Above: A high peak in the Baba Budan Hills.

Cradled in the highlands of southwest Karnataka, Chikmagalur is cultivating a reputation for its cool climate, verdant mountain scenery, and growing range of lodgings. But for one caffeine aficionado, the main perk of any visit is the coffee

By Shoba Narayan

Photographs by Matthieu Paley

Hiking up the lush Baba Budan Hills of Karnataka, carrying little more than a flask of freshly brewed coffee. It’s a bright February morning and the temperature is hovering around 20°C, perfect conditions for a scenic ramble in the mountains. But for caffeine-loving me, this is as much a pilgrimage as a nature walk, for it was on these slopes that South India’s favorite beverage first burst forth. As the late, great Tamil novelist R. K. Narayan once noted, “The origin of Indian coffee is saintly. It was not an empire builder or a buccaneer who brought coffee to India but a saint, one who knew what was good for humanity.”

Narayan (no relation of mine, alas) was referring to the 17th-century Sufi mystic Baba Budan, who, returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca, encountered coffee at the port of Mocha in Yemen. Beguiled by its taste, he spirited away seven seeds in his waistcloth, brought them back to India, and planted them in the hills that now bear his name, perhaps along the very trail that I’m following.

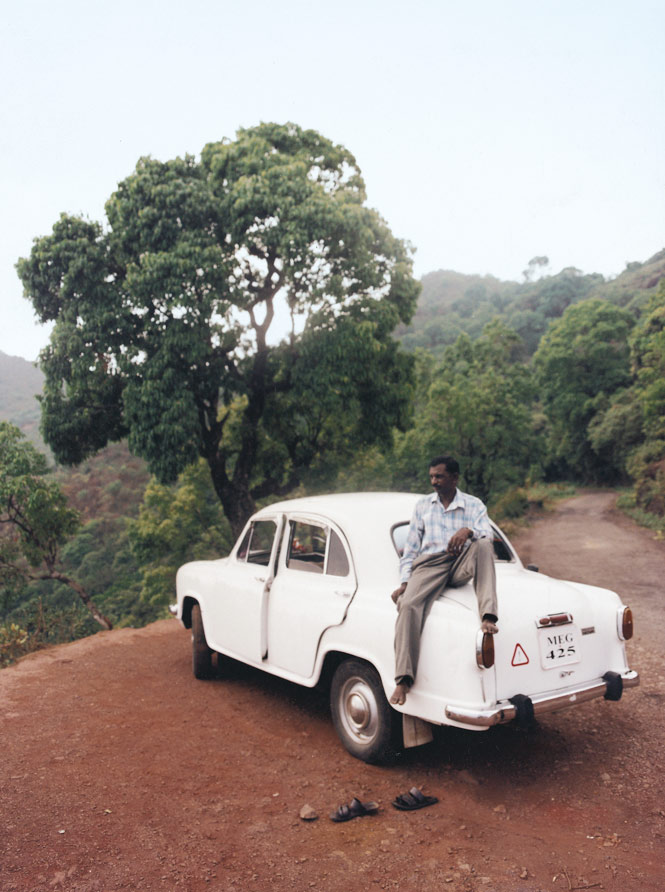

That thought makes me smile as I plow uphill along a narrow track that winds through coffee estates. Most of Karnataka’s coffee is shade-grown, which means the estates appear more forest than farm. Above me, sunlight filters through a canopy of rosewood, ficus, and silver oaks onto the arabica and robusta bushes that carpet the hillsides. Birdsong fills the air, as do the scents of wet earth and eucalyptus. I spot barefoot villagers balancing deadwood on their heads as they pick their way downhill; occasionally, college students bound past in sweatpants and sneakers. There are waterfalls and burbling mountain streams. And through the trees, I can see cars winding their way up a distant road toward the summit.

