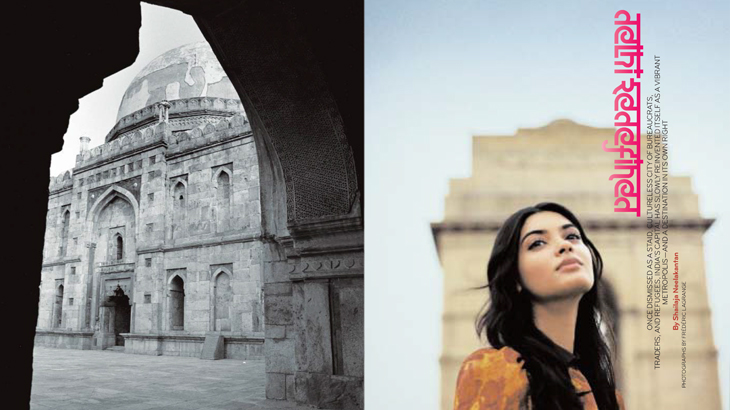

Above: Striking a pose in front of India Gate, a World War I memorial in Lutyens’ Delhi.

Once dismissed as a staid, cultureless city of bureaucrats, traders, and refugees, India’s capital has slowly reinvented itself as a vibrant metropolis—and a destination in its own right

By Shailaja Neelakantan

Photographs By Frédéric Lagrange

Seven years ago, when my husband and I quit our mind-numbing jobs in Hong Kong and decided to move to New Delhi, I was terrified. Although I’d grown up in India and made my start as a reporter in the capital’s boisterous back alleys, I had left there to live in New York for the better part of a decade. I’d gone soft. And unlike my husband, who had come up with the whole crazy plan after reading City of Djinns, British author William Dalrymple’s riveting account of Delhi in the late 1980s, I knew what I was getting into.

After being badgered for a few weeks, I gave in. I summoned up the best yarns from my time covering the lower courts for the Indian Express newspaper. I reread City of Djinns. Finally I convinced myself—at least until we were on the plane—that Delhi would be an adventure.

Up in the air, it all became suddenly, crushingly real. Delhi was a horrible place. On a brief visit in 1996 I had found it clogged with pollution and chock-full of aggression. (And they say New Yorkers are rude!) I had vowed never to go back. Somebody stop the plane, my inner voice screamed. I want to get off.

But something funny has happened to me since I moved back here: belatedly, I’ve come to see the charms of the place. I realized this not long ago, when I made my first-ever trip to Lodi Garden, Delhi’s answer to Central Park. It was a crisp afternoon in the waning days of winter. I’d gone to meet Yoav Bar-Ness, an American Fulbright scholar and an expert on the city’s trees, for an article that I was researching.

On the ride over, I focused on the usual things—the blaring car horns, the cows, pye-dogs, and beggars dodging traffic. Yet as Bar-Ness clambered over the monuments of the 500-year-old garden complex, I finally realized the enormity of what I had been missing. Though I’d spent so much of my adult life in Delhi, I’d never really caught the vibe. But there in Lodi Garden, surrounded by manicured lawns and the magnificent tombs of long-dead emperors, I finally started to understand the magic of the place.

A city of contradictions—of abiding traditions and stunning modernity, of vulgar wealth and shameful poverty, of urbane culture and mercenary crassness—Delhi can be a hard place to love. But its rich history and surprising latter-day charms more than make up for these shortcomings. Conquered by the Mughals, colonized by the British, and reinvented by refugees after independence and Partition in 1947, the Indian capital combines Central Asian machismo with Hinduism’s spiritual sensuality, the colonial addiction to bureaucracy, and the dispossessed migrant’s readiness to fight for a share of the spoils.

“Some people are very aggressive, but others are very kind,” says author Aravind Adiga, who dedicated his Booker Prize–winning novel, The White Tiger, to the people of Delhi. “I’ve fought bitterly with an auto-rickshaw driver over the fare, and cursed him for being avaricious and rude, only to turn around and see him helping a blind man across the road.”

The competition for everything is still fierce in this metropolis of 16 million people. But unexpected moments of kindness aren’t the only compensation. Even though hundreds of thousands of new migrants continue to move to Delhi every year into ever-expanding slum dwellings, the city has a remarkable number of parks and forests. Roads are built around trees that envelop the remains of ancient Hindu and Muslim shrines. Sites like the Red Fort, the Jama Masjid, and Humayun’s Tomb, which were built by Mughal emperors in the 16th?and 17th?centuries, and even older monuments like the Qutub Minar, a towering brick minaret erected by the 12th- and 13th-century rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, rank among the country’s architectural wonders. The crowded bazaars of Old Delhi—best explored in the early morning—offer an immersion into the unfamiliar that borders on the profound. And in posh New Delhi, the capital district founded in the final decades of the British Raj, burgeoning wealth has spawned a thriving bar and club scene. No other city offers more varied or better quality Indian food, and in recent years fine dining has slowly fought its way out of the air-conditioned restaurants of the city’s five-star hotels.

