The bedrock of their diet is the olive. Zoe Nowak, an expert in culinary tourism development, likens her homeland to “a never-ending olive grove producing huge quantities of high-quality, extra-virgin olive oil.” Indeed, Cretans consume more olive oil per capita than anyone else on the planet. So, one bright June morning I took a tour of Vassilakis Estate—the island’s oldest olive-oil producer —with Manolis Vassilakis, whose great-grandfather founded the company in 1865. A solemn man with a bush of curly salt-and-pepper hair and sun-burnished skin, Vassilakis guided me around his empty olive mill on the outskirts of the hillside town of Neapoli, pointing out the machines that separate the leaves from branches and other steel contraptions that thrash, dry, crush, blend, mash, and centrifugally separate the oil from the water. Although the factory was in hibernation mode, I could visualize it humming with activity during the November through December harvesting and pressing season.

“In the village where I grew up, there is a rule that when a young boy becomes a man, he has to put an olive tree in the ground,” Vassilakis told me in a contemplative way. “He then has the responsibility to farm that tree for the rest of his life.” The olive, in other words, is more than just food. It is a Cretan’s connection to the land, a pillar of the island’s history and identity.

Falcons hung in the clear blue sky above us as Vassilakis drove me out to see his family’s grove, steering along narrow, precipitous roads so dusty that the jeep’s tires sometimes spun out. “The land here is so steep that you can’t use mechanical equipment to pull the olives from the trees or to spray them with chemicals,” he said as we passed an olive tree growing at a 45-degree angle out of what appeared to be solid rock, its waxy silver-gray leaves glittering in the sun. “You have to tend to them by hand, and that produces higher quality fruit.”

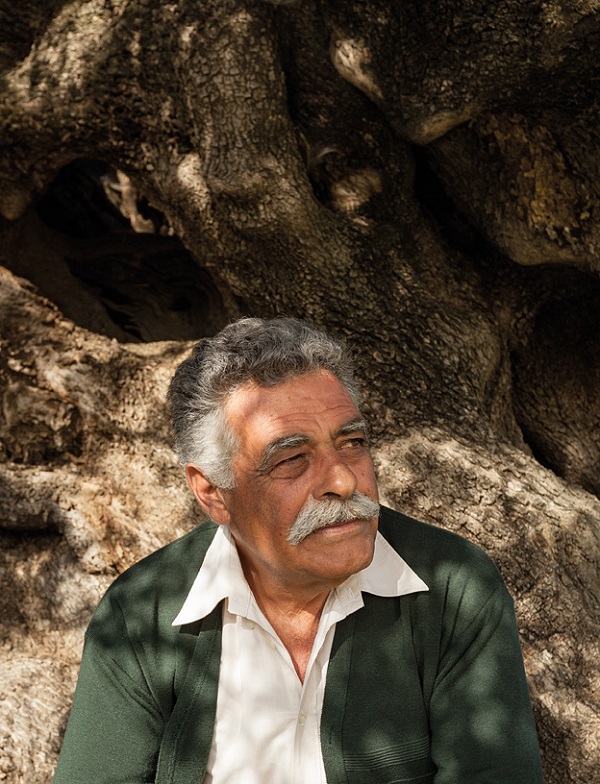

At the grove, he sat against the bole of a gnarled olive tree that he claimed was more than 1,000 years old, and which was still producing fruit. “The olives here are like gold,” Vassilakis said, adding that his estate pressed oil from olives supplied by both its own trees and by farmers located within a 30-kilometer radius. Such is the company’s pride in the provenance of its oil that it stamps a lot number on each bottle. Plug that number into the company’s website, and a Google Earth map pops up showing the field where the olives were harvested along with the name of the producer, the date of bottling, its chemical characteristics, and even which of the factory’s gleaming stainless-steel tanks the oil was stored in prior to bottling.

While Cretan food circa the 1960s helped popularize the Mediterranean diet, Minoan Tastes takes its inspiration from a much more distant past. Founded in 2011 by an American archaeologist, a local anthropologist, and a Jordanian chef, the self-described “cooperative initiative” studies what Cretans ate—and how they ate it—in pre-Christian Minoan times, four millennia ago.