An hour later, I reach the top of Mullayangiri, which, at just shy of 2,000 meters above sea level, is the tallest peak in Karnataka. On its crest is a tiny Shiva temple, complete with a saffron-clad priest. After murmuring a quick prayer, I perch on a ledge and gaze down at the undulating green hills arrayed around me like the folds of a sari. I take a triumphant sip of coffee. The aroma draws jealous stares from a nearby group of sightseers.

For those of us raised south of the Vindhya Mountains, coffee is not just a beverage, a brew, a cup of joe. It is a life-enhancing elixir; as much a part of the South Indian psyche as Kanjivaram silk saris, Carnatic music, and coconut-laced curries. In My Dateless Diary, a chronicle of his trip to the United States in the 1960s, R. K. Narayan recounts ordering a cup of coffee in a New York café. “Black or white?” he is asked. “Neither,” he replies haughtily.

“I want it brown, which ought to be the color of honest coffee. That’s how we make it in South India, where devotees of perfection in coffee assemble from all over the world.”

Narayan, who used to call himself “the globe’s best coffee taster,” wasn’t exaggerating. Just as preparing a good pot of tea is a British obsession, coffee holds an almost mythic sway over the South Indian subconscious. This isn’t espresso as the Italians have it, or Turkish coffee so thick you can stand a spoon in it. Nor is it watery café Americano. In Karnataka, as in the neighboring states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, people drink “filter kaapi”—an aromatic decoction the color of dark chocolate, chicory-leavened and dripped through a perforated brass or stainless steel filter, served with a dash of frothy hot milk and just enough sugar to remove the bitterness.

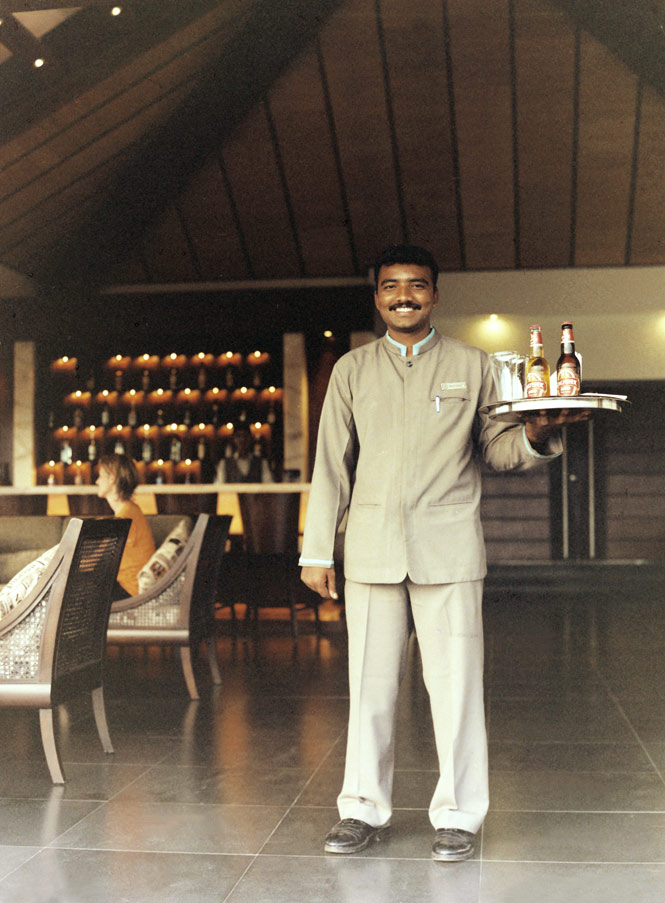

The Indian gentleman at the table next to me at The Serai, however, is sipping a milky chai tea, as sure a sign as any that he’s from the north. Poor thing, I think as my decanter of coffee arrives. He doesn’t know what he’s missing.