At first glance, Delhi is an ugly sprawl, perpetually crumbling, perpetually under construction. Nearly all the major roadways are flanked by towering cranes, cavernous pits, or tremendous pylons, as the city scurries to complete dozens of Metro rail stations and flyovers ahead of the 2010 Commonwealth Games. The skyline is a brown horizon of flat concrete roofs, littered with the great black water tanks that Delhiites rely upon in lieu of a competent water authority. There are no skyscrapers, no flashing neon signs. Thickets of electric wire and telephone cables loop perilously between the buildings, themselves covered in a thick layer of dull, brown dust. But if you keep your mind on the city’s history and strike out through its winding byways, a very different place unveils itself.

“It is like Rome!” exclaims my friend Peter Nagy, a New Yorker who relocated to Delhi in 1990. In 2003, he opened the Nature Morte art gallery, part of the city’s still unacknowledged renaissance. “I like driving around and seeing chunks of ancient monuments peppering the landscape. And Lutyens’ Delhi is a modern masterpiece,” he says, in reference to the stately government buildings, radial parkways, and grand monuments at the core of New Delhi, laid out by British architect Edwin Lutyens in the 1910s and 1920s. “The Secretariat, the Rashtrapati Bhavan [Presidential Palace]—they’re amazing. The entire capital is; there’s nothing quite like it.”

Fresh from my trip to Lodi Garden, the centerpiece of which is an enormous dome and ruined mosque, I knew exactly what Nagy was talking about. When you live here, it is easy to forget Delhi’s ancient past, because it has been so thoroughly integrated into the present. In no other place will you find so many archaeological wonders just “lying around,” as Dalrymple, who has lived here for the better part of 20 years, tells me one day. “Anywhere else, a city like this would be all tidied up and people would have to buy a ticket to see it,” he says. “But here, people are living their lives around this extraordinarily beautiful stuff.”

Though it does have a ticket booth, one prime example is the Lal Qila, or Red Fort, which lies on the very edge of Old Delhi, across from the teeming spice, silver, and food markets of Chandni Chowk. Despite its obvious historic value as the royal seat of the walled city built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in the 17th century, part of the fort was used by the Indian army until 2003, after which it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. And even now, most of the denizens of Chandni Chowk putter past the massive edifice on motorcycles and scooters without sparing it a second look.

The same is true of Humayun’s Tomb, the 16th-century mausoleum of Delhi’s second Mughal emperor, which lies between a slum and railway station in Nizamuddin. Other marvels—such as a huge mosque and the remains of the palace built by the eccentric Sultan of Delhi, Muhammad bin Tughlaq, in Begumpur—have been even more thoroughly integrated into city life. These ancient places are “now used by men to take a shit,” as Dalrymple eloquently puts it. Built on and around the remains of at least seven different cities, present-day Delhi is a palimpsest, a work in progress. Like the brash new India, it neither reveres its past nor seeks to forget it.

The choked lanes of Old Delhi, too, are a sort of living, moving, and evolving museum of traditional culture. In the frenzied Kinari Bazaar, a maze of tinsel-covered alleys hardly three meters across, rich and poor rub shoulders in tiny shops selling saris, bangles, and anklets for new brides. It’s as much a treasure hunt as shopping. But the treasures are there, says Ritu Kumar, a designer who at age 64 remains a stylish doyen of Indian fashion.

“You get amazing textiles and fun jewelry and wild bags and lots of clothing accessories actually meant for the theater, but you can put it together and make a great outfit,” she told me, gushing. “If you’ve got a fetish for bangles, Kinari Bazaar is your place.”

When I watched Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s recent movie Delhi-6, a tribute to the old city, I realized that the Bollywood attention also reflects my hometown’s changing role in India’s collective consciousness. Once denigrated as a cultureless town of traders and Punjabi refugees—a down-market Washington, D.C. to Mumbai’s glittering Manhattan—Delhi has, over the past decade against all odds, become hip.

