Above: Overlooking Ashgabat’s Presidential Palace.

The Central Asian republic of Turkmenistan is slowly opening up after years of political and economic isolation. It may not be your typical holiday destination, but for a glimpse of the country’s ancient ruins and more surreal attractions (flaming gas pit, anyone?), there has never been a better time to visit

By Mark Godfrey

Photographs By Andrew Rowat

Until 2006, lots of things were banned in Turkmenistan. At the decree of President Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov—or “Turkmenbashi the Great, Father of all Turkmen” as he preferred to be known—there was no opera, no ballet, no video games, no car radios. Circuses were prohibited, as was (no argument here) karaoke. When it came to personal appearance, gold teeth were frowned upon, newscasters were not allowed to wear makeup, and young men were forbidden to grow beards or long hair.

I first visited the country of five million people in 2006, just before the sudden demise of Niyazov, Turkmenistan’s Moscow-appointed leader of 21 years. At the time, the international media was intent on comparing the former Soviet state to North Korea; President-for-Life Niyazov was the next Kim Il-sung, they claimed. On subsequent trips, I’ve learned that while there are undeniable similarities between the two countries, including intolerable waste and bureaucracy, Turkmenistan is no Hermit Kingdom. If anything, it’s one of the most stable and optimistic nations in Central Asia, intent on putting the eccentricities of the Niyazov years behind it and opening, slowly, to the world.

A land of vast deserts wedged between Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and the Caspian Sea, Turkmenistan has been shaped by the comings and goings of many traders, and armies, over the centuries. Alexander the Great came and conquered, ancient Persian and Arab empires followed. Later, Mongol invaders laid the country’s Silk Road cities to waste. Occupation by imperial Russia in the 19th century and Soviet rule in the 20th eventually turned the nomadic Turkmen into city dwellers, factory workers, cotton farmers, and—in the 1960s, with the discovery of natural gas—riggers and drillers. After the USSR began to disintegrate in 1989, Niyazov focused his attention on getting gas out of the ground and turning his Russified country Turkmen again. He abandoned Cyrillic for a Latin-based script, and designed a green-and-red flag that would reflect the twin pillars of national identity: Islam and carpet weaving. Keen to protect traditional Turkmen values, he banned pretty much anything he deemed a negative foreign influence. Then he went on a building spree.

In the three years since the dictator died, officials have been trying to figure out what, exactly, Niyazov did with all the country’s money. Much of it was clearly spent on self-promotion. Aside from countless portraits of the megalomaniacal leader, there are an estimated 10,000 Niyazov statues in Turkmenistan. He’s also pictured on the country’s banknotes, on vodka bottles, and packets of tea. He developed an eponymous scent, christened a town and even a meteorite in his own honor, and decided to rename the months of the calendar—January after himself, April after his mother.

Niyazov’s successor, former health minister and deputy premier Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, is a Soviet-style autocrat cut from the same cloth—heck, he even looks like Niyazov. But Berdimuhamedow also recognizes the need for reform: he is working to modernize the economy, encourage tourism, improve pensions, and revamp the country’s education system. And yes, he’s reverted to the old calendar. Change is coming, gradually.

Indeed, not much happens in a hurry here. It’s the middle of summer and scorching hot when I return to Turkmenistan in 2008. I walk over the country’s northern border from Uzbekistan to be greeted by Angela, my swaggering, government-appointed guide from the state-owned travel company. When I cross, she’s sitting in a windowless tin cabin with the brawny customs guards, enjoying a cigarette and a mug of sweet tea. We spend the next hour doing more of the same—to appease the guards, Angela tells me later—before I’m ushered into a rattletrap, USSR army surplus Niva van en route to Ashgabat, the country’s capital, on the opposite side of the country.

We stop briefly in Konya-Urgench, a nondescript market town near the border, to change money and stock up on food and water. Despite the midday heat, elderly folk wander the dusty streets in woolen telpek hats and long dark coats. Nearby, teenagers browse cheap Chinese clothes while housewives bargain for rough blocks of soap and sugar, the only products in the market that appear to be made locally. Turkmenistan wasn’t ready for life outside the embrace of the planned economy, it seems. Most of its industry, fed on subsidies from Moscow, collapsed in the early 1990s, forcing locals to eke out a living in small, home-based industries.