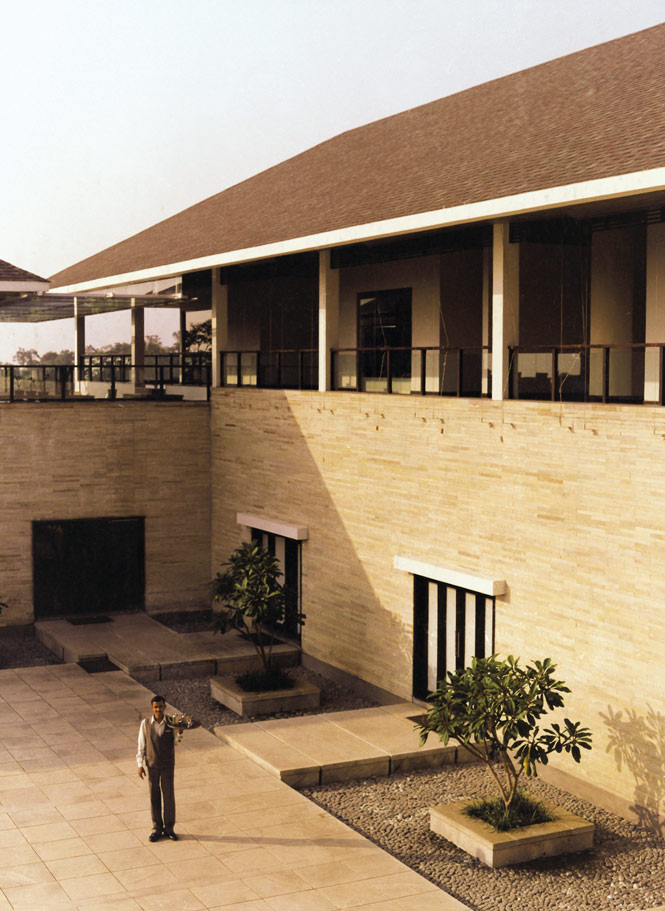

But he does know how to choose his accommodations. The Serai is a new resort outside Chikmagalur, a hill town of some 100,000 people situated smack in the middle of Karnataka’s coffee country, about a five-hour drive from my home in Bangalore. It is owned by the Coffee Day group, whose chain of cafés—789 at last count—has emerged over the last dozen years as the local equivalent of Starbucks, minus the stigma. Situated on one of the company’s coffee plantations, The Serai is what Bangalore software engineers might approvingly call “vertically integrated”: its superb coffee comes straight from the surrounding estates; the rosewood floors in the 30 tropical-minimalist villas were fashioned from dead and fallen shade trees; and the activities program includes plantation walks.

I’m shown to my villa by a smiling young man named Vijay. Set on two levels with a small attached pool, my lodgings are larger than the Upper West Side apartment where I once lived in Manhattan. In addition to the usual trappings of luxury—king-size bed, silk cushions, flat-screen TV, white linens that manage to be both crisp and soft—there are picture windows framing soothing greenery and a cavernous bathroom with a pebbled outdoor shower. The tea-scented toiletries strike me as a misstep, but every other detail seems well thought out.

Chikmagalur—the name of both the town and the district that surrrounds it—grew up around the coffee trade, which began in earnest here (and in the highlands of Coorg, 185 kilometers to the south) in the mid-1800s with the arrival of European planters. It’s a sleepy place with a hodgepodge of buildings; fertilizer depots and trading offices line the main roads, while processing factories and garbling sheds pepper its outskirts. But even here, you can feel the reverberations of Bangalore’s economic boom. Over the past few years, coffee planters have begun converting their massive bungalows into homestays that cater to free-spending young techies who drive down for the weekend. The Serai, however, is the area’s first upscale resort.

The next morning, I gorge on fresh fruit, croissants, hot masala dosa (savory crepes), and countless cups of coffee at the breakfast buffet. Then, after making an appointment at the spa for an afternoon massage, I set off in one of the resort’s jeeps for a guided tour of the surrounding property.

Coffee estates can be experienced on many levels. For those who seek nothing beyond postprandial exercise, the plantations afford a pleasant walk amid coffee shrubs that, depending on the season, are bright red with berries, snow-white with flowers, or an eye-cooling green. On my visit, the coffee berries have just been harvested. Lithe young men wearing nothing but dhotis shinny up the shade trees and cut away branches to let in more sunlight for next season’s growth. Other workers are daubing a white paste around the base of coffee plants to guard against pests. Women with colorful headdresses and bamboo baskets scour the bushes for any remaining berries, leaving their toddlers to play in the sand at their feet.