“Something happened around the middle of the 1990s,” says Vinod Mehta, editor of Outlook, one of India’s top news magazines. As the economy flourished, the city of bureaucrats slowly became a city of entrepreneurs and intellectuals. “As money flowed in, a lot of talent began moving to Delhi. Take publishing, for instance. Except for film magazines, it’s all moved from Mumbai to Delhi,” he says.

Now, the city becomes more cosmopolitan every day as brave restaurateurs open Italian bistros and sushi bars, aesthetes cram new art galleries into gargantuan South Delhi houses, and designers take over urbanized villages with chic boutiques. But there’s also an enduring character. In some ways, Delhi remains a giant Punjabi village—teeming with glitter-bedecked grooms on white horses and resounding with the drums and trumpets of marching bands on the nights when the stars are right for weddings. And however worldly it becomes, it doesn’t become modern, or Western, or some pale imitation.

For the visitor (or expatriate), the most exciting change is the revolution in the city’s nightlife. When I was growing up, there was really no dining scene in Delhi. For ordinary folks, “home food” was the gold standard of fine cuisine, and when we did go out to eat, it was to a neighborhood snack shop like Anupam Sweets, whose deep-fried aloo tikki (spiced potato cakes), chole bhature (crisp, fried bread with black chickpea curry), and papri chaat (to hard to describe, but trust me, it’s fabulous) remain incredibly popular. Even for the rich, the only real restaurants were the dim, cavernous dining rooms inside the city’s five-star hotels.

Now, ambitious restaurateurs have raised the bar for atmosphere —if not always food—with swish lounges whose decor and ambience put them on par with the hottest spots in New York or London. Expatriates have opened top-notch Korean, Japanese, and Thai restaurants. And where once bars were grim watering holes filled with men glowering over their whiskeys, today nightclubs like the F-Bar, Bar Savanh, and Kuki are filled with gorgeous twenty- and thirtysomethings with money to burn.

Though the posh eateries and bars and the better hotels are concentrated in South Delhi, the city doesn’t really have any obvious social center like Hong Kong’s Soho or Singapore’s Clarke Quay. Instead, there are dozens of smaller hubs of activity mushrooming in various neighborhoods, known here as “colonies.”?Greater Kailash II’s M-Block Market was once known for hardware stores, Anupam Sweets, and Lyallpur’s, Delhi’s top maker of school uniforms. But since the opening of chef Ritu Dalmia’s Diva—an intimate Italian bistro with a lengthy wine list and a brief menu tailored for excellence—the neighborhood has transformed into a mini-Bohemia of coffee shops, restaurants, and bars. The same goes for Defence Colony Market. Thanks in part to the area’s popularity with expatriates, there’s hardly a building left standing that hasn’t been converted into three or four floors of cafés and lounges.

Even Connaught Place, in New Delhi’s geographic center, has undergone a much-needed revival since the opening of a Metro station about three years ago. Where once there were only?bad leather shops, second-rate clothing stores, and a few dingy bars, now there are places like Veda, the Delhi counterpart to chef Suvir Saran’s hip New York eatery Devi. On my last visit, designer Rohit Bal, the hard-partying fashionista responsible for Veda’s kitsch-glam interiors, took the place over with a bevy of gyrating male models.

But as welcome as these innovators are, it’s the amazing Indian food that makes Delhi one of the world’s great eating cities. And just as in Bangkok, the better part of eating takes place on the street or in no-nonsense, no-holds-barred chophouses and diners where overindulgence is?de rigueur —places like?Natraj Dahi Bhalle Wala Corner in Chandni Chowk, or Kake da Dhaba at Connaught Place. Some of my favorite lunch spots are short on atmosphere (and mostly without liquor licenses), but the food is unbelievable, and in many cases the other diners and the neighborhood around the restaurant are as much a “sight” as any of the monuments on the typical tourist itinerary.

Some of the best meals in town are on offer, believe it or not, in the cafeterias of the various bhavans, or representative houses, of India’s state governments. Mumbai’s restaurants can’t match Delhi’s Maharashtra Bhavan, for instance—you have to travel all the way to Pune to beat its marathi thali (a plate with an assortment of dishes). Better still is Andhra Pradesh Bhavan, where an all-you-can-eat vegetarian masterpiece costs all of US$2, and the maître d’ welcomes you to your table by shouting out the number on your receipt at the top of his lungs, as quickly as an auctioneer: “Forty-one! Forty-two! Forty-three! Forty-four!”

