Any glimpses of modernity are quietly and inexorably swallowed by the sheer presence of the Altiplano itself—its scale, its dreamlike quality. We drive on, through a hallucinatory landscape bisected by waterways and monochromatic sandbanks, bright yellow against the muted plains. Distant mountains seem to float in the air, suspended on shimmering waves of heat. We traverse expanses of coarse ichu grass dotted with llamas and their dainty relatives, vicuñas, whose wool is among the most prized natural fibers in the world. And we spend our nights in simple guesthouses in Aymara villages, finding time one morning to help a group of farmers harvest protein-rich quinoa.

Bolivia’s southernmost province, Sur Lípez, unfolds as a primordial landscape of volcanoes and chemical lakes. The earth is infused with raw minerals—zinc, copper, silver—that paint a vivid surrealist canvas of perplexing scale. The high point of the trip, literally, comes at the Sol de Mañana geysers, 4,900 meters above sea level, which belch towers of sulfurous steam into the sky.

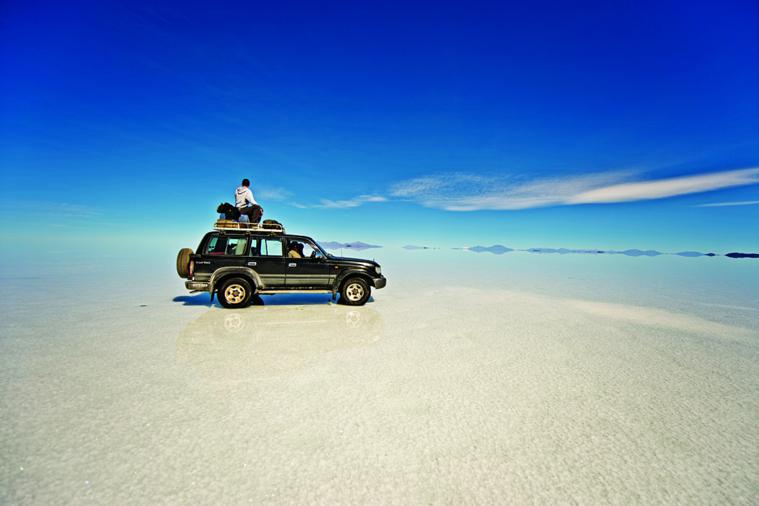

The Salar de Uyuni appears suddenly. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say it doesn’t appear at all: the rainy season has just come to an end and the edge of the immense salt flat is covered in a sheet of water that mirrors the cloudless blue sky. It’s like driving into nothingness. Yet locked in the brine below this 10,000-square-kilometer expanse is the world’s greatest reserves of lithium, a resource that promises enormous economic potential for South America’s poorest nation. Whether Bolivia will be able to profit from it remains uncertain: the socialist government of president Evo Morales, who nationalized the country’s oil and gas industries shortly after taking office in 2006, is intent on mining and processing lithium domestically, and commercial production has yet to begin.

For now, the Salar’s economic value is mainly as a tourist attraction. A number of “salt” hotels have sprung up to accommodate visitors. I spend the night at one of the more notable among them, the Luna Salada just outside the town of Uyuni. Everything from the walls to the beds to the chairs and tables in the restaurant is made of salt, the effect softened with a rich mix of local arts and crafts.

The next day, we set out for an isolated island of rock known as Isla Incahuasi. This we must do slowly, as the residual surface water is deep enough to cause problems for our vehicle. This is not somewhere you want to break down. Joel tells me he was once stuck out in the Salar for eight hours before being rescued by a passing vehicle.

Distances here are deceptive—Isla Incahuasi appears on the horizon, but never seems to get any closer, even when the water gets shallower and we pick up speed. I spot a fleet of cars in the distance speeding eastward, directly across our path. “Tourists?” I ask Joel. “No,” he replies. “Look, they don’t have license plates—it’s contraband from Chile. Cars are much cheaper over there, so they just drive them over.”

Isla Incahuasi is in fact the peak of an extinct volcano that was submerged by a pre- historic lake. Today surrounded by the searing white crust of the Salar de Uyuni, the rugged outcrop is covered in petrified coral and giant cacti, some of which were here long before the Inca rose to power. It has also become a popular pit stop on the four-by-four circuit and there is a daily influx of tour groups. They clamber around the jagged summit, or tuck into llama steaks at the small restaurant and visitors’ center. Some spill onto the shimmering expanse of salt, where they snap photos with their smartphones and digital cameras.

A decade from now, Bolivian-made lithium-ion batteries could be powering these very same devices; recent contracts with Korean and Chinese companies suggest this might be more than just a pipe dream. There is no doubt that a lithium bonanza would trigger a huge wave of economic and social change in this impoverished country. But gazing out of my window on the drive back to La Paz, I get the sense that this plateau high above the world will retain its timeless atmosphere for thousands of years to come.

The Details

Getting There

Flights into La Paz’s El Alto International Airport—the highest of its kind in the world—are limited to regional and domestic services. Aim to get there via one of South America’s busier hubs: Cathay Pacific (cathay pacific.com) connects to Santiago via Auckland, and to Lima via San Francisco or Los Angeles; Singapore Airlines (singaporeair .com) operates a thrice- weekly Singapore– Barcelona–Sao Paulo routing.

When to Go

Winter in the Antiplano (May to October) brings equatorial heat by day and subzero temperatures by night—but it also means dry, clear weather and more comfortable traveling than during the rainy season. August is the peak tourist month.

Where to Stay

In La Paz, Hotel Europa (64 Tiahuanaco St.; 591-2/231-5656; hoteleuropa.com.bo; doubles from US$175) offers smart, spacious rooms near the center of town, with a spa and heated pool rounding out the amenities. For visits to the Salar de Uyuni, be sure to book a stay in one of the area’s “salt” hotels: Luna Salada (591-2/ 271-3565; lunasalada hotel.com.bo; doubles from US$110), built from blocks of salt, is among the best.

Touring

Southwest Bolivia’s four-by-four circuit is now well established, with numerous outfitters to choose from. The author traveled with Ecuador-based Surtrek (surtrek.com), whose itineraries include eight-day Altiplano tours ranging from La Paz to the Salar de Uyuni.

This article was originally published in the February/March 2013 issue of DestinAsian.