A soupy fog is closing in, and the sharpness of the air bites at my lungs. The army trucks we’ve been following have caught up with another convoy, and now our driver, Sonam, is engaged in a terrifying series of leapfrogging maneuvers to pass them on what is essentially a single-lane highway. Ominously, I spot a sign memorializing 13 Madras Sappers who lost their lives on this precipitous stretch. Then I notice a graveyard of mangled jeeps and cars lying hundreds of meters below a switchback. Some are burned out, others crumpled into scrap metal. It could be decades’ worth of debris—given the terrain, you’d never be able to pull the wreckage out, even if you wanted to.

Jonny takes it in his stride when we swerve to avoid a marmot. I’m not quite so calm, particularly with a sheer drop yawning right outside my window. At least, I tell myself, we’re traveling in relative comfort, which is more than I can say for the American explorers Fanny and William Workman, who, in 1900, negotiated this pass by yak. “As the rider sits upon its broad back, and looks down on the massive shoulders and curling horns, he may easily imagine himself seated astride a huge horned beetle,” Fanny wrote of her lumbering conveyance. And I’m also better off than the people in the tiny Maruti Suzuki that we’re now trailing. The car is packed with four Sikh businessmen from Chandigarh; they have some sort of contract with the army base at Siachen, and their boxes of wares are strapped to the roof. When they get stuck in a washout, we stop to give them a hand. “I wanted to see if it was possible in this car,” says the turbaned driver, patting the Maruti’s hood. “I guess next time, we’ll take the bus.”

Were it not for the army’s presence, this would have to be among the most desolate places on the planet—an arid wilderness where nothing much grows unless it’s within a few meters of a river. Of which there are two: the Shyok and the Nubra, both fed by the meltwater of the Siachen ice field, the world’s largest non-polar glacier. Along their irrigated banks are fields of wheat, barley, peas, even a few almond trees. Yet there are hardly any villages. I see plenty of yaks, but little else in the way of livestock—some goats, some chickens—and very few wild animals, apart from the aforementioned marmot. Jonny tells me that ibex and chiru (Tibetan antelope) inhabit the surrounding mountains, but that they rarely venture into the valley.

Descending from the pass, we enter Khardung village, one of Nubra’s few sizable communities. It comprises maybe 100 houses, their stone walls honey-hued in the slanting light of the afternoon. Needing to stretch our legs, we stop outside a shop that sells little more than chocolate biscuits, soap, and baskets of fruit. Nearby, a group of soldiers have struck up a makeshift game of cricket, using an old soda bottle as a wicket. It seems to be a place carved out of nothing, save perhaps for the orange and cream sunshades that color the roadsides. Jonny tells me that they’re made from parachute nylon, pilfered by enterprising locals from the foot of the Siachen Glacier, where army supplies were airdropped through the winter.

Later that evening, after 10 hours on the road, we finally pull up at our home for the next few days—a family-run encampment of 30 tents in the heart of the Nubra Valley. The place is called Tirith Camp, and is one of four such operations in the area catering to the valley’s burgeoning tourism industry. A stream runs through it, flanked by an orchard of apples and apricots. There’s also an organic garden.

Dinner, prepared by the owners, is spectacular—spicy Ladakhi vegetable dishes concocted on an iron stove, the kitchen thick with cooking smells and the sound of wood pounding on wood as yak milk is churned into butter. When the family first began taking in guests, accommodation consisted of four rooms in their 200-year-old farmhouse, a two-floor, stucco-and-wood design typical to Ladakh and neighboring Tibet. Business has apparently been good. They added the tents—surprisingly comfortable affairs with wooden beds, crisp sheets, and concrete floors covered in hand-knotted rugs—a few years back, and tonight, they’re running at full capacity, mostly with domestic tourists.

It’s only when I wake up the next day and take in the wide vista, that I fully appreciate the appeal of this silent and untamed valley. I love the wilderness; I can travel for days in places like Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, and China’s Taklamakan Desert. But Nubra seems somehow even more compelling.

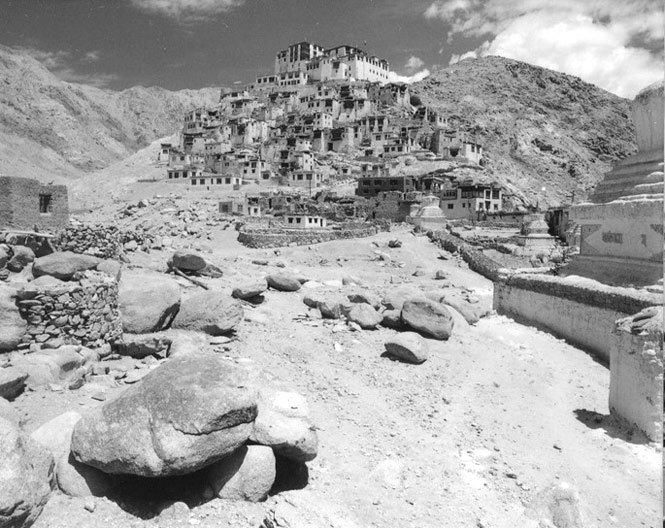

At first, I’m drawn in by the expanse of featureless plain, punctuated by lonely white burial stupas on the sandy floor of Nubra’s ancient glacial bed. Then I start to spend some time in the monasteries perched on the valley’s slopes, and decide that, for me at least, the place resonates more deeply than other parts of the Himalayas. For in Nubra, the monasteries haven’t been tarted up for tourists as they have been in towns like Thiksey or Hemis, which are the grand Buddhist highlights of any visit to Ladakh’s Indus Valley. Here, the buildings are raw and crumbling and falling in on themselves; shafts of light pierce broken roof tiles, illuminating ancient thangkas or transforming a common brass prayer wheel into gleaming gold. Yet the halls are packed with novice monks, who run around barefoot or in ill-fitting flip-flops. It’s entrancing.