The bhavans, embassies, and various government efforts to promote cultural activities have also made Delhi an interesting place for shopping and a burgeoning center of Indian art. “In terms of style or fashion,” says Kumar, “in Delhi you can move, actually move, between high Bohemia and high couture. The Bohemia comes from the fact that this is the only Indian city that has a dedicated space for handicraft showrooms [on Baba Kharak Singh Marg, home to emporia from all of India’s states].

Spending a day on that street is like taking a mini-walk through India.” And we’re not talking about shops filled with tourist junk; most of the customers on Baba Kharak Singh Marg have a sophisticated eye for quality. “In other countries, you have souvenir shops and they are all a little typecast, like you can pick up a geisha doll in Japan kind of thing,” Kumar says. “This is nothing like that.”

Delhi also differs from Asia’s other so-called “shopping meccas” in that the goods on offer are distinctly local. Though malls with foreign designer merchandise are cropping up, well-heeled Delhiites still fly to Singapore or Dubai for such things, where they can be bought cheaper than in India. The items of value in Delhi are traditional handcrafted silk and cotton fabrics, hand-tooled leather, pashmina shawls, and intricate, gem-encrusted silver jewelry. But within this retail sector, too, there’s a lot going on. As Western designers have grown enamored of Indian motifs and cuts like the kurti,?Kumar is helping to lead something of a revolution in the fashion scene here. I discovered this on a recent visit to her boutique, near one of the city’s most evocative ancient monuments.

Along with several other famous names—Rohit Bal, Manish Arora, Rohit Gandhi, and Rahul Khanna, among others—Kumar has launched her innovative, Westernized, ready-to-wear label in a new shopping complex called the Crescent, near the Qutab Minar. A Modernist, semi-circular structure, the building looks less like a shopping mall than the headquarters of an advertising agency or an architecture firm, and every window gives onto a view of the great minaret. The salubrious location suits the aesthetic of the tenants, who are making Indian clothes modern without bastardizing their classic beauty. Many of these boutiques specialize in glam saris and salwar kurtas for fancy parties and weddings, but there is a lot here for stylish foreigners as well.

At Kumar’s outlet, for instance, you can find gorgeous strappy dresses. The cuts are Parisian chic, but Kumar has incorporated subtle yokes and embellishments that are distinctly Indian. Despite the economic gloom, I whipped out my wallet when I spied an irresistible ivory-colored dress with a delicate gold?booti (block print) bodice. That only whetted my appetite for a gorgeous little black dress with a boat neck and silver sequins embroidered in flower shapes—a one-of-a-kind look worth a lot more than its US$100 price tag. As Kumar assured me, “You are buying a garment with a sense of tradition in it. My line bridges the gap between the shapes and styles from Paris and the essence and ethics of the Indian subcontinent.”

As I have been thinking about why I have come to finally enjoy my hometown, Kumar’s description of the way India’s current designers have absorbed global influences without being overwhelmed by them has come back to me again and again. Delhi may be incapable of the sort of urban transformation seen in Beijing or Tokyo, but that’s because it is growing in a different direction.

Ritu Kumar’s descriptions of the kind of clothes you get here aptly describe the city’s ethos as well. “You have naughty, too. It isn’t staid just because it is traditional.”

THE DETAILS:

Delhi

Getting There

Most regional carriers operate regular nonstop services to Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport, including Singapore Airlines (singaporeair.com) and Cathay Pacific (cathaypacific.com), both with twice-daily schedules.

When To Go

Delhi’s weather is at its most pleasant from late October through March, though in the height of winter, particularly in January, be prepared for fog and average nighttime temperatures of around 8°C.

Where To Stay

Designed by an associate of Edward Lutyens in a blend of Victorian, Art Deco, and late-colonial styles, The Imperial (Janpath; 91-11/2334-1234; theimperialindia.com; doubles from US$461), which first opened in 1931, is among India’s finest hotels. Public spaces are filled with a remarkable collection of Raj-era art and furnishings, while the 233 rooms and suites offer an equally appealing mix of mod cons and old-world decor.

The Oberoi, New Delhi (Dr. Zakir Hussain Marg; 91-11/2436-3030; oberoidelhi.com; doubles from US$318) caters primarily to a business clientele, but it’s a calming oasis with some excellent restaurants and butler-serviced rooms that look out over the adjacent golf course or Humayun’s Tomb.

For a taste of urban chic à la Delhi, check into The Park (15 Parliament St.; 91-11/ 2374-3000; theparkhotels.com; doubles from US$246), where a youthful vibe is matched by some of the least expensive five-star rooms in the city. At the other end of the scale is the serene Aman New Delhi.

Originally appeared in the August/September 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Delhi Redefined”)