A luxury riverboat cruise between Luxor and Aswan takes in the lush landscapes and archeological wonders of Upper Egypt, where the crowds have thinned but the ancient magic endures

By Isabel Esterman

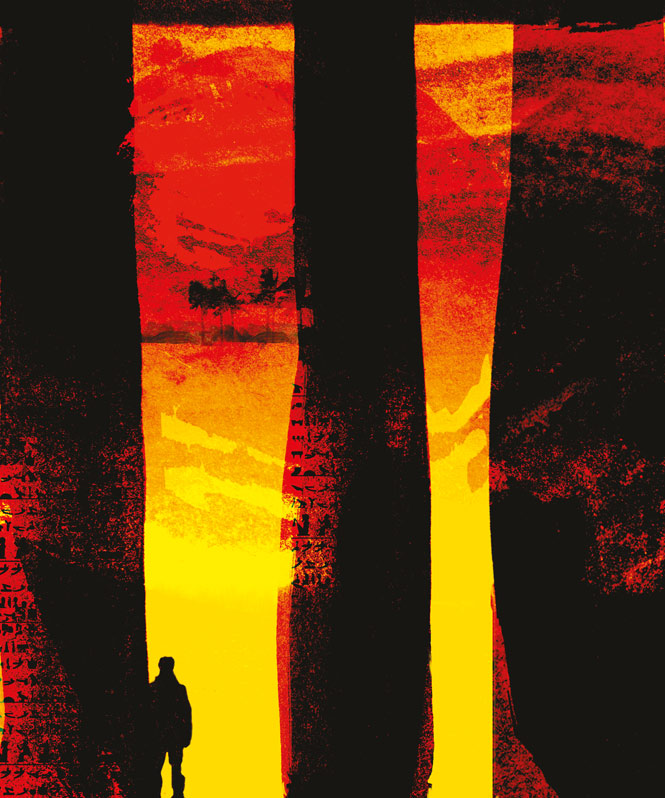

Illustrations by Simon Pemberton

As the sun dips low across the Nile and the Sahara beyond, the forest of columns around me blushes pink and orange. Lengthening shadows heighten the relief of the murals and glyphs carved in their sides.

More than 3,000 years ago, when the Karnak temple complex stood newly built above the city of Thebes, it must have been truly breathtaking. Every figure and inscription was brightly painted with precious pigments of gold, malachite, and lapis lazuli. The 134 columns of the Great Hypostyle Hall, their capitals shaped like lotus blooms and papyrus buds, supported a vaulting, tiered roof that allowed shafts of light to stream onto the gleaming alabaster floor and reflect up onto the faces of the statues that lined the chamber. The pharaoh and his priests would enter the sanctuary to commune with Amun-Ra, the god of gods, while commoners worshipped in the courtyard outside.

Standing in the great hall today, its roof long since collapsed, I can’t help thinking I prefer the temple as it is now: crumbling, evocative, silent. A thin stream of visitors trickles through the complex, but every time I leave the main walkway, I find myself alone, free to wander in solitude among the ruins, admire the symmetry of the colonnades, and search for hidden places where faint traces of the original colors have managed to cling to millennia-old plaster.

Karnak is the first pharaonic site on a weeklong cruise through Upper Egypt, and its emotional resonance catches me by surprise. Egypt is like this, I’ve learned. Over-saturated by Hollywood images of pyramids and temples, I feared I might have become jaded, and half expected these ancient monuments to be somehow underwhelming, rendered cliché by a glut of bad travel posters and movie sets.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. As with my 2008 visit to see the Sphinx, which proved no less mesmerizing for the Pizza Hut across the road, here in Karnak, I am just as transported as the Victorian travelers, imperial adventurers, and Arab chroniclers who passed this way before me. The temples are magnificent, mysterious; nothing I might have seen or read about them prepared me for the wonder of actually setting foot on these stones.

The following morning, when we cross to the Nile’s west bank and disembark for an excursion to the Valley of Kings, I’m astonished yet again. As we drive along an empty desert road into striated hills, leaving behind green fields of sugarcane, I can feel acutely the starkness and the desolation that led pharaohs of the New Kingdom to believe their remains could find eternal, uninterrupted rest in these rocky heights.

