In Seoul, a resurgence of interest in Korea’s traditional tile-roofed residences is breathing new life into this rich architectural legacy—often in ways that are unexpectedly modern.

Photographs by Jun Michael Park.

Overlooking the newly built hanok of Eunpyeong from a window-side seat at 1In1Jan café.

Any notion that vernacular Korean architecture is underappreciated seems faintly ridiculous in Bukchon. On a sunny afternoon, the winding lanes of Seoul’s most famous district of hanok, or traditional wooden houses, are in danger of being overrun. Couples crowd timber doorways festooned with fading calligraphy or gleaming brass, and tour groups line up to pose against the backdrop that has inspired a million Instagram posts—a sea of delicately flared tile roofs cascading gently downhill toward the office towers of the city center.

Indeed, Bukchon Hanok Village has grown so popular that the local government deploys marshals to remind noisy tourists that despite its toy-town appearance, this is a living, breathing residential area. For the inhabitants, the patterned stone walls that hide most of these lovely homes from view may not feel nearly high enough.

Yet interest in hanok is a very recent phenomenon, among locals and tourists alike. The art and proliferation of the Korean-style house reached an apex during the Joseon Dynasty from the 14th to 19th centuries, but the tumultuous years of Japanese occupation, fratricidal war, and rapid industrial development that followed were tough ones for old buildings, hanok included. “The entire history of architecture in Korea was really cut,” says Daniel Tandler of Seoul-based architecture firm Urban Detail, which has overseen numerous hanok projects. As South Korea grew more prosperous, humble, typically single-story dwellings of wood and clay seemed less something to aspire to than humiliating reminders of a poverty-stricken past, and gleaming apartment blocks mushroomed in their place.

The outdoor hearth at Rakkojae, one of the city’s most revered hanok hotels.

So what changed? Some credit must be given to the government. In 2001, Seoul launched a regeneration program that directs funding to the protection and restoration of hanok, which are now seen as “indispensable to upholding traditional architecture and culture, and protecting the city’s identity,” says Kim Seong-chan, a public relations manager with the city’s Hanok Heritage Preservation Division. The program has saved hanok clusters in areas such as Donuimun—which once marked Seoul’s western boundary—from the wrecking ball, though, as Kim admits, the surviving houses “make a stark contrast” with the high-rise apartment complexes behind them.

Since the program began, the city has managed to maintain around 11,000 hanok and has led a broader nationwide resurgence in hanok architecture. But in addition to the besieged residents of Bukchon, there is a number of young architects, designers, and creatives who would be hesitant to call the current approach to hanok an unqualified success. Whether it be Bukchon or Jeonju Hanok Village in Korea’s southwest, there are concerns that hanok neighborhoods fetishize—and fossilize—a watered-down version of the past, ignoring the fact that hanok themselves have constantly evolved, and boast qualities that are light years ahead of their time. Rather than sticking rigorously to tradition, these people are reworking hanok for an anxious contemporary age, creating distinctive new venues and cultivating new audiences in the process. “Korean architects are just starting to go back to traditional architecture and extract more from that for modern architecture,” Tandler says. “That makes it an interesting time to be here.”

Tourists dressing the part in Seoul’s historic Bukchon Hanok Village.

Teo Yang is a case in point. Something of a rising star on the Korean (and international) design scene, he was educated in the United States and Europe, immersing himself in Western artistic traditions before returning home and realizing “there’s so much beauty to discover and explore in Korea.” Seven years ago, he moved into a handsome old hanok on the fringes of Bukchon. “It was love at first sight,” he recalls. Now his home and studio, the renovated building encapsulates the balance Yang strives to achieve in his work, with cool marble floors supporting its weathered wooden frame and a space-capsule like reading room with immaculate eggshell-white walls that opens onto a courtyard dominated by a gnarled pine. “It’s important for me to show that anybody who lives in the 21st century doesn’t have to look at hanok as an old artifact,” he says. “It’s a tradition, but it’s also a living platform that we can utilize and appreciate in the present day.”

