The buzz persists in other hangouts favored by Colombo’s elite. The courtyard of the Gallery Café, located in the old offices of legendary Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa, is filled at night with expat businessmen and aid workers. At the genteelly decrepit Galle Face Hotel, snagging a table on the patio for sundowners is nearly impossible.

Residents take palpable pride in their city’s recovery. Whenever I pass the site where Shangri-La is planning to build a 661-room hotel, my taxi or rickshaw driver points to it and proudly announces, “New Shangri-La hotel will be here.”

If there’s any question as to whom you should credit with Colombo’s—or rather, the country’s—renewal, just look around.

Photos of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who led the defeat of the Tamil Tigers, are plastered everywhere. In the photos, he is always dressed in a white kurta and sarong, a red scarf draped around his neck. A few billboards sport full-length portraits, though headshots seem the more popular choice. Sometimes the president is flashing a toothy grin, but more often than not he looks somber, gazing off to the right, slightly upward, as if his cares are not of this earth. He’s even on the 1,000-rupee note, beaming with his arms raised in triumph.

International outcry over the killing of civilians in the war’s end-game only bolstered Rajapaksa’s standing among Sinhalese voters, who see Sri Lanka as being David to the West’s—and above all, India’s—Goliath. His admirers liken him to Dutugemunu, a Sinhalese king of the second century B.C. who vanquished an Indian Tamil invader. They crow about his achievements in the way ancient rulers were lauded. “First time president, he stopped the war. Now he builds roads,” my driver, Jayathissa, tells me.

One such road is the new four-lane, 96-kilometer highway linking Colombo to Galle. A towering billboard near the entrance shows Raja-paksa striding down the expressway. Nearby, a link road is still being constructed. As we pass it, I spy a Chinese man in a hard hat directing a handful of Sri Lankan workers—Japanese and Chinese contractors were the ones who actually brought the road into existence.

It’s also completely empty, because locals are either reluctant to pay the 400-rupee toll or too loyal to the old Galle Road, a clogged, cacophonous nightmare. But that’s not stopping plans for more expressways, with Chinese firms lining up for the contracts.

Chinese travelers are also venturing to Sri Lanka’s shores. At the Avani Bentota hotel, a Bawa creation that’s been recently refurbished, Suranjit de Fonseka, the director of marketing, is showing me drawings and batik by Laki Senanayake and Ena da Silva, who were part of Bawa’s close network of artists and designers. We’re interrupted when a bus disgorges a group of Chinese tourists, who loudly chatter about their lunch prospects as they stream around us. Thankfully, a different sort of tourist frequents the historic precincts of Galle Fort. At the Galle Fort Hotel, four young women from Beijing, chicly dressed in floaty blouses and cotton scarves, pore over their iPhones, scouring blogs for suggestions as to where to have dinner that night.

Galle Fort is both unchanged and unrecognizable from my last visit. Cafés crowd Leyn Baan Street, while on Church Street, Souk 58 boutique sells pricey pillowcases and Indian pottery. “There has been more change in the last six months than in the past ten years,” says Olivia Richli, general manager of the Amangalla, once the storied Oriental Hotel. After lunch, Richli, who has the elegant bearing of a dancer, shows me around the property. Some longtimers lament the old hotel’s transformation, but I’m taken in by its cool spaces and tasteful selection of period furnishings, including porcelain water coolers and bank safes.

Parts of Galle Fort, which was protected from the 2004 tsunami by its ancient ramparts, remain impervious to its newfound status as a travel hot spot. Residents still take their morning constitutional on the Dutch-built ramparts. At the primary school near Court Square, children chant their multiplication tables. Men in white skullcaps and sarongs hurry to the mosque during the call to prayer.

Along the stretch of Lighthouse Street where I’m staying, neighbors start to greet me, preserving the small-town ambience. One evening, though, a woman with a dupatta draped modestly over her head asks me where I’m staying. I point down the road, and as I walk away, I hear her say in a low voice, “Are you interested …” I ask her to repeat herself, and she mumbles, pulling a corner of her dupatta nearly over her mouth, “Are you interested in homemade greeting cards?” I laugh, but I also feel a touch of alarm.

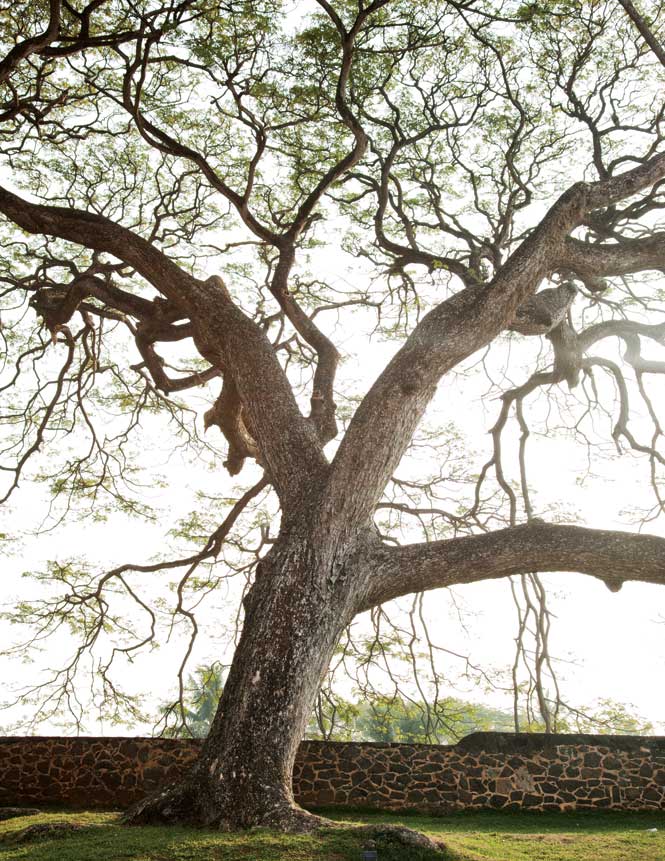

Seeking respite from the commercialization, I check into Kahanda Kanda, an eight-suite retreat deep in the jungle about a half-hour tuk-tuk drive from Galle. Owner George Cooper, an English interior designer whose great-grandfather was a rubber planter in Sri Lanka, created it as a private getaway before opening the rooms to guests in 2006. His manager, Pubuntu Udara, a gracious young man with a shaved head and mellifluous baritone, escorts me up the long flight of steps at the entrance. Inside the resort, every structure directs your gaze outwards onto sweeping vistas of the surrounding forest. A low wall shielding some of the bungalows has windows cut into it, while the open-air lounge looks out onto a nearby lake.

My bungalow is lofty and impeccably furnished, with armoires and a four-poster bed swathed in smooth white sheets. The others are filled with exquisite items from Cooper’s travels and former life in Gloucestershire: a portrait of an 18th-century ancestor, kilims, an ikat-patterned robe, and French antique block-printed textiles.

But my favorite feature of the bungalow is the wide terrace, where in the morning I watch flocks of parakeets and a troop of purple-faced leaf monkeys scamper along the treetops. Sybarites will appreciate the low-key luxury, but I suspect it’s the nature lovers who fall hard for it. At breakfast, I overhear an elderly Englishman delightedly reel off the birds he’s seen, as if reciting a poem: the green imperial pigeon, the rose-ringed parakeet, the Asian paradise flycatcher.