By about 1800 B.C., pyramids had gone out of style as burial sites. They were too big, too showy, and far too visible to grave robbers. In the Valley of Kings, however, pharaohs could arrange to be buried so deeply that modern archeologists, armed with electromagnetic sensors and the latest image-analysis software, have still not located the tombs of at least five major rulers who are believed to rest in the hillsides.

A pharaoh would begin work on his tomb from the moment he ascended to the throne, enlarging it and decorating it until his death. Thus, the tomb of the valley’s most celebrated occupant, the boy king Tutankhamen, is in fact one of the smallest. Tutankhamen was just 18 when he died, and his mummy, still on view within, seems almost impossibly slight. The wall paintings within his crypt are beautiful and detailed, depicting in vibrant colors scenes from the Book of the Dead. But they are just that: paintings. Ordinarily, the walls would have been plastered with gypsum, with every figure and glyph carved in meticulous detail before being painted. Skipping this step speaks of haste, or economy. Likewise, when British Egyptologist Howard Carter opened the tomb for the first time in 1922, he found the antechamber in a state of “organized chaos,” with precious objects heaped and jumbled together.

King Tut’s coffin alone was made from more than 110 kilograms of pure gold, and more than 7,000 statues, ritual objects, household items, and jewels have been catalogued. If this was the grave of a minor king, on the throne for a mere decade, it is staggering to imagine what a tomb like that of Ramses IV, cut 70 meters into the living heart of the mountain, must have contained. Or that of Ramses III, who ruled for 35 years. Stripped bare some 3,000 years ago, they are still splendid. Every inch of the walls is covered in intricate friezes from Egyptian mythology, full of gods standing in judgment, beheaded enemies, three-headed snakes, and other dangers the pharaoh would encounter on his journey to the underworld.

Occasionally, in spots where the plaster has fallen from the walls, I can make out chisel marks, a reminder that every single piece of this work—from hacking out tombs to hauling enormous sarcophagi up from the Nile—was done by hand, with nothing more sophisticated than bronze and copper hammers and chisels. Later, at the Valley of Nobles, where wealthy merchants, officials, and artisans built tombs of their own, we meet an artist named Ahmed, who, alongside his brother, carves fine replicas of the wall art within. Even with decades of practice, and the benefit of steel tools, he tells me it can take anywhere from a week to a month to replicate a design about half a meter square.

Normally, this would be the peak of the high season for tourism, with charter jets disgorging legions of travelers to enjoy the mild, sunny days and crisp nights of the Egyptian winter. On a busy day, the Valley of Kings alone can see more than 9,000 visitors.

Current events, however, have overshadowed the ancient past, and by and large, tourists are staying away. According to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism, visitor numbers in 2011 were 30 percent below those of the previous year, with just 10.2 million arrivals. Even that figure, though, seems wildly optimistic.

The past year has been historic and thrilling for Egypt, but also extraordinarily unstable. With the images that are streaming through cable networks, it’s no wonder travelers are looking elsewhere for their holidays. On television, the country looks like a war zone.

In downtown Cairo, protesters’ tents still fill the center of Tahrir Square, and concrete walls and barbed-wire checkpoints block streets around government buildings. Wander just a kilometer from here, though, and Cairo is just as beguiling as ever, a glorious, cacophonous collision of wild traffic, boisterous street vendors, men playing back-gammon and smoking shisha at sidewalk cafés, storefronts selling racy lingerie, and boys bicycling through alleys with boards piled high with bread balanced on their heads. Even in the streets leading up to Tahrir Square, the greeting a foreigner is most likely to hear is still “welcome to Egypt”—a sincere salutation, as far as I can tell, even if the ultimate goal is to sell you an overpriced souvenir.

“Tourists are not being targeted,” says Sameh Samir, a Cairo University–trained Egyptologist who serves as our guide throughout the cruise. “Not a single tourist has been injured in the revolution.” When the uprising against former strongman Hosni Mubarak began last January, it wasn’t driven by religious fundamentalism or anti-Western sentiment, but by young people longing for a better life.