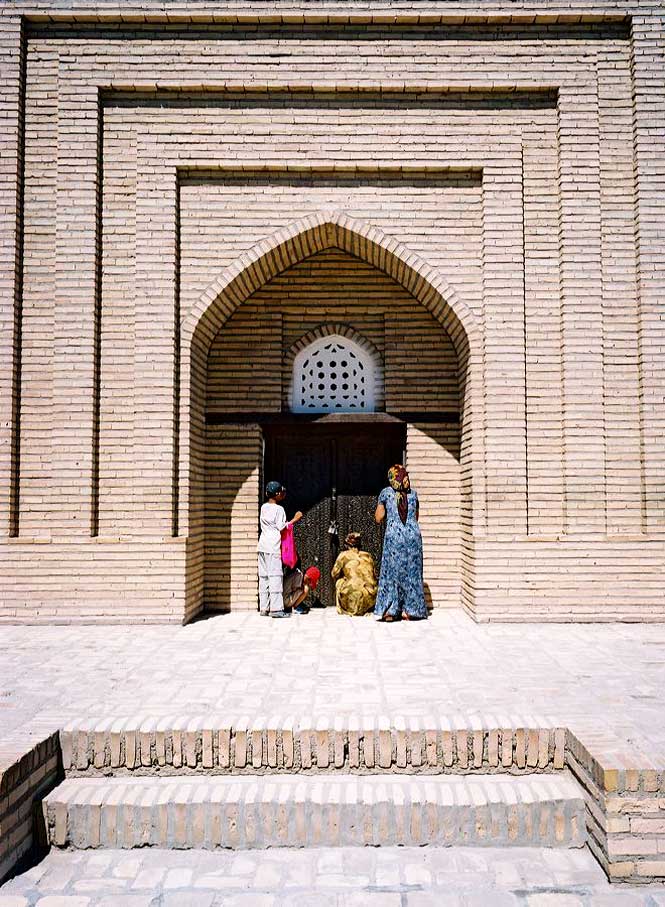

On the outskirts of town are the unexcavated ruins of the 12th-century capital of the Khwarezm satrapy. The complex of forts and tombs is all that remains of the Silk Road city, which once outshone all but Bukhara before being sacked by Genghis Khan in 1221. What remains today is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but the ruins draw few visitors. The handful of locals we do pass are huddled under umbrellas to escape the baking afternoon sun and seem more interested in us than in the early Persian architecture that surrounds. At the center of it all is the golden-bricked Gutluk-Temir Minaret, shadowing the domed mausoleum of Il-Arslan, the shah of Khwarezm from 1156 until his death in 1172. More impressive is the beautiful Soltan Tekes Mausoleum. Here, small banknotes are stuck under pebbles by the door, decorated with the scribbled wishes of young women hoping for marriage and children.

For the next three hours, we drive along lonely roads where kids in plastic sandals sell watermelons and cups of sweet coffee to passing motorists. There are frequent checkpoints. Each time we halt, Angela good-naturedly presents our documents and offers the guards a cigarette. Most people lucky enough to drive, Angela tells me, are forced to hand over the equivalent of US$1 every time they are stopped—it’s the price you pay for owning a Lada in a country were many still get around by donkey and cart. This kind of “bureaucracy” makes independent travel in Turkmenistan a challenge, and unless you’re on a transit visa, the only way to see the country is the government’s way. Still, that’s not entirely a bad thing: Angela speaks fluent English and has a good grasp of the sites we visit. And our driver is a decent cook, as we soon to discover.

By dusk, we reach our destination: the hamlet of Darvaza, around 260 kilometers from Ashgabat in the middle of the Karakum Desert, and home to Turkmenistan’s unlikely cult attraction, the “Door to Hell.” While drilling in the area in 1971, geologists hit an underground cavern of natural gas. The ground collapsed, leaving a crater the size of a football field. To avoid the buildup of poisonous fumes, the government decided to let the gases burn. They have been burning ever since. In the glow of the blaze, our driver, a muscular ex-military type, prepares a Turkmen feast of vodka and roasted goat, taking great pride in cooking and carving the animal before us. While we’re eating, two groups of locals pull up in massive, yellow John Deere shovel loaders: the wheels alone are two meters tall and come to a stop dangerously close to the edge of the gas pit. The sounds of Russian and Turkish pop music and chatter fill the night. The partygoers finally depart in the early hours of the morning, leaving us to roll out our sleeping bags in the sandy dunes, and fall asleep under the stars.

We’re on the road by 5 a.m. to escape the heat, and are ensconced in our Ashgabat hotel, showered and sand-free, by noon. Aside from a cluster of five-star lodgings downtown, Ashgabat’s Berzengi district is the main port of call for foreigners spending the night in the capital. At our hotel—one of a dozen or so custom built to house visiting “aliens”—we share the dining room with serious-looking engineers from a Chinese petroleum company. They tell us they’re on a stopover to buy gas for Beijing.

