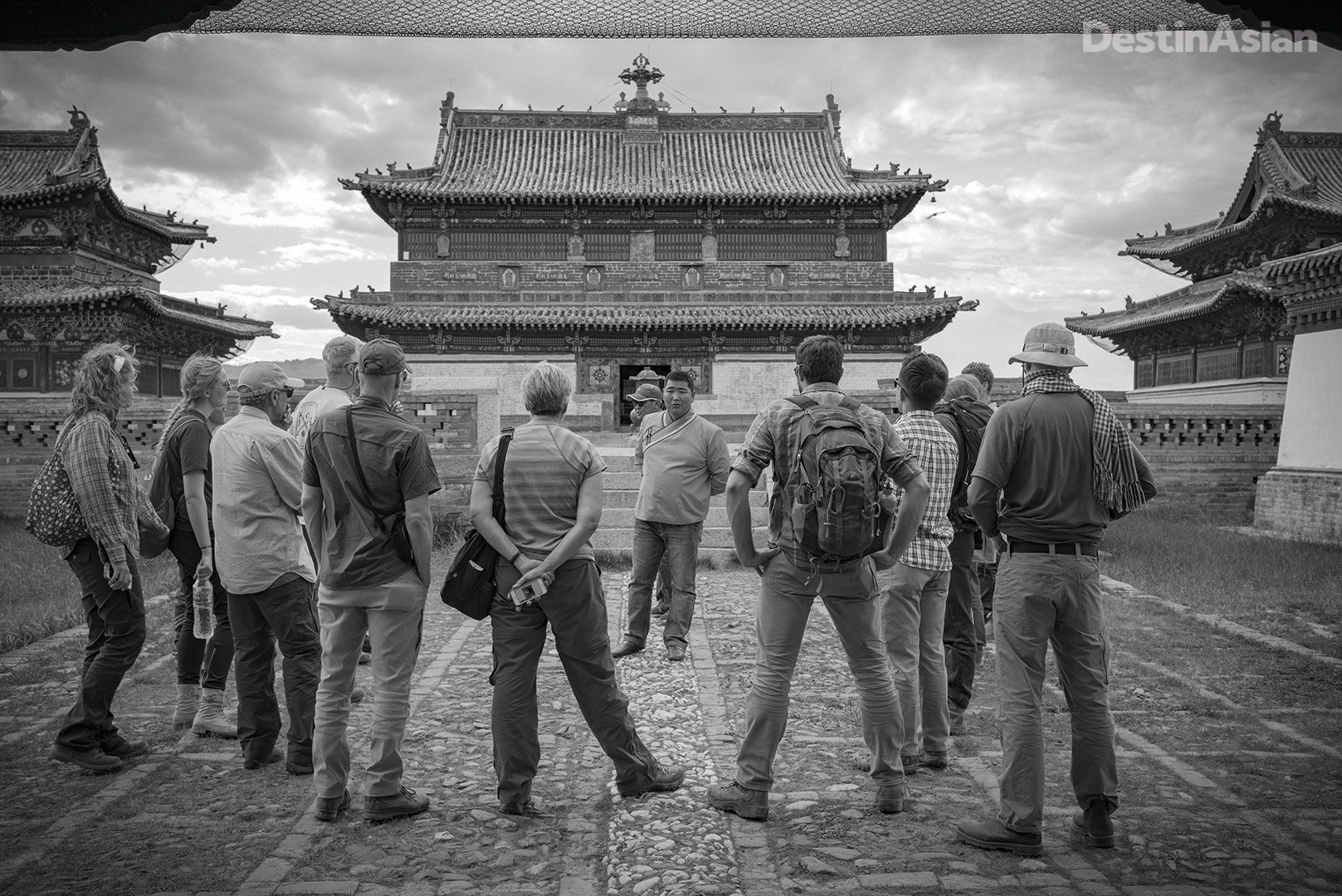

A tour of the ancient Erdene Zuu Monastery near Kharkhorin, some 370 kilometers southwest of Ulaanbaatar. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dunn.

For me, it was hard to imagine an adventure better designed to capture my interest. After adopting a Labrador retriever from a local shelter in New Delhi, where I live, I had developed something of an obsession with all things canine. I’d also been meaning to visit Mongolia for more than a decade, ever since I first encountered the great travelogues of Owen Lattimore, the monocle-sporting American Orientalist known to the Mongols in the 1930s as “Solitary Glass.” I’d also recently burned through all five volumes of Conn Iggulden’s Conqueror series of historical novels about Genghis Khan, whom Mongolians believe was sired by a blue wolf, making dogs and humans “of the same bones.” Mongolia and the bankhar did not disappoint.