To advocates like Yang, while beautiful, the most prominent aspects of hanok—the gently curving tile roofs, the intimate courtyards, the emphasis on natural materials—aren’t necessarily what make them so special, since variants of these are found in other East Asian architectural traditions. Rather, it’s the way hanok design seems to anticipate entirely current needs.

Inside Teo Yang’s home and studio.

The basic hanok layout includes a daecheong, or wide central hall. Facing the courtyard, it functions as a reception and living area, separated from the outside and private rooms at the rear by sliding doors of wood and hanji, a translucent paper typically made from mulberry bark that filters light into a warm, comforting glow. This allows the daecheong to be easily opened to the elements, serving as a patio and allowing cool breezes to flow through the property in the summer, while the traditional ondol underfloor heating system, which warms the house via a wood furnace (or these days, hot water pipes), keeps everyone snug during winter.

Other rooms, meanwhile, can be sealed off for privacy or contemplation, or opened to create larger space configurations. Standard furnishings, such as bedrolls, small lacquer tables, and folding screens, are relatively austere and designed to be easily dismantled or carted from place to place. The hanok is therefore modular and lends itself to modification, equally conducive to quiet study or a big dinner gathering, encouraging communion with nature and achieving much with a relatively small footprint. The perfect building, in other words, for our era of spatial and environmental constraints.

A patio at Rakkojae.

Yang has incorporated hanok features into many of his most feted projects, from cultural centers to refurbished restrooms at a highway rest stop. Even to the plush Seoul Sky Premium Lounge on the 123rd story of the Lotte World Tower, Korea’s tallest building, where patrons might be too busy taking in the cityscape below to notice how the textured walls evoke folding screens; and his revamp of Seoul’s oldest bakery, Taegeukdang, where the lofty illuminated ceilings are patterned after latticework hanok windows.

But hanok principles may find the purest expression in the flagship boutique of Yang’s Eath Library skincare venture, located a short distance from his studio in the shadow of Gyeongbok Palace. Instead of the glass and glitter of typical cosmetic shops, visitors step into a realm where the walls are clad in rich wood, moon-shaped windows admit a cozy helping of light, and goods are laid out on handcrafted shelves set against minimalist versions of the delicate screens that grace hanok rooms. Even the products themselves, which range from soaps and lotions to lifestyle goods like bags, trays, and scented candles, come in hanok-inspired packaging; bottles, for example, mimic stacks of old books. Suffused with soothing colors and herbal scents, it’s a rare venue that is as therapeutic as its treatments, as befits a brand based on traditional medicine.

Almost Home Café occupies a hanok of its own on the grounds of the Art Sonje Center.

Barely a block away, a similar approach is evident on the grounds of the Art Sonje Center, where a formerly derelict hanok has recently been refashioned into the Almost Home Café. The building’s basic openness to the elements has been enhanced with floor-to-ceiling glass panels that open onto a garden full of flowering plants and thickets of bamboo, a sanctuary from which barely a sliver of the city beyond is visible. The furnishings and gleaming counters where lightning-quick baristas dispense espressos and green-tea lattes are entirely contemporary, yet from every angle the structure presents views that are timeless—an opportunity not lost on the café’s well-heeled clientele, none of whom seem to be in any hurry to leave.

