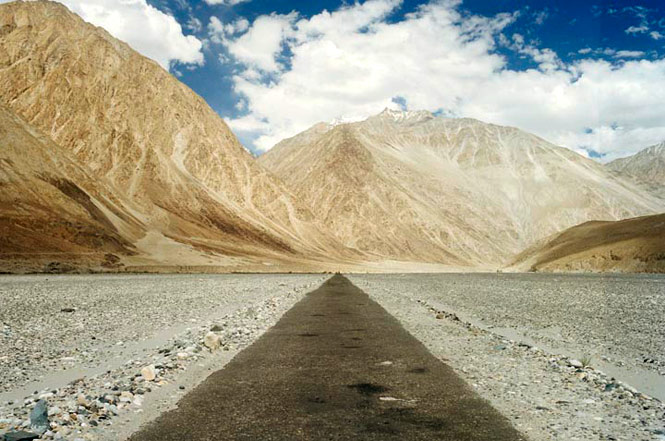

Above: The road to Nubra cuts through the arid Ladakh Range.

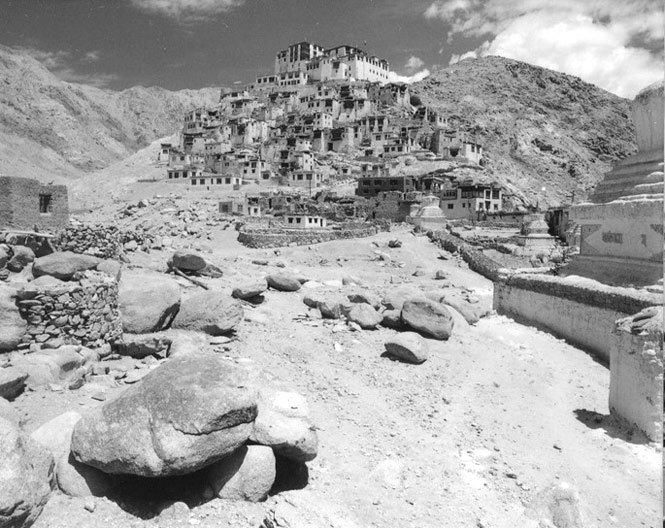

Opened to tourists more than a decade ago, northern India’s Nubra Valley remains well off the beaten track. And for lovers of sublime, empty wilderness and poetically crumbling monasteries, perhaps that’s just as well.

By Sophy Roberts

Photographs by Frédéric Lagrange

“All these borders, they’re a pain in the ass,” says my friend Jonny Bealby as we steer toward the soaring mountain pass of Khardung La. Far below us, the banks of the Indus River are beribboned with the green of early summer. I can just make out the Ladakhi capital of Leh in the hazy distance, its whitewashed gompa (fortified monasteries) shimmering in the unfiltered light.

Jonny runs a London-based travel company called Wild Frontiers, and he specializes in taking people to obscure corners of Asia—everything from Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor to Georgia’s Caucasus Mountains. And we’re heading to just such a place: the Nubra Valley, a high-altitude desert in the shadow of the western Himalayas. Raw, rugged, and remote, it’s exactly the sort of destination that Jonny thrives on. One day, he tells me, he hopes to be able to take guests through Nubra into Baltistan and on into Central Asia’s heartland. “But for now,” Jonny says, “the area’s crawling with soldiers. God, I hate borders.”

The Nubra Valley is a long day’s drive north from Leh, where I’ve spent the last few days acclimatizing and exploring the surrounding villages of the upper Indus Valley. Ladakh is a region in the politically charged state of Jammu and Kashmir; along its eastern edge runs India’s border with China, while to the west is the Line of Control, where the decades-old Kashmir dispute with Pakistan continues to play out. Ladakh itself remains peaceful, though there’s a palpable military presence. This includes the convoy that we’ve become stuck behind: a dozen army trucks packed with fresh-faced recruits from the lowlands, bound for the frontier.

That said, we have the Indian army to thank for building this road, which first opened in 1973. They also ensure that it is accessible year-round. This is a remarkable achievement in its way, for not only does a sign declare that our route traverses the world’s highest motorable pass (Khardung La, at around 5,600 meters), but in winter, the snow can pile up more than three meters deep, and wind speeds can reach 100 kilometers per hour. Yet the convoys plow through, whatever the weather. And this is the road they all take, as it’s the only overland supply route to the Siachen Glacier, a vast tongue of ice beyond the far end of the Nubra Valley where thousands of Indian soldiers are currently deployed. Although Siachen (meaning, ironically, “the Place of Roses”) has been a flashpoint with Pakistan since 1984, an uneasy truce has held for the last seven years. I can’t imagine a bleaker place to be stuck in a stalemate.

Nubra, once off-limits, welcomed its first tourists in 1994, though visitors need a special permit to enter the area. That proved easy enough to acquire, but I’m still grateful for Jonny’s expertise on this trip. When I e-mailed him about my plans to visit Nubra, he not only put together a driver, a guide, and an on-the-ground fixer, but he also volunteered to join me. He happened to be in the region anyway, building a pool at his house in Pakistan’s Hindu Kush. Still, I can tell that he’s thrilled to be along for the ride.

“Nubra is one of the most exciting, remote parts of the Himalayas,” he says as our four-wheel-drive snakes its way upward. “It encapsulates the intrigue of the old Silk Road trade routes that used to crisscross the region, linking the Indian subcontinent to Kashgar. I just find it fascinating up here.”

The road is growing steeper. Leh has disappeared from sight and the crest looming before us—the high pass at Khardung La, blasted open by explosives four decades ago—appears jagged and foreboding. Behind me, I can see the icy white peaks of the Zanskar Range, which divide Ladakh from the rest of India and puncture the monsoon clouds before they have a chance to reach these wild northern valleys. Both the upper Indus and Nubra valleys sit in one of the world’s most dramatic rain shadows.

The more we climb, the more barren the landscape becomes. The road is littered with loose stone. But with Jonny’s indomitable spirit —and a good car—for company, I’m feeling exhilarated. Until, that is, we finally reach Khardung La and I look down on the road we’ll follow into Nubra itself. The altitude is taking its toll. My breathing is shallow. I have the beginnings of a headache. It’s June, the warmest time of the year—and thus the safest for travel—but I can see debris trails from avalanches curling through a snowfield to my right. The pass itself splices a glacier, which is constantly spitting grit onto the narrow, unevenly paved road. There’s no grass, no greenery, only bare, buff-gray rock. Streams of water from the melting snow have washed away parts of the asphalt.