Later, on a leisurely jog around the city, I barely meet a soul. Ashgabat is immaculate, largely because it’s empty. To build his utopia, Niyazov moved much of the population to outlying villages, requisitioning their houses for building projects. Some 700,000 people inhabit Ashgabat today, though nobody appears to live in the bizarre Beverly Hills–meets-Kiev apartment blocks that Niyazov (a town planner by training) constructed around town. Their main function today appears to be as a backdrop for photos. Tourists and wedding parties pose in front of the gaudy buildings, as well as under the stern gaze of the city’s many gold-plated Niyazov statues, the most surreal of which—a gilded figure of the former leader that rotates to face the sun—stands atop the 75-meter- tall Arch of Neutrality in downtown Ashgabat.

Fans of modern architecture might also appreciate the Olympic Stadium (which has no connection with the Olympic Games) and the World Trade Complex (notable for its conspicuous absence of trade). But by far the city’s most interesting building is the Tolkuchka Market, a melting pot of colors and sounds that reverberate through Dickensian warrens lined with sand. Swarthy women wander the aisles dressed in identical ankle-length cotton dresses, each fashioned with a long U-shape of traditional embroidery down the front. Despite Niyazov’s edicts, the younger women here parade between stalls in skin-tight jeans, talking on the latest-model Nokia phones. We stop at the stall of a cutler, who is sitting on his coat between pink pillows and giant bags of spongy caramel. He takes a break from selling knives and whips out a traditional lute-like instrument, his wispy white beard almost tangling in the strings while he plays a sad, twangy tune. Like most men here, he wears a bright takya skullcap embroidered with floral patterns.

Above, from left: Independence Park in Ashgabat; Rush hour in the port city of Turkmenbashi; A rotating statue of Niyazov crowns the Arch of Neutrality.

I absentmindedly show some interest in a handwoven rug hanging in the sun at an adjacent stall, and before I know it I’m swamped by dozens of wrinkled stall-keepers pulling carpets from their walls and floors for me to look at. I settle on two saddlebags for US$30 a piece, both beautifully woven from sheep’s wool and decorated with tribal motifs. The sellers shake out kernels of corn and twigs as evidence of the bags’ authenticity. They’d been used the day before on pack mules in a nearby village, Angela translates.

We also stop at Ashgabat’s main bookstore, where, in 2006, I had bought a copy of Niyazov’s Rukhnama (“The Book of the Soul”)—a thick tome of homey wisdom penned by the former leader to provide “spiritual guidance to the nation.” When it was first released in 2001, bookstores and mosques alike were ordered to display the volume with pride. Needless to say, the country’s imams were less than happy about having the pink-and-green book propped up next to the Koran, and were quick to see it banished after Niyazov’s demise. In the bookshop, smiling sales clerks still wear traditional dress, their black hair tied in neat plaits. But the Rukhnama has disappeared from the shelves here as well. All that’s left now are piles of government propaganda.

The next day we visit the 15TH-century shrine of Seyit Jamal ad-Din. Less than an hour’s drive east of the city, this is a popular destination for Ashgabat day-trippers. Much of the tomb was reduced to rubble by a devastating earthquake in 1948 that left more than 100,000 dead (including most of Niyazov’s family). But a recent grant from the U.S. Embassy saw the site partly excavated to create a platform for worshippers. On the surrounding gravel, extended families picnic on tomato- and-onion salad and corek flatbread.

Some 370 kilometers east of the capital, another of Turkmenistan’s UNESCO-listed sites, Merv, is in an equal state of disrepair; you need to use your imagination to appreciate its glories. Our government-appointed guide around the site is David, a student from nearby Mary, the country’s fourth-largest city, who picked up most of his English from watching satellite TV. An oasis on the Murghab River in the Karakum, Merv was founded in 559 as a garrison town by the Persian king Cyrus. Over the centuries, a palimpsest of settlement was built up by subsequent conquerors: Greeks, Arabs, Mongols, and Uzbeks. The Seljuks, another Turkic group, took over in the 11th century, building libraries and madrassas and planting the orchards where Omar Khayyam later wrote some of his best poems and treatises. By the 12th century, Merv was thought to be the largest city on earth. Its heyday proved short-lived. In 1221, Mongol warriors swept across the region from their base in eastern Asia, invading dozens of Silk Road cities including Urgench and then Merv. Neither city recovered.

