Above: Shadow puppeteer Mann Kosal at Phnom Penh’s Sovanna Phum Theatre.

The revival of Cambodia’s performing arts is in full swing

By Robert Turnbull

Among the more notorious achievements of the Khmer Rouge regime was the widespread destruction of Cambodia’s resplendent arts. Faced with Pol Pot’s dictum, “tuk min chamnen, dak chenh ka, min kat” (“to keep you is no gain, to kill you no loss”), artists skilled in a wide variety of music and dance disciplines endured slave labor and famine, not to mention the constant threat of execution. During those long-drawn-out years between 1975 and 1979, it is estimated that 80 percent of the country’s classical dancers perished.

If, ultimately, Cambodia’s artistic traditions endured the worst of mankind’s brutality, it was largely due to the tenacity of the survivors. The alfresco performances that characterized village life in the 1980s were nothing if not celebrations of national pride and the desire for continuity. There was no money: artists were paid in food by spectators leaning against trees or bicycles. Cambodians ached for entertainment. The Khmer Rouge’s preferred form of theater had been the macabre nightly self-criticism sessions, when, to frenzied applause, individuals confessed their “treachery”—and disappeared as a result.

Cambodians are the guardians of an artistic conscience that permeates all levels of society: hardly a holiday, wedding, or funeral isn’t accompanied by a performance of some kind or other. The kingdom can claim around 20 musico-dramatic forms, not to mention a cornucopia of ritual and ceremonial dances springing from Buddhist as well as animist beliefs. Traditional folk dances and musical theater are an essential part of Khmer New Year celebrations in April; there is as well a plethora of festivities related to harvest, such as Bon Om Touk, November’s water festival.

The revival of Cambodia’s performing-arts scene is today in full swing, though most visitors to Siem Reap, the country’s prime destination, aren’t likely to notice. The few events staged here are geared toward tourism. Some, like the French Cultural Centre’s Les Nuits d’Angkor, held at Angkor Wat every December, and the annual light-and-sound show produced by Thai-Cambodian joint venture Bayon CM Organizer, offer busy spectacles that showcase a variety of dance forms. But for the rest of the year, performances are dominated by tour-group buffet dinners during which the chanting of gilded apsaras is all too often drowned out by the clanking of knives and forks.

That said, Siem Reap is the center of a rich shadow-play tradition and the source of at least two different forms of shadow puppetry, or sbaek. The most important, sbaek thom, uses large leather puppets and retells stories from the Reamker, the Khmer version of the Hindu epic Ramayana. With their moving mouths and menacing eyebrows, the smaller sbaek touch are closer in spirit to the Javanese folk theater of wayang wong, from which they derive. The vein is boisterous and comical with slapstick brawls between drunken beer-bellied farmers.

The best of the sbaek thom troupes operates out of Wat Bo, an 18th-century pagoda just north of the Siem Reap River. Coconut shells are lit behind a three-meter-tall screen where players brandish intricately crafted leather vignettes of Rama, Sita, Hanuman, and other mythic heroes. This is authentic Cambodian theater: magical, low-tech, atmospheric.

Still, one must head to Phnom Penh to fully appreciate the country’s artistic renaissance. The capital has seen strands of an integrated cultural life come together through grassroots activities led by an amalgam of surviving dancers, musicologists, and the handful of politicians committed to laying the framework for more enduring artistic activity. Several foreign producers have catalyzed the process, introducing modern trends in stage management and technical direction—not to mention expertise in fundraising and marketing.

The great dance-dramas that form the kernel of the classical repertory are an obvious priority today. The pinnacle of these is, once again, the lengthy Reamker epic. The key figure here is Princess Norodom Buppha Devi, eldest daughter of former king (now “King-Father”) Norodom Sihanouk. An accomplished dancer in her youth, she once enchanted French president Charles de Gaulle with her rendition of the Robam Apsara, a dance created by her grandmother Kossamak Nearireath. Based on images of the celestial nymphs depicted on the country’s temples, the 15-minute-long Apsara, along with Angkor Wat itself, soon became the symbol of Cambodia abroad.

It was Princess Buppha Devi, now 65, who presided over the long and painstaking process of documenting classical dance techniques, hitherto preserved only in the fragile memories of old masters and passed on by word of mouth. Numerous dances have since been rescued for posterity, with as many as 4,000 gestures recorded on paper and video. “We had to act before any more elderly dancers became ill or passed away,” says Proeung Chhieng, the dean of choreographic arts at Phnom Penh’s Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA).

RUFA is where it is all happening, and the process is heartwarming to watch. The university’s undergraduate program is being relocated to the campus behind the famous terracotta-roofed National Museum, and should soon be accessible to tourists. Until that happens, travelers who want to see mentorship in action should visit the headquarters of the Apsara Arts Association, located near the University of Phnom Penh. There, wasp-waisted young girls with vermillion lips and dressed in gorgeous silk sampot (wrap skirts) go through their paces, adopting the graceful hand gestures of classical dance to the dulcet tones of the pinpeat, an orchestra of reeds and gongs. Knees bend, buttocks protrude, fingers stretch. It’s a beautiful image. Every Saturday night their tiny bodies are literally sewn into elaborately bejeweled and sequined bodices and richly patterned sampots for public performances. Around their ankles and wrists are gold bangles, and their headdresses are crowned with frangipani flowers.