A third the size of all the countries of Southeast Asia combined, Mongolia is home to a mere three million people, nearly half of whom live in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. Though economic growth soared as high as 25 percent during the commodities boom of the past decade—thanks to gold and copper mining—the vast majority of the country is beyond undeveloped. It is empty. Empty of cities. Empty of towns. Empty of villages. Empty of factories. Empty of farms. Empty, even, of trees. And with no railway and only 5,000 or so kilometers of paved roads, all travel in Mongolia—or at least all travel worth bothering about—is essentially off-road travel.

Elfström and his daughter Petra with a pup from the Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dunn.

Sojourners navigate by GPS or the sun or the seat of their pants, as if sailing on the ocean, and the “roads” are typically nothing more than the tracks of other vehicles, sometimes spreading to eight or ten “lanes” due to convoy drivers fanning out to avoid the dust kicked up by the jeep or truck ahead of them. Beyond some basic training, Bruce’s bankhar expeditions don’t require much technical skill from their drivers. In off-road parlance, this is “overlanding,” as opposed to “wheeling,” meaning the focus is on navigating around obstacles rather than deliberately seeking them out. As such, we drove through sand and dry riverbeds, and we changed our fair share of tires and fuses, but we never broke out the winch or hi-lift jack.

Mongolia’s oceanic emptiness was itself wonderful to behold. But that doesn’t mean there was nothing to see. Over the past three days, we’d explored the ruins of the 17th-century Ongi monastery, which was all but leveled during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s; visited the stunning rock formations of Tsagaan Suvarga; and hunted for fossils among the famous “Flaming Cliffs” at Bayanzag, where American adventurer and naturalist Roy Chapman Andrews made the world’s first discovery of dinosaur eggs in the 1920s. And that very morning I’d hiked out to a rock cropping a few hundred meters from our encampment to examine a series of millennia-old petroglyphs—simple yet beautiful drawings of hunters, horses, and big-horned argali sheep. And now, we were racing across the desert in search of the summer home of a family of herders who’d received a puppy from the project’s first litter a year earlier.

Luxuries, needless to say, were few and far between. Most nights we slept in traditional felt-and-canvas tents at simple “ger camps” set up for tourists, where the cots were invariably hard and the best thing you could say about the food was that it was edible; the troll’s line from The Hobbit—“Mutton yesterday, mutton today, and blimey, if it don’t look like mutton again tomorrer”—kept running through my mind. Other times we pitched our tents under the stars. The one brush with luxury came on day three, when we bunked down near the town of Dalanzadgad at Three Camel Lodge. Guests sleep in gers here too, but ones appointed with comfy hand-painted beds and en-suite bathrooms with hot and cold running water. And the toothsome chicken cordon bleu I had for dinner made a welcome break from Mongolia’s sheep-centric cuisine.

But creature comforts were beside the point. For me, the real attractions of Mongolia were the land and its people. Along with countless gazelles and wild Bactrian camels, every so often we’d happen across a lone herdsman or family of nomads driving a herd of sheep and goats or the half-feral horses that Genghis Khan used to conquer most of the known world in the 13th century. There was a timeless character to these encounters. And as we skittered across the desert it was easy to imagine that little had changed since Chapman Andrews pioneered off-road driving—and gazelle-racing—here in a 5.2-liter Dodge Brothers touring car in 1922.

That was an illusion, of course. Today’s nomads are as familiar with mobile phones and satellite TV as they are with camels and goats—and the ongoing sprint into modernity has brought with it a host of problems. Since Mongolia abandoned its communist system in the 1990s, nomadic families have altered their lifestyles dramatically. With no regulator to limit the size and composition of their herds, and with the rangeland still open to anyone to graze his animals, herders have steadily acquired more and more livestock. At the same time, a cashmere boom prompted by surging demand in China drove many to abandon the traditional “five snouts”—horses, sheep, goats, cows/yaks, and camels—in favor of raising goats alone. The dismantling of the communist purchasing system and cooperative pasture management, meanwhile, has made the nomads more sedentary, simply so they have a market for their meat and wool.

Camping under the stars deep into the wilderness of Mongolia’s southernmost province, Ömnögovi. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dunn.

