The world’s fourth-largest island is packed with wonders, and nowhere more so than on its less populated west coast, a region of otherworldly wildlife and bewitching landscapes.

From my vantage point in a small field beside the Avenue of the Baobabs, Madagascar’s iconic trees appear almost cartoonish in the late-afternoon sun, with bulbous trunks and crowns of root-like branches that look like they were drawn by Dr. Seuss. Children race up and down the packed-dirt road that cuts through the grove, laughing as they kick up plumes of red dust in their wake. I share their glee. But mostly what I feel is a sense of wonder. Ten years, after all, is a long time to wait to see a tree.

I first learned about these baobabs a decade ago while watching an episode of BBC’s Planet Earth. I was transfixed. The world’s largest succulents, baobabs can be found in mainland Africa and Australia, but most species are endemic to Madagascar, whose flora and fauna have evolved in almost uninterrupted isolation since the island broke away from what became the Indian subcontinent 85 million years ago. More than 100 species of lemur are among the indigenous fauna, as are the panther chameleon, the tomato frog, the catlike fossa, the elusive nocturnal aye-aye, and the marvelously named satanic leaf-tailed gecko. And that’s just the tip of the island’s biological iceberg—more than 600 new species have been discovered here since the turn of the millennium, mostly plants but also fish, amphibians, insects, reptiles, and mammals.

And then there are the trees at the Avenue of the Baobabs. These are Adansonia grandidieri, or giant baobabs, the largest of them all, rising as tall as 30 meters above the ground. After 10 years of imagining what it would be like to actually lay eyes on them, they do not disappoint. Nor does my guide Herilala fail to mark the occasion with a story.

“Every Malagasy child learns the legend of the baobab,” he says. “When the world was young and covered by forest there were many big trees, and one of these trees was the mighty baobab. The baobab trees were very proud of their size, and in their pride they tried to challenge God. God was not happy with their arrogance, and as a punishment he decided to pull them up from the ground, turn them upside down, and plant their heads back in the earth. That is why we call them the Roots of the Sky.”

I’ll never look at them the same way again.

A New York–based photographer, I have come to Madagascar to capture images of its wild west coast with luxury trip planner Cox & Kings, The Americas. My first day is spent acclimatizing in Antananarivo, the capital. Situated amid agricultural plains on the island’s central plateau, Tana (as the locals call it) is a sprawling tapestry of red-brick buildings, pastel-hued stucco homes, rust-stained tin roofs, and some crumbling piles built during the French colonial period (1896 to 1960). Without much in the way of monuments or museums, there’s little to hold the visitor for long, though Tana still manages to exert a certain appeal. Perhaps that’s because it is unlike any other city I’ve visited. At the peak of every hill—and there are many of them in Tana—a church steeple pokes out above its neighbors. Down below, traffic-clogged streets present a motley parade of oxcarts, pedicabs, old Renaults and Citroëns, and taxi-brousse minibuses. There are fancy French restaurants in the better part of town, and baguettes sold by the roadside everywhere else. And should you tire of the urban sprawl, glimmering rice paddies right on the city’s perimeter provide oases of green, complete with straw-hatted farmers and families of fluffy ducks.

The next morning, an hour-long flight on an aging Air Madagascar turboprop brings me to Morondava, a mellow seaside town overlooking the Mozambique Channel. Herilala meets me on the tarmac. Dressed in a dusky gray T-shirt and tan cargo shorts, my guide for the week rolls out a greeting with an orator’s aplomb.

“Inona vaovao, Matthew. Welcome to Morondava, the gateway to the west.”

Surrounded by bucolic fishing villages and straddling a river delta of the same name, Morondava also has a fine beach area, Nosy Kely, where a number of small hotels and breezy restaurants are located. After dropping my bags in a bungalow at Palissandre Côte Ouest, I jump back in the waiting Nissan SUV with Herilala and our driver Faly for the 30-minute drive to the Avenue of the Baobabs. But first we stop at the market that lines Morondava’s only paved road. Shaded by a canopy of crisscrossing tarps, it’s a cacophonous labyrinth of stalls where young men armed with cleavers hack away at all manner of meats on cement countertops, and mud-enveloped mangrove crabs slowly inch their way out of baskets onto the concrete floor, only to be swooped up and returned by watchful women in bright, patterned skirts. Outside, zebu-drawn carts unload impossibly plump and juicy mangos.