“You’re Egyptian, hold your head up high,” goes one popular revolutionary chant. After three decades and countless indignities under the thumb of an autocratic regime bloated with corruption, people have tasted their own power. On an earlier visit to Cairo in July, I could see a new pride in people, especially the young. Young men zipping around central Cairo on motorcycles are no longer seen as hopeless cases; instead, they are the heroes of the revolution, frontline fighters, or the ambulance corps who shuttled injured protesters to field hospitals. Even the untidiness of graffitied streets, smashed pavement, and the burned-out husk of the former headquarters of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party is exhilarating in a country where, little more than a year ago, people could be hauled from their beds in the middle of the night for criticizing the regime.

For all the new exuberance, however, there’s still a long way to go. Elections are slowly proceeding—the largest gains in which seem to be going to Islamist parties, who were conspicuously absent from street protests—but in the meantime, with Mubarak gone, Egypt is in the hands of a military junta, whose response to ongoing protests has been heavy-handed, brutal, and often terrifying.

Desperate to stabilize a free-falling economy, the ruling generals have even less desire to disturb tourists than protesters do. Tourism is a bedrock industry, employing one in eight Egyptians. In 2010, it earned some US$12.5 billion in hard currency, dwarfing the US$5 billion brought in by the Suez Canal. “Now we would be very lucky if we make seven or eight billion,” says Sameh. “And it doesn’t just affect those who work in tourism. It’s everybody.”

But if central Cairo remains a dicey proposition for visitors, Luxor, 720 kilometers to the south, is placid. Flights and trains run on time, shops are open for business, and those who wish to bypass the outbursts of trouble in the capital can easily do so by flying directly to Luxor, or traveling by way of the Red Sea resorts. The only real noticeable difference is the lack of crowds.

“It’s a very bad situation for Egypt,” Sameh tells us. “But it’s very good for you.” Normally, some 300 boats would be cruising the Nile between Luxor and Aswan, docked three or four deep outside major embarkation points or plying the river in such numbers that it can take six hours or more to pass through the lock at Esna. Yet so many sailings have been canceled that we don’t have to wait at all. And even those vessels that retain a normal schedule—like the Oberoi Zahra, which I’m traveling on—are running with very light loads. For my journey, we’re just six passengers aboard a ship built for 10 times that many.

I feel a bit guilty, I have to admit, for benefiting from what is clearly a difficult time for the Egyptian travel industry. But it’s glorious, all the same, like having a private yacht at your disposal for a week. And what a yacht: operated since 2007 by India’s Oberoi hotel group, the Zahra is unquestionably one of the classiest cruisers on the Nile. At 72 meters long, it has plenty of room for all of the amenities one could hope for—elegant water-level restaurant, screening room, spa, lounge, and wooden sundeck complete with heated pool—with none of the kitsch associated with Nile riverboats. There’s not a scrap of Astroturf or gilded furniture on board; instead, it’s furnished throughout with parquet floors, Italian marble, earth-toned textiles, and tasteful art.

Even at full occupancy, the Oberoi Zahra retains a staff-to-passenger ratio of almost two-to-one. With just half a dozen guests on board, I can barely conceive a desire before someone is on hand to fulfill it. Fresh-squeezed orange juice while I lounge on the sundeck? Chilled mineral water? Sunscreen? I have my pick of sun loungers, any time of the day, or any armchair I wish to use in the boat’s cozy library. Before 24 hours has passed, it seems that the entire crew knows my name, my food preferences, how and when I take my espresso.

Even when we disembark, the feeling of being on an exclusive VIP tour persists. When we make a nighttime visit to the temple of the falcon-headed god Horus at Edfu, the best-preserved of Egypt’s major temples, we have the entire complex to ourselves, wandering undisturbed through the colonnaded courtyard and into the silent inner sanctuary. At Kom Ombo, a riverside complex with temples devoted to Horus and Sobek the crocodile god, the only other visitors are a gaggle of local schoolchildren, many of whom—like the dapper young man, perhaps 10 years old, dressed in a black suit with a bow tie and white dickey, who kept surreptitiously snapping photos of our group on his phone—seem more interested in us than they do in Kom Ombo’s intricate carvings of medical procedures, scalpels, bone saws, and other surprisingly modern surgical implements.