The results have been disastrous. Largely because of overgrazing, Mongolia’s fragile pasturelands are rapidly turning to desert. Throughout our trip we came across clumped tufts of needle and bridle grass that were as humped as moguls on a ski slope, as the wind had blown any sand not secured by vegetation to China—part of the Gobi’s 3,600-square-kilometer annual expansion. Outside Ulaanbaatar, billboards promoted Chinese and Korean tree-planting projects intended to block the traveling dust. And in one desolate spot, a lonely monument commemorated a 2010 meeting of Mongolian cabinet ministers to discuss the issue of desertification on rocky sand that was once covered in grass. A onetime literature scholar could not help but think of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias: “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Bruce believes his bankhar dogs can help. He tells me predators in high-stress areas like South Gobi province can kill as much as five percent of a nomad’s livestock every year, and that “buffer stock” is kept to account for those losses. Having bankhars on hand to guard the animals means herd sizes can shrink, thereby reducing overgrazing as well as the “retaliatory killing” of wolves and the endangered snow leopard by herders.

A few hours after James Bond had raced with the gazelles, I was growing impatient to see first-hand how the program was working. Around three o’clock that afternoon, we’d ruled out pitching our tents on a sunbaked sand anvil that was strewn with fist-size rocks. (“I could see stopping here if it was a really great campsite, but it’s not,” Jo-Marie had said). So now we were pushing into the endless twilight of the Mongolian summer, which lasts until 10 p.m. or later.

At the head of the convoy in the white Ford Ranger pickup, the two young American roustabouts who had set up the breeding program and placed the first set of pups with herders in the winter of 2014—20-year-old Devin Byrne and 30-year-old Doug Lally—appeared to have no idea where we were headed. Every so often, they’d pull onto a high spot and stop to reconnoiter, only to reverse course and head in another direction.

In the navigator’s seat, Jo-Marie was losing her mind. A former war photographer and an experienced overlander who’d competed in the Rallye Aïcha des Gazelles—a women-only rally across the Moroccan Sahara where competitors use old-school map and compass to plot the fastest route—she was equipped with a Garmin inReach GPS and a high-resolution topo map she’d downloaded from the Internet. But nobody had asked for her input, and most of the convoy’s walkie-talkies, including the one in James Bond, had lost their charge. “I know exactly where we are,” Jo-Marie kept saying. “But nobody has showed me on the map where we’re going.”

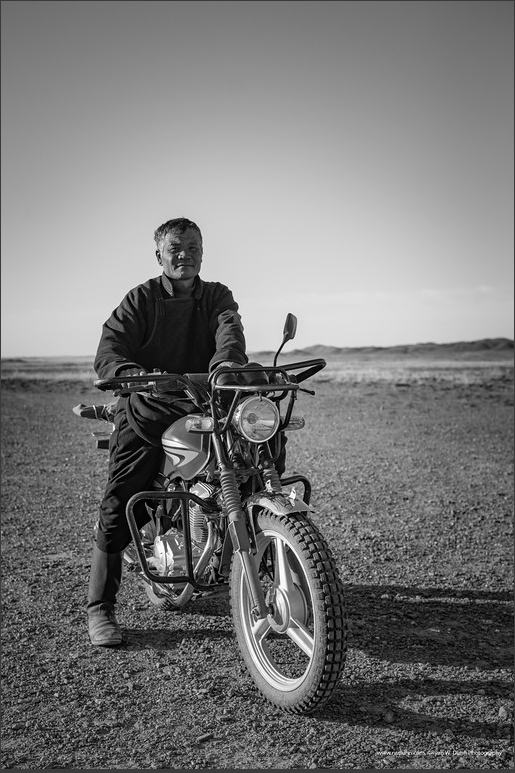

A local guide hired to navigate the convoy through the Gobi-Altai Mountains. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dunn.

Later, Lally, a happy-go-lucky former wildland firefighter with Groucho Marx eyebrows and the wide, triangular grin of a Guy Fawkes mask, explained the confusion. After a few months in Mongolia, where the nomads seemed never to be in the same place twice, he and Byrne had given up on GPS waypoints and the like and gone native. We were navigating Mongolian-style, which differs from being lost chiefly in the respect that nobody gets too bothered about it.