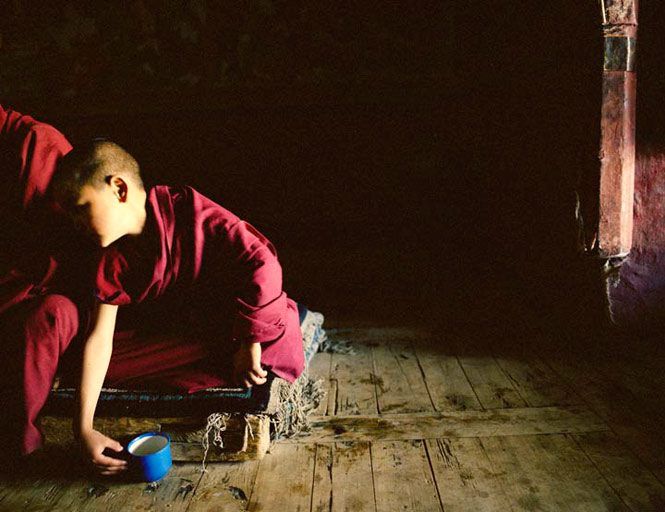

Indeed, Nubra is so rich in atmosphere that it grips the imagination. One morning I visit the cloisters of Samstaling, situated above Sumur village. Like the other monasteries I visit, Samstaling belongs to the Yellow Hat sect, the predominant school of Tibetan Buddhism. In its prayer hall, I watch as novices dutifully fill metal cups with chai from steel kettles, before delivering them to their elders. One of the older monks castigates a youngster for forgetting to prostrate himself, but his eyes are kind, laughing. Outside in the main courtyard, amid vast vats of steaming rice, are gathered lay children, 40 or 50 of them, who have come here for schooling. I talk with a 70-year-old who has been a monk at Samsatling for 60 years; he was born in Nubra, and has never left. He proudly tells me how the valley’s monastic communities are getting bigger all the time; how in Nubra, children can study both English and Hindi, and that the standards of education among the valley’s mostly Buddhist population are as good as any in Ladakh. I also meet a seven-year-old whose journey is just beginning; his family delivered him to the monastery only a few days earlier. His eyes are big and round, his head freshly shorn. I can’t tell whether the tremors of emotion that play across his face are of fear or excitement. Likely they’re a mixture of both.

I visit Disket, too, which is Nubra’s largest monastery, perched precariously on a mountain spur much like the famous Tiger’s Nest in Bhutan. And yet, the place that moves me the most is one we almost drive right past: the ruins of an ancient hermitage near Sumur. I wander through its deserted, rubble-strewn courtyards, ducking under low wooden lintels, peering into the remains of mud-brick chambers. The only life I see is a pair of birds pecking in the ashes of a soot-stained hearth. Anywhere else, this would be a UNESCO-protected heritage site. But not here, not in Nubra, not in a place where the silence is broken by the rattle of army trucks rolling stubbornly up the valley to supply an intractable, impossible conflict.

Just another 45 kilometers north along the Nubra River, civilians can travel no farther. The last accessible village is Panamik, which, in the golden age of the Silk Road, was a busy way station—the last major settlement before the caravans plunged into the mountains of the Karakoram on their way to Kashgar. Here, they’d halt to make final preparations for two weeks of hard travel, during which there would be no supplies, not even grazing for their animals.

It’s difficult picturing that scene today. At least, it is until I encounter a herd of Bactrian camels in the sand dunes of Hundar. Jonny says that there are about 100 of these shaggy, double-humped beasts in Nubra; they’re not indigenous, but rather are descended from camels left behind by the caravans. They’re sometimes used to carry fertilizer to otherwise inaccessible fields. Mostly, however, they’re used to cart tourists on hour-long trips through the valley, or to pose for photo opportunities. I’m enthralled, as much by the camels as by one of their handlers, a green-eyed man called Mohammed. He tells me that his great-great grandfather was a Briton—a Mr. Johnson. I immediately think of Kipling, of the Great Game, of the race to Turkestan and the colonial powers that intrigued over the routes through Central Asia.

And I think of Jonny Bealby’s vision—to one day take people from Nubra into Pakistan and thence to China. Because he’s right about one thing: in this sublime wilderness, there’s tremendous appeal for travelers. I’ve been here only briefly, and I want to keep going, to follow the old caravan trail into the mountains. But even with Jonny along, it isn’t going to happen. Borders, as he so succinctly puts it, are indeed a pain in the ass.

When to Go

The Ladakh region enjoys its most pleasant weather during the warmer months of June to September.

Getting There

Both Indian Airlines (indian-airlines.nic.in) and Jet Airways (jetairways.com) offer direct connections to Leh from New Delhi, 600 kilometers to the south. Permits for entering Nubra can be obtained through any travel agency in Leh within 24 hours.

Touring Nubra

Wild Frontiers (44-20/7736-3968; wildfrontiers.co.uk) runs a number of small-group tours to the Indus, Nubra, and Kashmir valleys during the summer months. This includes a 15-day Leh–Srinagar itinerary from June 20 to July 6, 2010, priced at about US$3,000, full board, including ground transportation. The company can also organize tailor-made itineraries to the region.

Originally appeared in the April/May 2010 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“The High Road”)