Fascinating as all this is, it’s nothing compared to my long-awaited arrival at the Avenue of the Baobabs. Herilala’s “roots of the sky” are mesmerizing, monolithic. There are about half a dozen trees in the group, and they are said to be as old as 800 years. Once, these baobabs would have been encompassed by thick forest, but the surrounding land has since been cleared for agriculture, leaving them standing alone like the pillars of some ancient temple. We stay until the setting sun washes their trunks in a golden light.

“Look—kintana,” says Herilala with a motion to the night sky above, where a blanket of stars has unfurled. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen so many.

Back at the Palissandre Côte Ouest, I tread across the sand to my waiting bungalow. The air-conditioning provides a welcome relief from the day’s heat and humidity, and after cataloging my latest batch of images, I drift off to the sound of the waves rolling through the Mozambique Channel.

I have never seen a red so rich and graphic as that of the dust billowing behind our SUV as we dodge potholes on the dirt road leading north to the Kirindy Forest reserve. The color of it saturates the landscape around us, infusing every leaf and limb. If not for the abundance of life everywhere, I’d be tempted to describe the scene as Martian.

A few hours into our drive, however, we break into a clearing devoid of vegetation. The land has been stripped of color, and nearly everything else. There’s nothing but charcoal and blackened stumps as far as I can see in any direction. “Slash and burn,” Herilala says somberly. “The farmers here cut and burn down everything for the zebu and for farms.” Over the next few days I’ll see the smoke from fire after fire on the horizon. Madagascar is always burning.

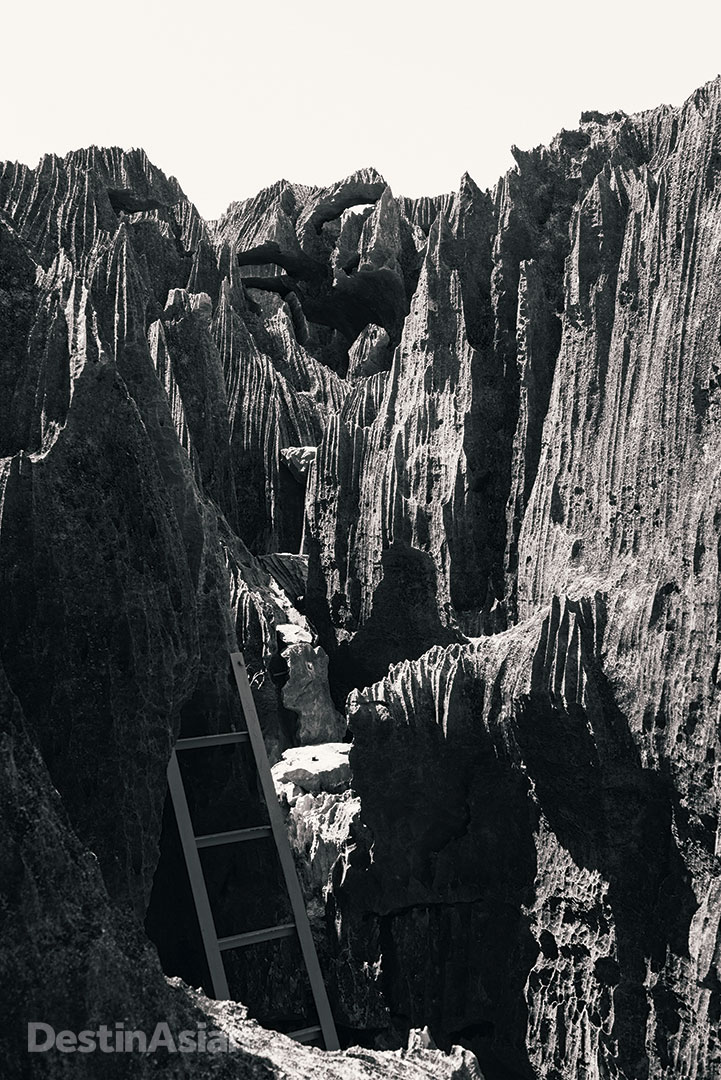

A ladder guides the way up razor-sharp limestone rocks in the karstic badlands of Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park.