Finally, as dusk was falling, we crested a rise and looked down on a grassy valley. In one direction, a stream cut through a canyon that could have featured in one of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns. In another, rolling green hills followed the water to the horizon. We had arrived in Saran Khundi, or “Moon Valley,” which meant that Doug and Devin finally knew exactly—okay, almost exactly—where we were. Half an hour later, we rolled into the summer camp of one of the first herders to receive a pup from the bankhar project.

A large white ger stood in the shadow of the black foothills of the Gobi-Altai Mountains. Beyond it was another, smaller ger and a split-rail corral. Unlike the green hills of Moon Valley, the land here was rocky and sepia-toned. A thousand-odd head of cashmere goats dotted the rise.

At the slam of the pickup truck’s door, a shaggy black-and-tan dog streaked out of the pasture. Everything I’d read suggested it would be ferocious and territorial; Chapman Andrews, for instance, recounts several narrow escapes from corpse-eating dogs—“savage almost beyond belief”—in Across Mongolian Plains. And Bruce had advised everyone to get rabies shots before making the journey.

But the big, goofy bankhar that wriggled up to Doug and Devin and flopped on her back to have her belly rubbed was about as vicious as Winnie the Pooh, at least where people were concerned. No sooner had the nomad who owned her appeared than all of us were petting her and scratching her ears.

“Your bankhar remembers you,” the herdsman said in Mongolian.

Dressed in a blue tracksuit jacket and an argyle sweater, 64-year-old Otgonbayar had the weathered look of a man who spends his life in the sun and wind, with prominent, bronze cheekbones and deep wrinkles around his eyes. The first of several herders we’d meet during the “project-oriented” days of our journey, he was obviously proud of his bankhar, which he said had already reduced his livestock losses even before reaching maturity.

After a few minutes, Otgonbayar and his wife ushered all 17 of us—travelers and crew—into their ger. Soon, another honored guest arrived. This was a retired veterinarian named Adilbish, who’d taken Doug and Devin under her wing when they were first trying to make connections with local herders. Despite the bankhar’s cultural resonance, Adilbish’s support was crucial to convincing proud nomads to take advice on how to rear a dog to guard sheep from a couple of twentysomething Americans.

I was keen to learn how the family’s bankhar was working. But the visit also offered a rare glimpse into the life of modern-day nomads, that much more authentic because we were there with a purpose other than simple tourism. As Otgonbayar’s wife passed around a dented aluminum bowl filled with fried dough and Russian candies, I looked around the ger at the family’s meager belongings.

Unlike in the old days, Otgonbayar explained, he no longer moves with the seasons. The pasture here is good enough to graze his stock almost year-round. They get electricity from China, only 150 kilometers away, and the semi-permanent location means they can use a larger ger—perhaps six meters in diameter—and keep more possessions. But wolves and snow leopards are a constant worry.

“Just a few days back, I lost four sheep,” Otgonbayar told us. “The wolves were after them for three days running.”

His young bankhar had already started to make a difference, though. After dark, he relied on it to protect the sheep and goats in the corral. “Now we can sleep at night,” his wife piped in. And out in the mountains, too, Otgonbayar reckoned the dog had discouraged many attacks.

Over the next 10 days, as our convoy made its way through the Gobi, across the Altais, and deeper into the steppe, I would hear similar stories from other herders who had received dogs from the project’s first litter. But for me, it was a fuzzy mongrel that best captured the essence of the journey.

The encounter happened not long after we had stopped to air-down the vehicles’ tires for a drive through the powdery sands—and a quick tutorial from Bruce on driving over washboard—en route to the towering dunes at Khongoryn Els. We pulled up at a communal well that offered a panoramic view of the rolling desert and everybody piled out of their vehicles to take pictures and explore the well, which for some reason was filled with felt.

“Dog!” somebody cried out in warning, and we all scrambled helter-skelter back into the trucks, Chapman Andrews’ ferocious hounds and Bruce’s rabies shots still looming in our imaginations.

Moments later, a fuzzy black-and-tan puppy the size of a beagle flounced comically up to the well, and everybody piled out again to scratch his ears. He was covered in camel ticks, which Bruce proceeded to yank out with his Leatherman, and it was hard to tell whether there was a German shepherd or two among his ancestors.

But at a glance, the little guy was the spitting image of the bankhar pup, Barbuss, who’d traveled with the convoy to join the staff at Three Camel Lodge as the brand ambassador for the bankhar project. When Bruce finally turned him loose and he trotted across the dunes on his snowshoe paws, I could almost picture Genghis Khan beside him.