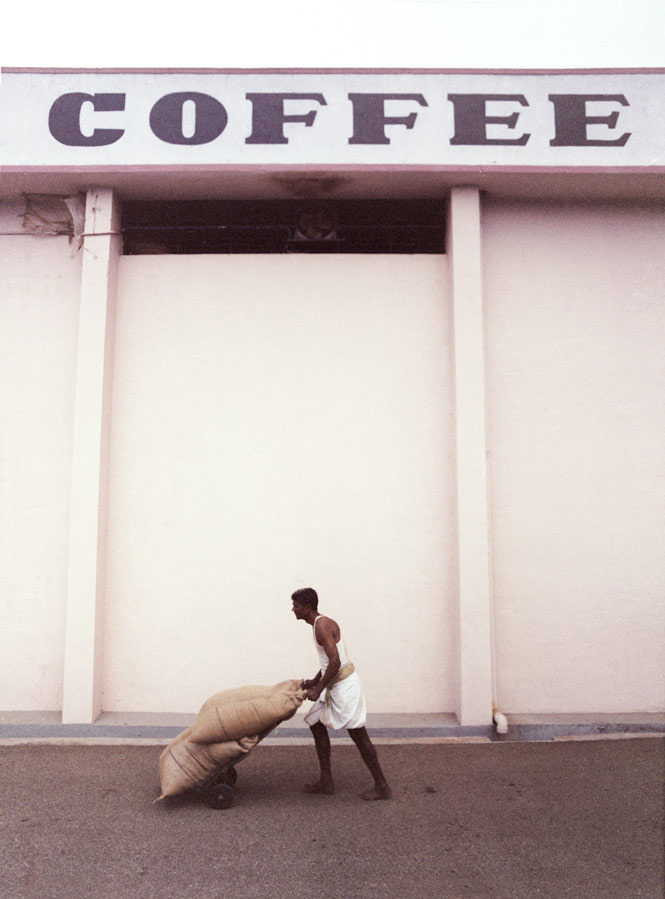

At Kudregundie, a nearby estate owned by The Serai’s parent company, I’m introduced to Dr. Sreenivasan, a horticultural consultant with magnificent Albert Einstein eyebrows and an encyclopedic knowledge of coffee. He talks to me about bugs and soil erosion and the efficacy of a weed called—at least according to my notes—Uryinaria cordat, which he extols as an admirable ground cover. He also explains that Chikmagalur, along with the districts of Hassan and Coorg, accounts for almost 75 percent of coffee production in India, which is in turn among the world’s top 10 producers of the bean.

Yet while its recent history is rooted in coffee, Chikmagalur can look back on a much more glorious past. It was once part of the mighty Hoysala Empire that ruled over a wide swath of southern India between the 10th and 14th centuries. The Hoysalas were great warriors, but more than that, they were patrons of the arts and architecture, building stunning temples in nearby Belur (their erstwhile capital) and Halebid. Chikmagalur was, in fact, part of the wedding dowry of the younger daughter of a Hoysala chieftain. In Kannada, the local language, its name literally means “younger-daughter town.” (Nearby Hiremagalur, or “elder-daughter town,” was presumably given as dowry for her older sister.)

Three types of tourists gravitate toward this area. History buffs come to admire the Hoysala temples, which, though filled with the usual curvaceous nymphs and elephants of Hindu lore, present a dazzling geometry of design. Adventure buffs rock climb, rappel, or hike up hills with musical names like Kemmangundi (“Red Earth Valley”) and Kudremukh (“the Horse Face”). Pilgrims base themselves in Chikmagalur town and make day-trips to the famous temples in Sringeri, Horanadu, Kalasa, and Amruthapura. Coffee maniacs like me, it seems, are the exception.