The island is believed to have lost somewhere between 80 and 90 percent of its original forest since the arrival of its first settlers—seafarers from the Indonesian archipelago—in the middle of the first millennium A.D. Around 40 percent of that loss has been in the last 70 years. The exact extent of the deforestation here is hard to pin down, but few would argue that it hasn’t reached a near-catastrophic level. How the Malagasy respond to the crisis ahead of them may well determine the future of their island home.

It is mid-afternoon when we pass a large stone tablet marking the entrance to Kirindy. The reserve is mostly covered by dry, deciduous forest, and the gently falling leaves in shades of faded greens and browns give it a distinctly autumnal feel. Finally we pull into Ecolodge de Kirindy and unload our luggage into basic wooden cabins. They’re not much more than mosquito nets draped over covered mattress pads on wooden frames, but they’re a welcome sight after a day of potholed roads.

“Come, Matthew. Come this way quickly,” Herilala urges after dropping my rucksack on a spare mattress. “There is a fossa.”

Grabbing my camera, I follow him around the cluster of cabins to where a park guide is laying down within a meter of the recumbent animal. Given that fossas look something like miniature brown cougars and rank as Madagascar’s largest predator, this strikes me as unwise. But the fossa just casts a lazy glance our way before rising with a patently feline stretch and silently padding off into the underbrush.

“When they mate they are very loud,” Herilala says matter-of-factly.

We’re soon joined by a guide named George. His French is much better than his English, so I leave the translating to Herilala. George motions to us to follow him down a dirt road and onto a well-worn forest path. Dragonflies flit about as we wind our way through the light-speckled underbrush. The chirps of parrots echo in the canopy overhead, and a troop of adorable sifaka lemurs leaps between the trees in search of ripe flower buds.

“These are Verreaux’s sifaka,” Herilala says. “Kirindy is one of the few places you can find them. They always travel in a family group. We call them the dancing sifaka.”

As we watch, the primates hop lower and lower down the trees around us until they’re at eye level just a few meters away. All cotton-ball fur and long, slender limbs, one locks his piercing yellow-green eyes directly on my camera lens before vaulting to the ground and bouncing off with a springy side-shuffle. One by one the remaining sifaka dance away across the forest floor. And that’s just the opening act. Over the next hour, we’ll spot a spiny-tailed iguana, Madagascan magpie-robins, crested drongos and couas, and two narrow-striped mongooses peeking out from their burrows.

After returning to the lodge for a hearty dinner of zebu steak served with a mysterious but delicious root vegetable, we venture back along the darkened forest trail brandishing half-meter-long flashlights. At night, an entirely new crop of creatures emerges from tree hollows and leaf-covered dens—here, a red-tailed sportive lemur; there, an Oustalet’s chameleon. Our ears quickly attune to the sounds of the jungle, registering every rustle of a leaf or snap of a branch. Were it not for the beams of our flashlights, the setting would be entirely primordial.

Leaving Kirindy shortly after dawn, it’s a few hours before we hit our first major crossing at the Mania River. There’s no bridge. Instead, we wait in a line of SUVs for our turn to board a “ferry” that consists of two steel-hulled riverboats strapped together under a makeshift deck of metal grates and timber planking. When it’s time for us to board, a pair of bowed metal planks are thrown down, one for each set of wheels. They sag worryingly as our driver Faly noses the Nissan across.