Writing in 1847, British archeologist Sir John Gardner Wilkinson advised those embarking on a trip down the Nile to prepare a vast store of goods including an iron bedstead, powder and shot, and an iron rattrap. Onboard the gleaming Zahra, though, everything has been provided. At just over 26 square meters, my cabin is compact, but as comfortable as a luxury hotel room. I have a queen-size bed with crisp white sheets, a work desk, Wi-Fi, cable TV, and a seating area with a large sliding window. Should I be immodest enough to open the curtain in the bathroom, another picture window awaits, allowing one to shower with a view.

As we wind upriver from Luxor to Aswan, it’s clear that life along the Nile is changing with the times. Satellite dishes sprout like mushrooms at a town we pass. Gone are the shadouf—the ancient counterweighted bucket-and-pole systems used to draw water from the river—replaced by the less picturesque, but also less backbreaking, diesel-powered pump. Even the old cycle of flood and subsidence, which once dumped rich silt along the Nile’s banks, ended with the construction of the High Dam in the 1960s, trading the ancient riparian rhythms for the stability of hydro-electric power.

For much of the trip, though, the views from the deck look very much as they must have hundreds, even thousands of years before. In the morning mists, the lush valley of the Nile looks almost tropical, the banks opening out into green fields of banana, date palms, and sugarcane. Birds flock along the shore: plovers, glossy ibis, herons, cormorants. Mud-brick houses cluster along the shore, many topped with conical dovecotes, and farmers ride donkeys or work alongside water buffalo to till and harvest their fields by hand.

In the starkest of contrasts, the serrated teeth of desert hills, or the silky golden dunes of the Sahara, press up against the thin emerald strip that lines the riverbanks. And beyond them lies nothing but desert—Libya to the west, the Red Sea to the east, and the gentle curve of the river into the distance.

I slide easily into a routine of slow mornings and lazy afternoons watching the scenery roll by, punctuated by visits to temples and superb meals. It’s true that these modern luxuries and climate-controlled rooms remove some of the drama, the sense of adventure that marked excursions like Wilkinson’s. But while I unwind with a Thai massage in one of the boat’s four dedicated treatment rooms, or tuck in to the third course of an exquisite meal prepared exactly to order, I hardly feel deprived—especially when I read warnings, like Harriet Mantineau’s 1846 advice to fellow women travelers that the vermin along the Nile are so aggressive that “I do not recommend a discontinuance of flannel clothing in Egypt.”

In addition to hot showers, freedom from lice, and other creature comforts, I also become more and more aware of the intellectual benefits of traveling in modern times. From the fall of the Roman Empire until the Rosetta stone was deciphered in the 1820s, hieroglyphics remained a mystery. The walls of Egypt’s ancient temples were mute and impenetrable. For the past 200 years, vast efforts have been made to decipher the inscriptions, and we now know much more about the meaning of these monuments, and the lives of the people who built them, than has been available for almost two millennia.

Furthermore, many of the temples and tombs we visit would have been far less visible to earlier generations of cruisers. Edfu temple was buried in sand until 1860, as were Luxor and Karnak. After the construction of the Aswan Low Dam in 1902 Philae temple, a jewel-like mélange of pharaonic, Roman, and Greek architecture dedicated to Isis, spent much of the year submerged by flood waters, until a massive UNESCO project relocated and reassembled some 47,000 pieces on a higher island. As recently as 1989, a cache of 26 statues was found beneath the Sun Court of the Luxor Temple. Now on display at the Luxor museum, these exquisite carvings of gods, goddesses, and pharaohs are among the finest existing examples of Egyptian statuary.

To see all of these wonders, and to be spared both the discomforts of 19th-century visits and the usual hordes of modern-day tourists, is truly a unique opportunity. Egypt, no doubt, has several long, hard years before it will be completely stable. And it will likely be longer still before it has a government that meets the aspirations of its people, or is worthy of the sacrifices made by those who laid down their lives to fight for a better society. But as I board my flight back to Cairo at the end of my trip, watching the narrow green band of the Nile disappear into the endless desert while I head from the glorious past into the uncertain future, I feel lucky to have found the perfect time to make this journey.

Seven-night cruises between Luxor and Aswan on the Oberoi Zahra start from US$6,640 per person, full board, including excursions. 9 1-11/2389-0606.