The Cambodian city of Battambang holds a treasure trove of historic architecture. But can preservation efforts keep pace with the town’s newfound prosperity?

By Christopher R. Cox

Photographed by John McDermott

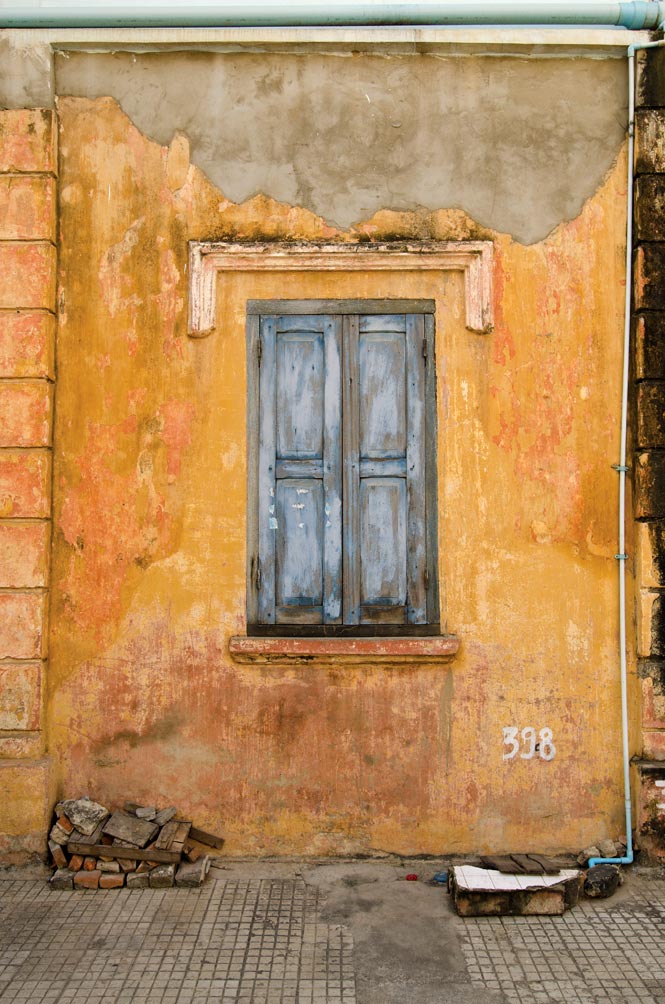

Behind the garish signs and glassed-in showrooms, it is still possible to detect the century-old elegance—graceful fluted pilasters, florid plasterwork, ocher paint jobs—displayed by a row of riverfront French-colonial shophouses in Battambang.

“This is our special asset,” says my guide, Som “Sak” Sanvasak, of the heritage buildings at the heart of Cambodia’s second-largest city. “We must preserve this for the next generation.” Sak’s urgency is informed by more than just aesthetics or nostalgia. Battambang’s historic architecture—arguably the finest assemblage of colonial-era buildings in the country—is the main draw for foreign tourists to this northwest corner of Cambodia. And Sak, who works for Deutscher Entwicklungsdienst (DED), a German NGO assisting local authorities in preserving their unique cityscape, knows that people won’t detour off the Phnom Penh– Siem Reap tourist axis just to admire the fashion boutiques or mobile-phone shops that are threatening to obscure the town’s venerable structures.

Though the drive west from Siem Reap takes only three hours, I opt to get to Battambang by water. After a 90-minute crossing of the Tonle Sap—the largest lake in Southeast Asia—the longtail boat works upstream along the serpentine course of the Sangker River and its maze of fishing weirs. The surrounding floodplain, punctuated by a Burmese-style temple called Wat Chheu Khmao (“Black Wood Pagoda”) that the Khmer Rouge once used as an observation post, gradually gives way to the rice fields and fruit orchards that have earned Battambang province a reputation as the nation’s bread basket. This being the wet season, the trip takes just over six hours, and concludes in midtown Battambang, where the Sangker flows past grassy banks.