Naturalists at Langkawi’s high-end hotels are leading the charge to protect native flora and fauna as the Malaysian resort island faces a tourism boom.

It’s early in the morning on the Kilim River, a snake of turbid green water flanked by craggy limestone outcrops and the blackened trunks of mangrove trees. A brahminy kite—known locally as an eagle—circles above our boat, its snow-white belly gliding against a dusty blue sky. At the bow is Aidi Abdullah, the cheery chief naturalist at the Four Seasons Resort Langkawi, explaining, with much gusto, the life and times of a mangrove tree.

Environmentalist Irshad Mobarak at The Datai Langkawi. All photos by Leisa Tyler.

The only tree capable of living between the land and the ocean, mangroves don’t just provide shelter for juvenile fish and crustaceans; they turn salt water to fresh via a membrane in their leaves. But that’s nothing compared to the spindly, half-submerged roots. Binding with their next-door neighbor, mangroves share both foundations and nutrient sources—all in perfectly equal measures. “It’s a true socialist tree,” says Abdullah. “The collective is stronger than the individual; there is no ruling class.”

Kayaking amid mangroves on the Kilim River

These mangroves, some of the world’s biggest, are an enduring draw on Langkawi—a cluster of 104 islands formed more than half a billion years ago, long before the Himalayas even came into being. The bald peak of Gunung Mat Cincang, which rears up behind idyllic Datai Bay on the main isle’s northwest corner, was the first part of Southeast Asia to rise from the seabed during the Cambrian period. Langkawi’s rare rock formations boast a complete Palaeozoic geological range, from Cambrian to Permian.

Aidi Abdullah, chief naturalist at the Four Seasons Resort Langkawi

It’s a unique trait that, in 2007, earned the archipelago a prestigious UNESCO Geopark listing. Then things started to get a little shaky. Though large parts of Langkawi are protected, like Kilim Karst Geoforest Park, burgeoning tourism numbers and related developments have strained resources and the ability to monitor activities within the parks. Strong wakes from speeding tour boats have triggered erosion, destabilizing trees along the Kilim’s banks, while operators feed wild brahminy kites with skins from battery-farmed chickens containing antibiotics and growth hormones—one factor that has led to weakened egg shells and a subsequent drop in kite numbers. In 2014, UNESCO declared that the island fell short of what it considered a responsible duty of care, and if issues such as eagle feeding and speeding boats weren’t rectified by June 2015, Langkawi would lose its geopark status.

In response, the Langkawi Development Authority (LADA) filed reports to address some of the more dubious activities and scraped through the assessment. “The problem in Langkawi is the lack of enforcement. LADA is only consultative. They cannot apply the rule of law,” says Abdullah, who sits on LADA’s Consultative Council for Conservation and is also a geopark ambassador.

Through it all, Abdullah has been instrumental in lowering boat speeds and reducing carbon emissions and oil spills by convincing boat owners to switch from two-to four-stroke engines. He’s also helped discourage both eagle feeding and the use of mist nets that trap migratory birds, while leading rubbish collection and mangrove planting teams in Kilim each year, with more than 5,000 trees planted since 2010.