David leads us through the ruins, pointing out occasional shards of bone and pottery bearing testament to the site’s rich history. Merv remains a mecca for archaeologists who come to its wide, open spaces for the opportunity to explore some of the world’s greatest civilizations in one spot. David tells us that it’s not uncommon for diggers to uncover chalices, jewelry, and weaponry, all of which are handed over for display in the National Museum in Ashgabat. On the day we visit, a handful of preservationists from Tehran are at work in an outer field, carefully reshaping the walls of a crumbling madrassa.

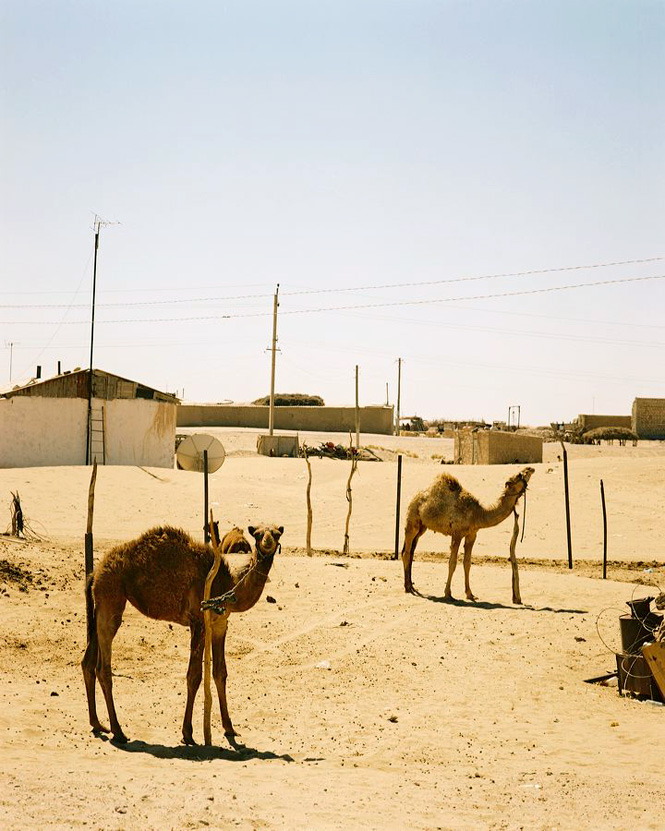

After dodging packs of cheeky single-humped camels on the drive to Turkmenabat, near the Uzbek border, we stop for lunch at a small roadside restaurant. There are smoky lamb kebabs, a heaped platter of salad, and Russian Baltika beer and vodka. Later, waiting for my Turkmen Airlines flight back to Ashgabat, I’m impressed by the modernity of the airport’s departure hall, which, aside from a mural of cosmonauts, bears none of the insignia of the country’s Soviet years. I browse the stalls selling vodka, carpets, and dates, looking for an appropriate souvenir to take home. And then I find it: a dusty bottle of Niyazov’s famed scent—the very essence of a nation.

THE DETAILS:

Turkmenistan

Getting There

National carrier Turkmenistan Airlines (turkmenistanairlines.com) operates limited flights between Bangkok and Ashgabat, while China Southern Airlines (cs-air.com) flies from Guangzhou to Ashgabat via Urumqi on Tuesdays and Saturdays.

It’s recommended that you book your flights through a local travel agent, who will also be able to organize a letter of invitation (essential for a tourist visa) as well as guides and lodgings. Be warned: visas can take several weeks to process.Try Stantours (stantours.com) or Ayan Travel (ayan-travel.com).

When To Go

It’s best to visit in spring or autumn, as summer can be brutally hot, and winter brutally cold. In April, you’ll catch the highly entertaining horse races at Ashgabat’s hippodrome.

Where To Stay

In central Ashgabat, the European-style Grand Turkmen Hotel (7 Gorogly Ulitsa; 993-12/512-050; doubles from US$175) is one of the nicest places in town. The best hotel in Mary, near the ancient ruins of Merv, is The Margush (Gowshuthan Kochesi; doubles from US$90).

What To Do

For a comprehensive introduction to Turkmen carpet weaving, visit the Carpet Museum (5 Gorogly; closed Sundays) in Ashgabat. Don’t miss out on riding an Akhal Teke, one of the rarest and most prized horse breeds in the world and native to Turkmenistan. Guides can arrange horse treks with local stables. For bizarre tributes to the country’s past rulers, visit Ashgabat’s massive Azadi Mosque, built in a similar style to the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, but using marble and gold.

Originally appeared in the May 2009 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Turkmen Tales”)