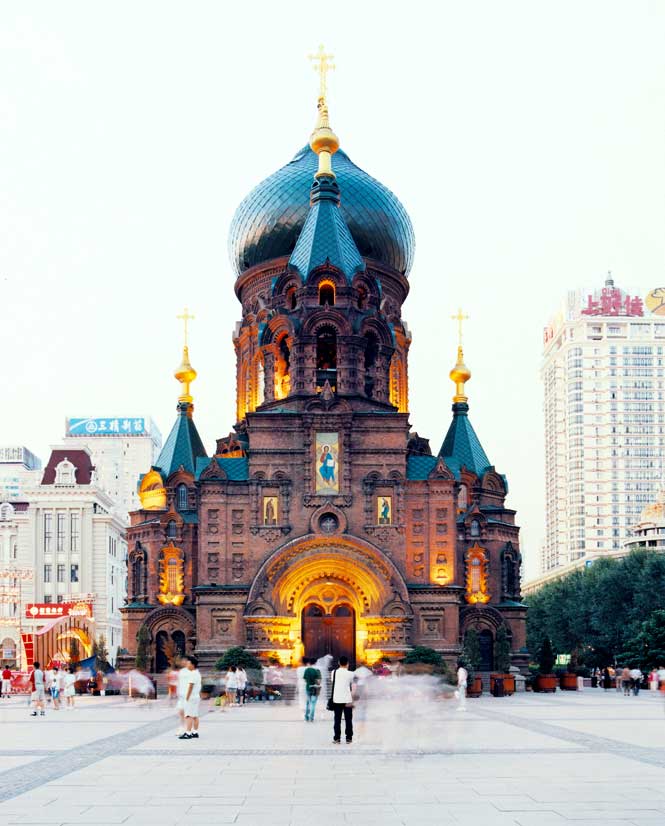

Above: From the Shangri-La hotel, Harbin’s skyline appears as a patchwork of old Russian churches, Japanese-built shophouses, and modern skyscrapers.

In China’s northeast, two cities—seaside Dalian and Russian-built Harbin—offer a tantalizing taste of the region historically known as Manchuria

By Natasha Dragun

Photographs by Andrew Rowat

“Chi, chi!” scolds Mrs. Chen, ladling another fist-sized dumpling onto my plate. “You are too thin!” It’s a phrase that I have not heard before and don’t hope to hear again. But at this dinner table everything is relative and my host, the creator of these plump, savory packages, is the ultimate advertisement for her food.

The mother of my friend and onetime Beijing colleague Cici, Mrs. Chen is almost as wide as she is high, with a bulging midriff that threatens to snap the elastic waistband of her pants. After spending nearly a decade working in the Chinese capital, Cici has moved home to the eastern port city of Dalian to look after her aging parents. And to fatten up, which she’s managing quite nicely thanks to her mother’s prowess in the kitchen.

Mrs. Chen, a bubbly sixtysomething, has been frying, boiling, sautéing, and grilling for the better part of the day. We’ve sipped steaming bowls of fish-head soup, plucked gingered scallops from their shells, wrestled with spiny crab legs, and dispatched any number of dumplings. But the feast is far from over. I pick up my chopsticks and prepare for the next round.

I didn’t have particularly high hopes for the culinary offerings in Dalian, the second-largest city in Liaoning, one of three provinces that constitute the northeastern region of Dongbei. The Middle Kingdom has its fair share of fabulous food, from pungent peppercorn-laced dishes in Sichuan to the delicate Cantonese cuisine of Guangdong and Hong Kong. The country’s culinary diversity is even chronicled in an honor roll known as the “eight great traditions”: a list of the most noteworthy regional cuisines. The food of Dongbei—an area officially known as Manchuria until 1911, when revolution brought down China’s last dynasty, the Manchu Qing—doesn’t rate a mention in this venerable catalog. The farther north you travel in China, the colder the climate, the harsher the growing conditions, and the less appetizing the food. Or so I’d been led to believe.

The rice and spice of the south disappear from the menu as you head toward the Russian border. But in their place appear corn and wheat and a surprising array of pickled and cured foods. Dongbei cuisine ranges from a seafood cornucopia in Dalian to heavy bread and smoked sausage in Harbin, the capital of Heilongjiang province. I have a long weekend, and the company of Cici and her wonderful mother, to explore it.

I arrive in Dalian from Beijing the day before our epic feast. Set on a peninsula wedged between the Yellow and Bohai seas, roughly 460 kilometers east of the Chinese capital, Dalian has emerged as one of China’s most important ports, earning it a local reputation as “the Hong Kong of the North.” It’s also a major fishing hub: from here, abalone and puffer fish are exported to Japan, salmon and sturgeon roe are crated to Russia, and cod and tilapia are frozen and boxed off to the United States. Chinese tourists descend on the city to purchase boxes of dried sea slugs and preserved sea horses, which they boil into elixirs believed to promote health and longevity.