Later that afternoon, after a relaxing aromatherapy massage that leaves my skin as soft as coconut pulp, I visit Chikmagalur’s Coffee Museum. It turns out to be an uninspired place with one redeeming feature: a superb documentary on coffee by acclaimed Indian filmmaker Santosh Sivan. Charts on the wall tell me about South India’s specialty coffees, none of which I can sample locally because they are all exported. Monsooned Malabar, a docent explains, is made by storing the beans in sacks and exposing them to humidity. “Very popular in Scandinavia because they like lighter coffees,” he adds. Can I buy some in town? “Not available, madam.” Also unavailable is the unfortunately named Mysore Nuggets, or any of the organic coffees displayed in tiny glass bins as raw coffee beans. “Try the specialty stores in Bangalore,” the docent suggests half-heartedly.

Above, from left: Unloading coffee beans at a factory; removing bad beans prior to roasting; highland scenery.

Bangalore and Chennai, the state capital of Tamil Nadu, are where the art of South Indian coffee reaches its acme. In both cities, countless cafés pour shots of first-rate coffee to a devoted, if opinionated, clientele, each of whom has a view on what constitutes a good brew. In Bangalore, Dakshin at the luxurious ITC Windsor hotel serves very good filter coffee in silver tumblers, albeit at five-star prices. At the other end of the spectrum, Brahmin’s Coffee Bar, a tiny self-serve eatery near the Bull Temple of Basavanagudi, offers excellent coffee for pennies, while some swear by the Mavalli Tiffin Room, where generations of Bangaloreans have ducked in after taking a morning walk at the nearby Lalbagh Botanical Garden.

In Chennai, too, good filter coffee can be had at pretty much any hole-in-the-wall eatery. Roadside stalls also do what we affectionately call “meter coffee.” The vendor will mix the coffee and then pour it in dramatic arc-like motions between two stainless steel tumblers, much like his teh tarik (“pulled tea”) counterparts in Singapore and Malaysia. This serves to cool the beverage down and add a layer of froth on top; it has the added benefit of putting on a good show for customers.

But the best coffee, everyone agrees, is to be found in homes, especially planters’ homes. And while that may not sound like particularly helpful advice to travelers looking for a caffeine fix, it’s actually a straightforward proposition. In the last few years, with coffee prices turning volatile, more and more planters in Chikmagalur have opened their bungalows to paying guests.

I am headed to one of them. It is called the Thippanahalli Home Stay, and I’ve chosen it because it is brand new. The quality of Chikmagalur guesthouses—and I’ve stayed at many over the years—varies widely. Some charge per person and cater to price-conscious bachelors who spend all day hiking the backcountry and come “home” just to sleep. Others lure honeymooners with promises of solitude, comfort, and good food. Some, like Thippanahalli, prefer families and reserve the right not to admit “hard-drinking bachelors who stay up all night and scare the owls,” as my host delicately puts it.

Thippanahalli is owned by Ravishankar Araluguppe and his wife Meera, fifth-generation planters who are happy to share stories of their life on a coffee plantation. Their “bungalow” turns out to be a two-story red-brick mansion built in the 1930s. It’s a rambling affair with a colonnaded porte cochere out front, a tranquil courtyard out back, and 28 rooms filled with antiques and memorabilia, including a Bohemian chandelier, Chinese wall hangings, and, most interesting of all, a neatly drawn Araluguppe family tree going back to the 18th century. The house is beautifully maintained and fronted by manicured lawns lined with flowering shrubs and—improbably in this cool region—an enormous cactus.

After freshening up, I head to the small dining room for lunch with the Araluguppes. The food is excellent. Unlike at The Serai, the menu here incorporates local specialties that are hard to find outside private kitchens. Meera starts us off with dollops of chutney and akki roti, a flatbread of rice flour, shredded coconut, chopped onion, cilantro, and green chilies, sprinkled with cumin seeds. (Unlike dosas, which are spread on the pan using a ladle, akki rotis are typically hand-patted, a technique that leaves impressions of the cook’s fingers in the dough. It’s a personal, handmade touch that I find delightful.) We also have balls of steamed rice known as kadubu, which we dip in a gravy made from horsegram, tamarind, and freshly ground pepper, and Meera’s specialty: engai palya, a tangy dish of bell peppers stuffed and simmered with spices.