The river itself is a rich ocher brown from the sediment continually kicked up by its swift-flowing waters, and it takes us almost 45 sun-blasted minutes to reach the far shore. When we do, the metal planks are thrown down again and we roll off into the dusty hamlet of Belo Tsiribihina, where we grab a quick lunch of prawns and collard greens before continuing on through the semi-arid landscape. Along the way we stop at a wood-and-thatch village or two to say hello to smiling children and take their pictures with the Polaroid camera I’ve brought with me. The photos are my gift to them—far better than candy or pocket change, and something that Herilala assures me they’ll treasure for years.

It’s not until late in the afternoon that we reach our second river crossing. Thankfully, the muddy banks of the Manambolo are narrow here. I imagine I could swim to the other side, were it not for the Nile crocodiles that Herilala says lurk in the turbid waters.

Across the river lies our final destination—Bekopaka and the UNESCO-listed Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park. That’s for tomorrow though. Right now, we’re content to follow the flood-washed road to our bungalows at Le Soleil des Tsingy, a four-year-old lodge overlooking a verdant forest canopy. Here, an enormous thatched dining and reception hall gives way to a blue-tiled infinity pool, while bungalows come decked out with net-draped four-poster beds, hand-woven textiles, and paintings by Malagasy artist Zach Edith. It’s an almost disorienting degree of luxury.

After a dinner washed down by too many bottles of Madagascar’s ubiquitous Three Horses beer, I’m not in the best shape for our four o’clock wake-up call the next morning. But the promise of seeing Tsingy de Bemaraha has me almost jumping out of bed. Tsingy, a Malagasy word that roughly translates as “where one cannot walk barefoot,” is the name given to the razor-sharp limestone pinnacles that jut out of Bemaraha’s karstic plateau, cut through by canyons and gorges shaped by millennia of erosion.

The sun is barely cresting the horizon when we arrive, strap on harness equipment, and begin a kilometers-long hiking circuit. There’s a surprising amount of endemic wildlife here, even by Madagascar standards. Some 70 to 80 percent of the creatures that call the tsingy home exist nowhere else on the island, and it doesn’t take us long to spot some—a Coquerel’s coua, Decken’s sifakas—under the cool forest canopy.

A series of planks and ladders aid our ascent up the rocks. Out of the shade, the heat is oppressive, even at this early hour: it radiates between the pockets of limestone like a living entity. I’m dripping sweat by the time we reach a high crevasse spanned by a narrow suspension bridge. More than 100 meters below lies a bed of knife-edged rocks. Mustering my courage, I carefully lock my harness and carabineer onto the guide wire and begin to cross the chasm, feeling like I’ve stepped into an Indiana Jones movie. It’s utterly exhilarating. Unclipping on the other side, I have to squeeze between two rock formations and clamber over a series of planks before reaching a lookout platform at the top. The panorama is breathtaking—a forest of stone that seems to shimmer under the hazy equatorial sun.

After climbing back down, Herilala takes us to a wooden, dirt-floored café in Bekopaka for a well-earned round of beers. The town’s mayor, a young man with a curly chinstrap beard, is there as well, sitting at a long table with a group of advisors and two rifle-wielding guards. After a few minutes he comes over to greet us and ask where I’m from.

“What do you think of our tsingy?” he inquires with a smile.

And I know just what to tell him. “I’ve never seen anything like it anywhere in the world.”

The Details

Getting There

From Southeast Asia, the best route to Madagascar is via Johannesburg, from where South African Airlink operates daily flights to Antananarivo. Morondava, the west coast’s gateway town, is a 10-hour drive from the capital for those who wish to rent a private car and driver; otherwise, it’s a one-hour flight on Air Madagascar.

Where to Stay

Lokanga Boutique Hotel

Antananarivo; 261-34/ 145-5502; doubles from US$140.

Palissandre Côte Ouest

Nosy Kely, Morondava; 261-20/955-2022; doubles from US$158.

Ecolodge de Kirindy

Kirindy Forest; 261-32/401-6589; doubles from US$40.

Le Soleil des Tsingy

Bekopaka; 261-20/222-0949; doubles from US$110.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2017 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Madagascar On The Mind”).