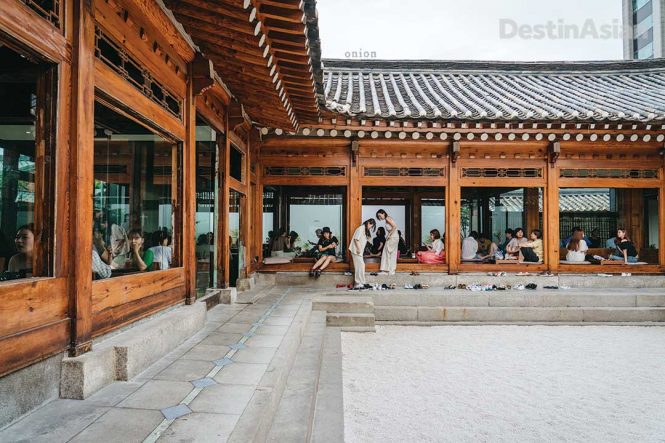

Almost Home is one of several postmodern hanok that have mushroomed in the area and attracted no shortage of social media traffic. The new Anguk branch of Café Onion, a brand rooted in Seoul’s Brooklyn-like Seongsu-dong area, brings the original outlet’s patented industrial minimalism to a sprawling old house in a quiet side street. Its vast courtyard and surprisingly spacious interiors marry soft wood and exposed concrete, with layered doorways framing shelves bursting with baked goods or leading onto successively quieter nooks and crannies. As with other hanok, the venue as a whole manages to be both complex and simple, offering openness or intimacy, immersion in nature or shelter from it, depending on which corner one chooses to claim on any given day.

Designer Teo Yang at the entrance to his Eath Library showroom.

That versatility is one reason young Koreans “are now choosing to spend their weekends in hanok instead of glitzy hotels,” says Grace Jun, who, as the owner of one of Seoul’s hottest new hanok properties, would know. Late last year in the gritty Dongdaemun area, Jun reopened an expansive century-old courtyard residence as J. Hidden House, a tranquil café and cultural space. Jun maintained many original aspects of the building, including its stout timber beams—assembled without using a single nail—and rare lattice-and-cloth windows. Heirlooms, from old furniture to an ancient pair of wooden skis, are scattered around the property, which has been in Jun’s family for generations. But it’s far too sleek and stylish to mistake for a museum, with artfully placed mirrors, globe pendant lighting fixtures, and an eight-meter tiled bar counter where fresh pastries, hand-roasted coffee, and draft beers from celebrated local brewery Hand & Malt beckon.

“I really wanted to make this a showcase of the best Korea has to offer, not only with the hanok, but also the food and beverage, and the service,” Jun explains. This is one reason the venue has become a regular staging ground for events run by organizations focused on promoting local artistic traditions, such as the Arumjigi Culture Keepers Foundation. On warm weekends, the courtyard tables are packed and the chatter is punctuated with the telltale click of cell phone cameras. “We’ve become as popular as we are through the power of social media—it’s basically hashtags,” Jun laughs. Yet she also believes hanok meet a serious need. “People are stressed, and that’s why they are looking for contemporary hanok—they want to be comforted. We were aiming for nostalgic 40- to 50-year-olds when we opened, but it’s the 20- and 30-year-olds who are coming here on dates.”

The courtyard at the Anguk branch of Café Onion.

When those dates last a little longer, residents (and visitors) can take advantage of an expanding roster of hanok hotels. Previously limited to aristocratic properties like the celebrated Rakkojae in Bukchon Hanok Village, the newer variants tend to be smaller and boast more of a boutique flair. Bonum 1957 and the more modest Beyond Stay are two prominent examples: located in the history-rich Jongno district, both guesthouses blend hanok structure with Scandinavian functionality and welcome touches like mini-terraces and marble-rich bathrooms.

And some people may graduate from overnight stays to something more permanent. After a slow start, a brand-new hanok village first planned by the Seoul government a decade ago is taking shape in the northwestern district of Eunpyeong, in the foothills of the Bukhan mountain range. Encouraged by city grants, around 50 hanok have sprung up in the area, with more under construction—the first such spate of hanok-building at scale in well over a century.