Much of Dalian’s windswept south coast is flanked by a long expanse of forested parkland. The few buildings thin even further as we near the Chens’ apartment, which overlooks a small, pebbled beach. “Locals don’t like living here near the water because it’s humid and their clothes won’t dry,” Cici explains. Instead, the majority of Dalian’s 6.5 million residents live in blocky buildings around the sheltered port near the center of town.

A tiered counter sags under the weight of piles of pAtés and terrines and more than a dozen types of sausage. We order a smoky, sun-dried sausage and toasted tripe with pine nuts and sesame oil

I glimpse, among the towers, occasional reminders of the city’s past: pretty colonial buildings erected during decades of foreign control, beginning with the Sino-Japanese war in 1894. The Russians followed soon after, with the commencement of work on the Chinese Eastern Railway, an extension of the Trans-Siberian destined to link Vladivostok and Dalian through Harbin.

A tug-of-war between Russia and Japan saw much of Dalian destroyed. And then rebuilt. At the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, Japanese occupiers set about turning Dalian into one of the most developed port cities in the Far East. Three decades later they had established the puppet state of Manchukuo, with Puyi, China’s last Qing emperor, installed on the throne. Thousands of farmers and fishermen driven by war and poverty crossed the Bohai Sea from Shandong province to work in Manchukuo’s factories and sparsely inhabited fields.

Like many Dalian residents, Cici’s laojia, or ancestral home, is Shandong. The Chens and their fellow migrants brought to Dalian more than just their agricultural skills; they also brought the flavors of Lu cooking, widely regarded as one of the most influential culinary styles in the country. Shandong cuisine is characterized by its artful presentation and simple flavors hinting of vinegar. It’s the perfect complement to Dalian’s abundant seafood.

Four hours into our feast, Mrs. Chen is still fussing about in the kitchen, preparing another local specialty: sea worms. They’re quick-fried in baijou, a Chinese liquor distilled from sorghum, and served atop thin corn pancakes. It’s an acquired taste. Much more appetizing are the oysters, which she sautées and then combines with whisked eggs to make a delightfully rich omelet. “In November, thousands of oysters wash up onto Dalian’s beaches,” Cici’s mom says. “In the early mornings you can see people scouring the shores looking for their suppers.”

Our meal finally ends with a whole steamed bream, a Shandong inspiration. The sweet, tender flesh falls away from the bones into a light jus flecked with ginger and scallions. For the first time since she took to the stove, Mrs. Chen is still.

The next morning, I’m up early to visit Dalian’s wet market with Jek Tan, the executive chef at the city’s Shangri-La hotel. “Dongbei cuisine is misunderstood,” he tells me as we duck into the underground market. “People don’t know about it. I am really trying to put Dalian’s food onto the map.” Tan runs weekly cooking classes to teach locals and hotel guests about the intricacies of the cuisine and has developed lengthy menus to show off regional flavors and ingredients—many of which cram the endless rows of tanks that we encounter at the market. Scary- looking monkfish kiss the glass of bubbling aquariums beside huge halibut, big-lipped sea bass, and bream. Monstrous king and snow crabs are tied in bundles on the floor; and the inky-hued abalone are as big as Tan’s hand. In between tanks, stallkeepers fry up their breakfast: salted fish with corn pancakes, lobster claws with baby bamboo and tofu. “Another favorite here is octopus,” Tan says. “But they don’t slow down to take out the guts—they just roll the baby octopi onto chopsticks and eat them alive.” At another stall, a stocky fisherman boils mackerel innards in milk. “A kind of elixir,” Tan explains.

I feel compelled to buy some dried sea cucumbers, which are believed to cleanse the blood. after the previous night’s baijou-fueled feast,this sounds like something I could benefit from

On the floor above, we wander through aisles of dried seafood: piles of pinkish scallops that look like shriveled apricots; flattened squid tentacles; mountains of silvery anchovies. A tour group from Beijing is crowded around a stall selling gift boxes filled with sea horses, salamander, and sea snake. Wearing matching yellow caps and vests, they jostle over packets of abalone dried to the size of melon seeds and priced at more than US$300 a kilo. Staff from adjoining stalls rush over with similar goods and cheaper prices. Wads of yuan are slapped down, the tour guide blows her whistle, and the group moves on. I’m surprised that the dried goods are getting so much attention, what with the fabulous fresh bounty below. Tan tells me that having expensive dehydrated products in the pantry means that “you can show off at your dinner parties all year round.”