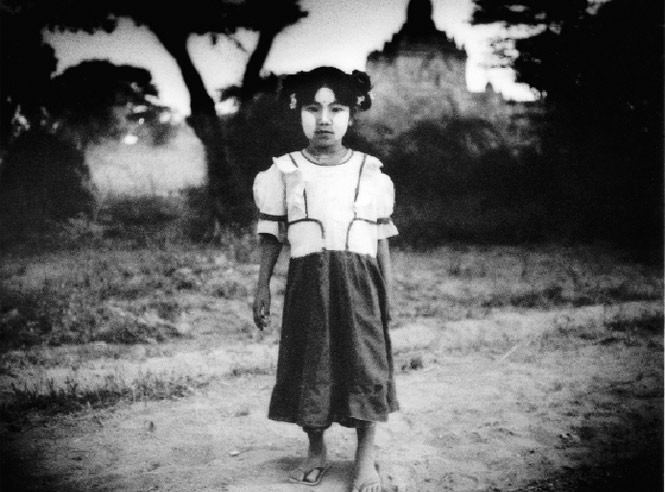

Saw Tun (again, not his real name) was fiercely intelligent and deeply ironic. He wore a camouflage cap and a traditional longyi, a fashion statement that I interpreted as his commentary on the struggle between the military and traditional cultures. He had traveled across Asia, and he viewed the decrepit splendor of Bagan as a metaphor for the wrecked state of Burmese culture. “Burmese people demand nothing,” he said. “The generals have successors in line for the next 30 years. Even when they go, the country is full of spies and informers. Whose side will they be on?”

I asked Saw Tun why he didn’t emigrate while abroad. He told us that before he left, he was forced to sign a bond stipulating that his son would forfeit his education should he not return. “My family would suffer too much.”

Did he approve of us visiting, even if some of our dollars ended up in the pockets of the generals? “You must come,” he said. “Everyone is hostage here. If you don’t come we are locked out of the world.”

It began to drizzle as we drove out of Bagan. By the time we hit Mandalay, the country’s second largest city, it was pouring. Except for the amazing Mandalay Palace, the town is a modern grid of tower blocks, rutted roads, and mud. Even the palace’s immense beauty was sullied when our guide—let’s call her Mi Mi—informed us that it was restored by chain gangs and corvée laborers, including children, as part of the nationwide beautification program that preceded Visit Myanmar Year.

We wanted out of Mandalay immediately, but Mi Mi wasn’t keen to jump through the bureaucratic hoops it would take to alter our program. After a small squabble, she suggested we check the weather before zooming off on mountain roads prone to mudslides. We told her that we had tried watching television, but the Burmese version of The Morning Show didn’t do weather—one old monk reciting prayers for four hours was the extent of the entertainment lineup. Exasperated by our insistence, Mi Mi took us to a cyber café so that we could check the forecast on Yahoo! It was located on an empty floor of an empty office building. A Christmas tree and an armed guard lent a strained surreal cheer to the entrance.

The Internet exists here, sort of. It is hideously expensive for Burmese to use. Censors screen all incoming e-mail, and outgoing e-mail is blocked—which rather defeats the purpose. Mobile phones cost about US$300 a month (a few months’ salary) and the generals control the towers. They can cut access with the flick of a switch.