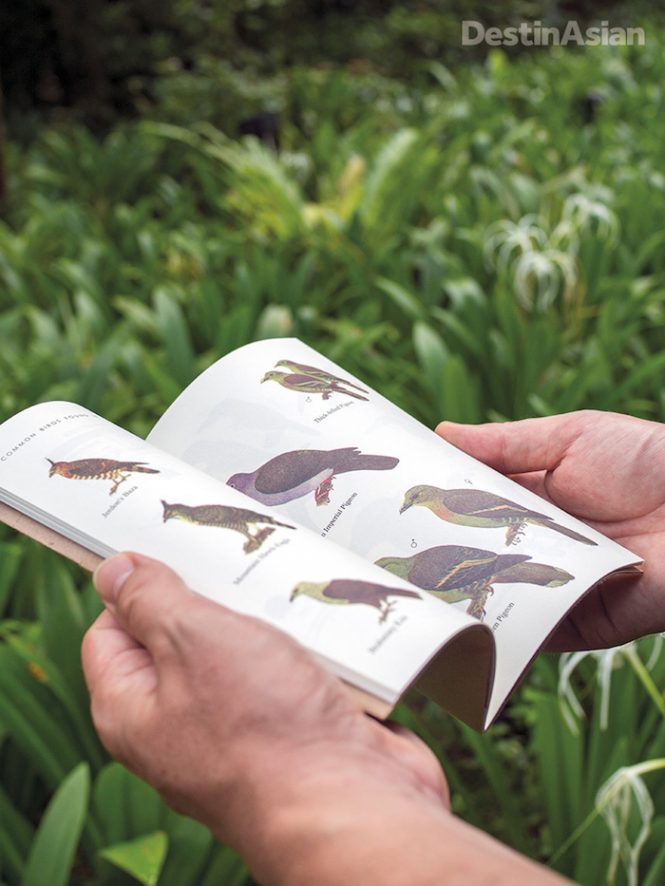

Identifying birdlife from The Datai’s nature compendium

Plagued with lax development regulations and even poorer enforcement, Langkawi remains a battlefield for environmental warriors. Last year, Irshad Mobarak—The Datai resort’s resident naturalist and owner of an eco-tour company, Junglewalla—locked horns with a development company that had cleared a large swath of the Kilim mangrove forest for a hotel. How they managed to obtain initial approvals is unclear, but the project has since been suspended. His battles against illegal logging and land clearing follow a similar pattern.

A former investment banker, Mobarak has spent over a decade mediating between local groups and government, urging tourism operators to adopt a more sustainable approach. While he says LADA has become more proactive, the results have been disappointing. Mobarak believes the key is raising awareness among visitors, so they know how to behave in an ecologically sensitive area like the Kilim. “Tourists need to understand that when they buy an eagle- or monkey-feeding tour, they are contributing to the issues associated with them. If they choose to only patronize operators with good practices, then Langkawi’s problems are less.” As an eco-tourism provider, Mobarak is also setting an example with the recent launch of a commercial solar-powered boat—a first for the island and Malaysia as a whole.

Over at The Datai, he’s been replacing non-native plants with local species to help provide food and habitat for birds, butterflies, and mammals—including the families of wild boar and monkeys already living on the grounds. The 23-year-old resort will close in September to undergo extensive renovations; Mobarak is advising on water conservation, plastic-free water bottles, and wildlife management for the revamp.

Nearby, retired American marine biologist Dr. Gerry Goeden has spent the last six years regenerating the reef in front of The Andaman, a Luxury Collection resort—the only other hotel flanking Datai Bay. Years of fishing activity coupled with the effects of gray water from the hotels had weakened and bleached the coral before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami swept most of it away. “It was in terrible shape,” Goeden recalls. Alongside an ongoing initiative to clear the reef of dead coral, The Andaman has built a dedicated nursery where guests can snorkel among the corals and tropical fish. “We had a liability that we could turn into an asset,” Goeden says. “Our initial goal was conservation—to revitalize the reef. Now it is about education and getting guests involved.”

Where to Stay

Family-friendly The Andaman, a Luxury Collection Resort, Langkawi (60-4/959-1088; doubles from US$191) has 178 rooms and Jaya, A feet-in-the-sand restaurant serving locally caught fish. Next door, The Datai Langkawi (60-4/950-0500; villas from US$524) offers a range of nature experiences, including beach and butterfly walks. The resort will close for renovations from September 2017 to March 2018. Four Seasons Langkawi (60-4/950-8888; doubles from US$650) is flanked by a kilometer of white-sand beach and karst outcrops. The Malay restaurant, Ikan Ikan, is highly recommended.

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2017 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Changing Course”).