I had lunch with the archaeologist, Jerolyn Morrison, at the aptly named Café Panorama in Platonos, a tiny village perched hundreds of meters above Mirabello Bay. An American from Kentucky, Morrison has lived in this part of Crete on and off for the past 17 years, so I let her do the ordering. She made a beeline for the kitchen, inspecting the various pots and trays before asking the cook what was best.

Back at the table, she told me, “Our interests are in the ancient Cretan kitchen, exploring what it means to share fresh food cooked slowly over a hearth fire in a ceramic pot or in a stone oven. We’re not just a catering company that has a spin on old food; we have an important legacy to leave.”

To that end, Minoan Tastes holds cooking events that re-create long-forgotten dishes from the Minoan era using replicas of Bronze Age pots, amphorae, and utensils. Morrison likens the endeavor to a living museum, with a philosophy akin to that of the Slow Cooking movement.

“When you go to a taverna today that serves Cretan food, many of the dishes are made with New World vegetables from the Americas—tomatoes, squash, potatoes, peppers—or with vegetables from Asia, like eggplant or cucumbers. We believe the Cretan diet of today is poor compared to the food that the ancient people used to farm, collect, hunt, and fish.”

Wherever it fits in the chronology of Cretan food, our meal at Café Panorama was astonishing, highlighted by mezes of dakos (whole-wheat rusks topped with chopped tomatoes, mizithra cheese, olives, and oregano), anthus (zucchini flowers stuffed with lemon-spiced rice and flecks of cumin), and vlita (a wild green steamed and drizzled with olive oil, lemon, and sea salt). Afterward, Morrison took me foraging at Tholos Beach. She waded into the water, pulling limpets from spiky rocks. In fields set back from the shore, she showed me wild thyme, land snails, sundried wild green beans, nascent capers in their smooth buds. She motioned to an arid, rocky stretch between a clump of carob and eucalyptus trees. “In the fall and winter, this entire area turns green. You’ll see faskomilo [sage] and giant caper bushes. Wild asparagus grows in the spring, and mushrooms sprout in the fall.”

All this, I marveled, on one small, unremarkable parcel of land in northeastern Crete.

Crete has produced wine for millennia, from pre-Hellenic times on through successive periods of colonization by the Romans, Byzantines, and Venetians. What is possibly the world’s oldest wine press was unearthed amid the ruins of a Minoan estate south of Heraklion. But two and a half centuries of Ottoman rule brought wine growing on the island almost to a halt, a situation that persisted through the tumultuous decades following Crete’s unification with Greece in 1913.

Today, the island’s wines are resurgent, thanks to a slew of fresh wineries and a new marketing body called Wines of Crete, which formed in 2010 and represents 40 of the island’s vintners. On another cloudless day, under the cover of a bamboo-shaded portico, I met with Nikos Miliarakis, president of Wines of Crete and owner of Minos Wines, the island’s oldest winery. Half-Greek, half-French, Miliarakis is a tall, easy-going man with an erudite demeanor. We sat by a wobbly wooden table surrounded by olive groves and strings of vines at Minos Wines’ vineyard house in the hills outside Peza.

“Cretan wine really changed 15 years ago. That’s when a new generation of winemakers appeared—Greek enologists who had studied abroad, moved back, and brought with them a clearer sense of what the market needed,” Miliarakis explained. “Small wineries began to appear, focused more on quality and limited production.” Supporting that quality is a varied catalog of grapes unique to the island: whites like Dafni, Plyto, Thrapsathiri, and Vilana; reds like Kotsifali, Liatiko, Mandilari, and Romeiko.

I was itching to try some. We started with a Vidiano, a light, mildly sweet white with a spicy finish of cloves. Next Miliarakis poured a crisp Malvazia that hinted of leather, prune, cinnamon, and apple. “I want the notoriety of French or Italian areas but without the heaviness,” he said between sips, slumping his shoulders for effect. I figured he might have already achieved that with his velvety Miliarakis Estate, the red we ended our tasting with: made from Kotsifali and Mandilari grapes, it was peppery, fruity, full-bodied.

Keen to showcase the island’s wines to a wider audience, Miliarakis cofounded Vintage Routes Crete last summer, offering guided tasting tours of Minos and other wineries. “Crete isn’t just a beach destination,” he said. “The inland part is quite beautiful, similar to Tuscany, with excellent gastronomy and many vineyards and other places worth visiting. The real Crete is 15 minutes from the coast.”