Above, from left: Room service at The Serai; chicken simmered in coconut milk and dry chilies, at The Serai; one of The Serai’s two-story villas; cocktail hour at The Serai’s lounge.

Later that afternoon, after sampling my hosts’ coffee, I hike into the foothills of Mullayangiri. It’s a bracing walk that makes me feel better about overindulging at lunch. When I return, a campfire has been built. The other guests are honeymooners who don’t show up except for rushed meals. I sit with Ravishankar and catch up on the local gossip before turning in.

It is not, alas, a good night’s sleep. Owls hoot, dogs bark, and, even more infuriating, the night watchman feels compelled to ring a bell every hour. Ravishankar confesses sheepishly the next morning that this is on his instructions, something to ensure that the man stays awake during his vigil. Trying to make amends, he arranges for me to visit the Kadur Club, a members- only hangout founded more than a century ago by British planters. I recommend it only to the most die-hard coffee historian. Though the membership now is wholly Indian, it remains a mothballed testament to—to what? A time when managing coffee plantations was still an elitist occupation, I suppose. In the half-timbered bar, the walls are covered with faded photographs of long-dead revelers; in a dining room accessorized with a grandfather clock and a stuffed gaur buffalo head, waiters in starched jackets still serve roast chicken, bread-and-butter pudding, and “white soup.” Amid the ghosts of the Raj, even the coffee tastes stale.

During the long drive back to Bangalore, I stop at some of the smaller Hoysala temples en route. Their cool interiors and carved black granite columns seduce me with their beauty. Villagers point me to a tiny temple of the monkey god Hanuman, and on impulse, I visit it too.

Heritage: check. Hikes: check. Temples: check. I register with satisfaction that I have accomplished all the things that travelers come to Chikmagalur for. Plus, I have sampled some very good coffee. But I have one more cup to go. Two hours outside Bangalore, I stop at a Coffee Day café right beside the highway. My filter coffee arrives: dark, aromatic, piping hot. Blowing gently on its frothy cap of milk, I silently raise a toast to Baba Budan—saint, smuggler, and, like me, someone who evidently appreciated one of life’s simple pleasures.

THE DETAILS:

Chikmagalur

Getting There

Bangalore, the gateway to Karnataka, is well connected by air to other major cities in India. Internationally, Singapore Airlines (singaporeair.com) flies daily to Bangalore, as does Dragon Air (dragonair.com) from Hong Kong. The 250-kilometer drive to Chikmagalur takes about five hours.

When to Go

Chikmagalur’s cool climate is pleasant year-round, even during the June–September monsoon season, when the scenery is at its most lush.

Where to Stay

By far the best accommodation in the area is at The Serai (KM Rd.; Mugthihalli; 91-8262/ 224-903; doubles from US$185, including breakfast), where 30 modern villas, some with private pools, are set amid a working coffee estate. The resort can arrange

everything from plantation tours to highland treks and jeep safaris to the Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary.

Chikmagalur is also home to many bed-and-breakfasts operated out of planters’ houses. The newest and most inviting is Thippanahalli Home Stay (91-8262/210-730; thippanahallihomestay.com; doubles from US$82), where you can stay in either the main residence or in comfortable outlying cottages.

For stopovers in Bangalore, consider staying in either the heritage wing of the sprawling, century-old Taj West End (Race Course Rd.; 91-80/ 6660-5660; tajhotels.com; doubles from US$250) or at the faux-historic Leela Palace Kempinski (23 Airport Rd.; 91-80/2521-1234; theleela.com; doubles from US$470), home to 358 rooms, Bangalore’s best sushi, and a high-end shopping arcade.

Originally appeared in the August/September 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine ( “Mountain Magic”)