Another NGO, Amrita Performing Arts, has done more than any other organization to raise the level of professionalism among Cambodia’s new generation of dancers. Much of the credit for this goes to its founder, former American opera director Fred Frumberg, who came to Cambodia in 1997 as a consultant with UNESCO. Frumberg has been pivotal in raising funds to help remount classics and stage coproductions with other regional organizations. Last summer’s debut of Sovannahong, which ran for a single night at the riverside Chaktomuk Theater, was financed largely by the Rockefeller Foundation. The ballet, a story about a princess who mutates into a man in a desperate quest to bring her slain lover back to life, was first choreographed in 1955, but only recently reconstituted under the direction of Princess Buppha Devi.

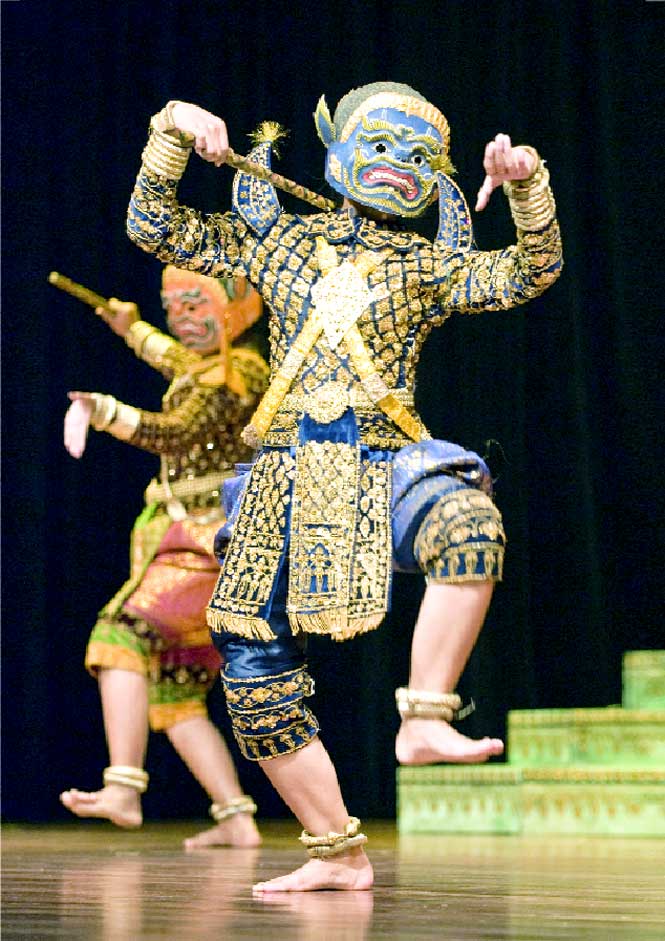

Spectacular though it is, classical ballet represents just one facet of the country’s performance culture. Amrita’s inventive and varied program includes revivals of lakhon niye, (speaking theater), Cambodian circus and folk dance (roban propayni), yikai (traditional theater accompanied by percussion), and bassac (a popular form of music-drama closely related to Chinese opera). Amrita’s production of Weyreap’s Battle toured London and opened the 2006 Melbourne Festival. The idiom was lakjoan kaol, a male masked-dance version of the Ramayana that emerged in the early 1900s as an alternative to the royal palace’s centuries-old female counterpart (robam borann). Huge set pieces, richly colored masks, and aggressive masculine movements make for a fascinating contrast to the more graceful female version.

Increasingly confident younger artists are also exploring the relationship between contemporary performance and the rich and disciplined traditions they have trained in. Modern theater is the form that most easily conforms to these ideals, but there are now efforts to bring classical dance into this process. The Khmer Arts Academy, a company set up by Sophiline Shapiro, a former palace dancer who emigrated to California in the late 1980s, was a collaborator in the commissioning of court-dance interpretations of Shakespeare’s Othello (Semritachak) and of The Magic Flute (Pamina Devi). The KAA has had considerable success abroad, and can be credited with creating the first classical ballet outside the often-stultifying influence of the Ministry of Culture.

The French-Cambodian NGO Sovanna Phum (“Golden Era”), which operates out of a humble open-air theater on Street 360, is unique in offering regular weekend performances of both traditional and contemporary creations. Run by shadow puppeteer Mann Kosal, it specializes in hybrid and highly accessible reimaginings of Cambodian myths through shadow puppetry, classical and modern dance, as well as drumming and other disciplines.

For its part, Cambodian Living Arts (CLA) has been working with musicians, largely instrumentalists and singers famous before the civil wars for genres that currently fall outside the classical umbrella. The organization supports 16 elder masters in numerous programs focusing on performance, teaching, and recording. Each receives a stipend, medical care, and the opportunity to earn well above the average national wage in return for master classes and performances to the public and donors. As many as 300 pupils benefit.

CLA’s extensive revival of near-extinct instruments has excited musicologists. In northeast Ratanakiri, the group managed to mobilize the only surviving player of the memm—a primitive stringed instrument in which the sympathetic string is held between the teeth—to tutor more than 20 students in this remote and densely forested province. CLA also supports players of the ancient Angkorian one-stringed ksadiev, which high-profile singer and dancer Ieng Sithul and his 25-strong troupe introduced to the 2007 WOMAD festival in England.

More recently at the Chenla Theater in Phnom Penh, CLA and Amrita premiered Where Elephants Weep, an ambitious rock opera based in part on the folkloric tale Tum Tieuv, a story of doomed love between a palace-educated monk and a village girl that is often referred to as the Khmer version of Romeo and Juliet. Using both traditional and modern instruments, the US$800,000 show proved so successful that it is likely to return by popular demand.

It’s all part of a thriving artistic community that Fred Frumberg attributes to hard work and gentle nurturing. “Cambodian dancers and actors are now getting a glimpse of a better future,” he says. “I just hope that more people take the time to see what our efforts have produced.”

Originally appeared in the February/March 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Out From The Shadows”)