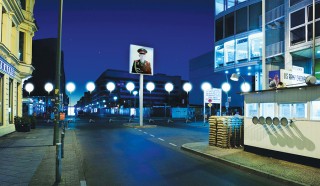

Berlin is clearly not a city that shies away from displaying the horrors of its past, and Mitte is full of reminders of the terrors of the Third Reich, from the interpretative displays periodically set up at Alexanderplatz, the area’s Soviet-style central square, to plaques on houses commemorating their erstwhile Jewish inhabitants and the somber concrete blocks of the Holocaust memorial near Brandenburg Gate, below which an underground gallery painstakingly documents the lives of Jews who died in the war.

The Holocaust Memorial was one of many reunification projects that took place in Mitte during the aughties. Another is the ongoing restoration of Museumsinsel, or Museum Island, an islet in the Spree where five museums were built by royal decree beginning in the 19th century as a “district dedicated to art and antiquities.” The buildings were badly damaged during World War II and further neglected under Soviet rule, and their restoration, says curator Julien Chapuis, represents the most expensive public investment in art and culture in Europe.

With a soaring cupola and a marble-clad entrance hall overseen by a bronze statue of Duke Frederick William astride a handsome steed, the neo-Baroque Bode Museum re-opened in 2006 after a US$200 million restoration. Among its priceless holdings is the world’s most extensive collection of Byzantine sculptures. A stone’s throw away, the Neues Museum, best known for its bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti, followed suit in 2009 after a similarly extensive facelift by British architect David Chipperfield. The Pergamon Museum, which holds archeological relics unearthed during German excavations in Anatolia and Mesopotamia at the end of the 19th century, is currently undergoing a multimillion-dollar upgrade of its own. It treasures include a reconstruction of ancient Babylon’s Ishtar Gate.

The stately museums are in stark contrast to Mitte’s earlier life as a commune for squatting artists, who have since moved out to the grittier precints of Neukölln and Wedding. But art is still Mitte’s biggest asset, particularly in the form of nonprofit galleries. One of the best of these is the Boros Collection, which opened in 2008 in a former bunker designed by the Nazi architect Albert Speer. The five-story fortress, its reinforced concrete walls two meters thick, has since had several incarnations: as a jail for West German soldiers, a depot for Cuban fruit, and as a venue for hard-core dance and sadomasochism parties. Bought by Polish advertising executive Christian Boros a decade ago, the building now houses his vast collection of contemporary art.

Unassuming and un-signposted, the 80-room Boros Collection offers a rich and varied encounter with the obscure and extreme. There is a set of Olafur Eliasson’s Icelandic driftwood logs plonked haphazardly in the twisting entrance tunnel. Ai Weiwei’s Tree crowds a concrete cubical, its sturdy blackened limbs collected from dead camphor trees and bolted together using ancient Chinese joinery techniques. A statement against the breakneck speed of development in China—and how the environment pays the highest price—the gangly piece of art appears even more ominous being claustrophobically squeezed between three concrete walls. Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno’s Flying Garden nets illustrate what he believes cities would look like if they were detached from the ground. A popcorn machine, powered by a hair dryer, spills roasted popcorn onto the floor of one room while the humming and ticking of a train-station clock resonates through the concrete walls downstairs. There are no curators; artists are encouraged to install their works in the bare gray rooms as they feel fit.

A few blocks over, the excellent Me Collectors Room, founded by former Wella chairman and obsessive collector Thomas Olbricht, features rotating exhibits on its first floor and Olbricht’s very own cabinet of curiosities upstairs. His Wunderkammer is fascinating, in a macabre sort of way: a coconut-wood chalice adorned with carvings of Brazilian cannibals; a shrunken skull from Ecuador; and a miniature 17th-century anatomical model of a pregnant woman, complete with removable organs and fetus.

On my last night in Mitte, I meet up with some old Berlin friends for dinner at Der Hahn ist tot! (“The Rooster is Dead!”), a local haunt that Tidefjärd recommended as proof that in Mitte, the bohemian spirit lives on. Run by an amiable group of gay friends, the cute little restaurant serves four-course country-style meals for the bargain price of about US$25 a head. In true Berlin style, the food could do with some work—portions are big, meaty, a trifle stodgy. But it’s reassuring to know that something of Mitte’s old flavor still survives.