In contrast to many of the restored properties in the city center, Eunpyeong’s new hanok tend to be larger structures with more visibly modern elements, such as second stories, balconies, even garages. Yet, with their well-tended grounds and the backdrop of rocky peaks, they retain an air of harmony with nature, and the area’s relative distance from central Seoul ensures a certain level of tranquility. The district government has ambitious plans to attract more tourists. A hanok museum (in a hanok, of course) has opened alongside a number of atmospheric restaurants and teahouses, including 1In1Jan (literally, “one person, one cup”), with an eclectic neo-Mediterranean menu and a stunning raised interior perimeter where patrons dine next to windows overlooking the entire neighborhood. But despite these lures, and the abundance of soothing scenery and hiking trails nearby, the danger of Eunpyeong becoming another Bukchon seems a distant one.

Grace Jun outside J. Hidden House, a century-old hanok that she has transformed into a café and cultural space.

The neighborhood’s placid surface disguises the fact that it is in some respects at the heart of the battle over what hanok can, or should, be in the contemporary context. On the one hand, the influx of residents and steady march of construction seems welcome proof that hanok can serve modern lifestyles. On the other, few believe the district would survive without government subsidies that offset much of the cost of hanok-building. These subsidies are also controversial because they require qualifying hanok to adhere to rigid standards that critics believe essentially constrain the form. Tandler, for example, says there’s a “certain attachment” to a late-Joseon Dynasty building style that, “while probably necessary in some areas, has also held back creativity in the hanok field.”

That may be a risk in Eunpyeong, and indeed there are rumblings of discontent elsewhere about a sudden surge in cookie-cutter buildings that adopt some of the basic trappings of hanok architecture, particularly the sloping tile roofs, without the substance—what some critics have derided as imposters wearing hanok “hats.” Yet there are also encouraging examples of designers moving beyond “stereotypical thinking about hanok and thinking in a bigger context,” as Yang puts it, pushing the boundaries of the art to the extent that it may not even be immediately recognizable.

Take the Won & Won 63.5 building in Seoul’s ultra-modern Gangnam district, designed by pioneering architect and noted hanok advocate Hwang Doojin. On a cursory inspection, the slender red-brick tower looks entirely modern, even futuristic. But its porous surface, intended to reduce barriers between the building and outside, and rooftop garden, laid out like a C-shaped courtyard, are taken directly from the hanok playbook. Meanwhile, in decidedly less fashionable Sinseol-dong, a district almost completely devoted to light industry, CoRe Architects have integrated a dilapidated old hanok into a contemporary building, using a steel-and-glass framework to both support the roof and extend it vertically, so that it almost appears to be suspended in a giant aquarium. Switzerland’s new embassy in Seoul offers another striking reinterpretation of hanok design, with a low-slung central building propped up by exposed wooden beams as it curves around a spacious garden.

Projects like these are a good sign Korea’s architectural legacy is not only being reclaimed, but imbued with new vitality as architects, entrepreneurs, and consumers all find aspects of the hanok to employ, enjoy, even reinvent. Ultimately, says Yang, “if you don’t give people freedom when working with hanok, the tradition will end up like water in a pond. It’ll get stagnant.”

Address book

1In1Jan

9992-418 Jingwan-dong, Eunpyeong; 82-2/355-1111.

Almost Home Café

Art Sonje Center, 87 Yulgok-ro 3-gil, Samcheong-dong;

82-2/734-2626.

Beyond Stay

17 Donhwamun-ro 11-gil; 82-2/742-7829; doubles from US$85.

Bonum 1957

53 Bukchon-ro, Gahoe-dong; 82 2-763-1957; doubles from US$154.

Café Onion Anguk

5 Gyedong-gil; 82/70-7543-2123.

Eath Library Showroom

31 Samcheong-ro 2-gil; 82-2/723-7001.

J.Hidden House

94 Jongno 6-ga; 82-2/744-1915.

Rakkojae Seoul

Bukchon Hanok Village, 49-23 Gyedong-gil;

82-2/742-3410; doubles from US$214.

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2019 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“House Proud”).