At the same time, though, Bhubaneswar retains a sleepy, small-town feel. The Mayfair Lagoon—the lovely, colonial-style hotel where I’m staying—and the low-rise Trident next door offer the only top-class accommodations, as well as the city’s modest claims to nightlife. Both are situated on vast, tree-lined properties complete with jogging trails and tennis courts. I savor starting my mornings with coffee on my private terrace, watching the school of koi and family of Brahminy ducks troll the Mayfair’s sun-dappled lagoon. Scorching hot for much of the year, Orissa is lovely in the winter.

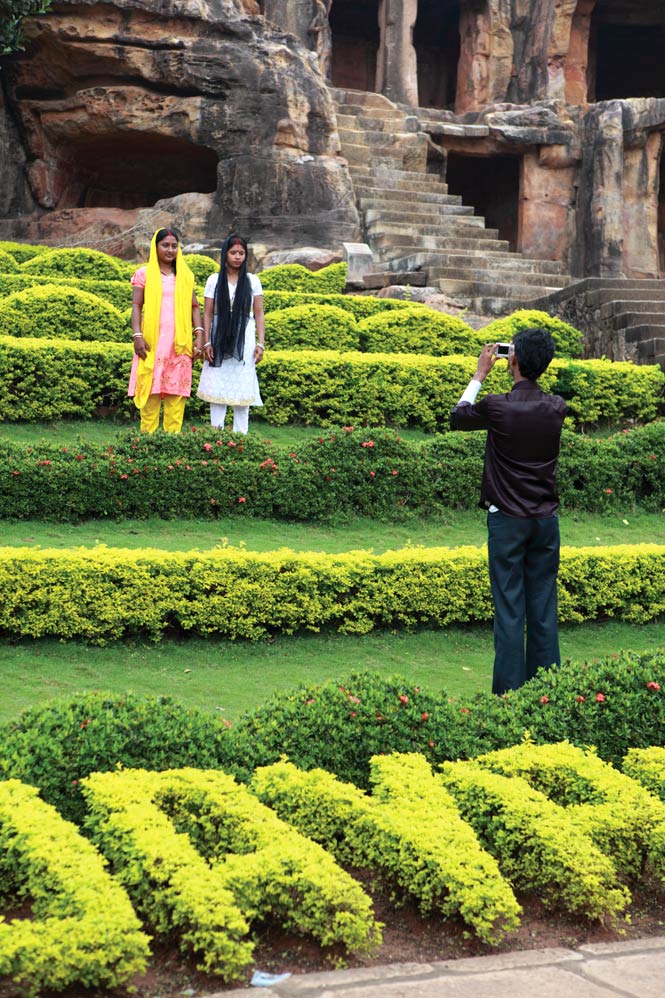

Compared with most other places I have visited in India, parts of Bhubaneswar seem practically deserted. On the morning I visit the 11th-century Rajarani Temple, the only sign of life outside the complex is a single, drowsy watchman. Inside, I encounter just two other tourists, a pair of New Yorkers speculating about some arcane aspect of Hinduism as one of them presses his palms to the gingerbread-colored sandstone walls, as if to absorb the wisdom of their great age. It’s a similar scene across town at the Museum of Tribal Arts and Artefacts, where one can wander in solitude amid display cases featuring the traditional crafts, musical instruments, and hunting implements of Orissa’s 62 indigenous tribes.

For lunch, I meet Debashis Patnaik (no relation to the chief minister) at the Lewis Road branch of his family-style restaurant chain, Dalma, which takes its name from Orissa’s signature puree of yellow lentils. A balding 50-year-old dressed in a white button-down shirt and black-framed Buddy Holly glasses, Patnaik has agreed to introduce me to Oriya cuisine. But first, he must check in on things next door, where a photographer is shooting food for a coffee-table book he has written.

“A decade ago, there was not a single dedicated Oriya cuisine restaurant anywhere,” Patnaik explains when he returns. “Not in India, not abroad, not even in Orissa. We have some exclusive dishes, but there’s no cooking school, no documentation. So many recipes were dying out.”