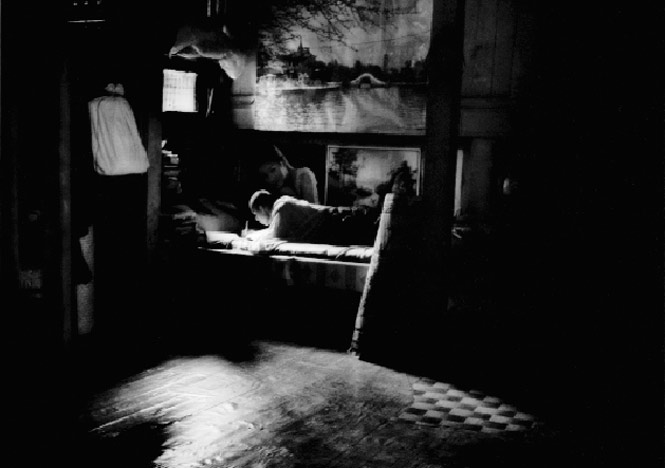

Resigned to a rainy day in Mandalay, we headed for a monastery that was out of town up a winding mountain road. We saw young monks performing their ablutions in a communal bath area; others were lying around on bedrolls, reading, sipping, or slurping bowls of instant noodles. It didn’t feel like a forbidding holy place, more like a relaxed college dorm where everyone happened to have a shaved head. By tradition, Burmese men are expected to don maroon robes and take up temporary monastic residence at two points in life, once during childhood and once after age 20. It’s not compulsory, but it’s highly encouraged as it conveys stature upon the family. These days, it’s also the only sure way to get an education and a proper meal.

Buddhism is a much more passive religion than Hinduism or Christianity—it doesn’t seek converts. It also teaches that life is suffering. Some say this encourages fatalism and submissiveness in adherents; I’d say starvation and isolation are the more likely culprits in Myanmar. I came to love the alms parade that occurred each dawn when young monks across the country go from house to house, bowls in hand, collecting food. In Buddhism, feeding monks brings good fortune, and I was taken with the idea of a society that is rewarded for literally nourishing its young.

But something shifted last September. Apparently, food shortages forced villagers to forgo their alms, which in turn caused them great distress for shirking their religious obligations. The poverty the monks witnessed encouraged them to take to the streets, where they crouched in front of guns, chanting metta (loving kindness) and singing the national anthem. The Tatmadaw tear-gassed, defrocked, jailed, and tortured some of them. They raided monasteries, smashing statues and stealing donation boxes. The entire clergy remains depressed.

I didn’t realize at the time how deeply the Burmese monks had etched themselves into my consciousness. Since my return home, every time I see a photo of those shorn men in maroon robes, the cobwebby smell of cooking and old teak and the throaty chanting come flooding back. The fact is, I’m more connected to their aspirations because of what I witnessed on the ground. And ultimately that’s why Aung San Suu Kyi and I will never see eye to eye on the tourism debate. If I hadn’t visited, the ongoing struggle of the Burmese would just be more noise to me, just another international news story. The Dalai Lama, for his part, has never supported a tourism boycott of Tibet, saying he considers it tantamount to turning one’s back on a culture. If the Burmese I met—people like Than and Saw Tun and Mi Mi—didn’t have the chance to meet foreign visitors and to tell them their story, they would surely feel even more cut off from the world than they currently do.

Reunited with Than back in Yangon, we asked him to drive by the home of “the Lady,” as Aung San Suu Kyi is referred to by her followers. She has been under house arrest in a lakeside villa for 12 of the last 18 years. I wanted to pay homage, as she had been a silent presence on our journey, a mother figure forcing us to examine the ethical consequences of our visit at every turn.

Impossible, Than told us. The road to her house has been barricaded since 2003, when her detention was resumed following a bloody attack on her motorcade by government-sponsored thugs.

Aung San Suu Kyi isn’t your run-of-the-mill dissident—she’s more like a living saint. She is the daughter of a national hero, U Aung San, who negotiated Burma’s independence from Britain before he was assassinated in 1947. Today, most Burmese carry a small photo of her in their wallets or taped to the back of their furniture. Deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, she was elected president in 1990 by an overwhelming majority, but the regime ignored the election and slapped her under house arrest. Since then her husband, British Tibetologist Michael Aris, has died, her two sons have grown up abroad without her, and many members of her political party have been jailed.

The Lady, now 63, has never fulminated against the military rulers, perhaps because she is too much of a realist. Over the years, she has spoken to visiting journalists about South Africa’s peaceful transition to democracy, indicating that she’d be willing to work with the generals to free her people. Out of the blue, on November 9, 2007, Aung San Suu Kyi met with the junta and later pronounced that the doors to reconciliation were open. The regime, in turn, has stopped describing her as “irrelevant,” but then extended her house arrest for another year in May, amid the chaos following the cyclone. That move probably didn’t come us a surprise to most Burmese. After 46 years of disappointment, they have learned that optimism shouldn’t be indulged too often.

Limited and measured: that’s the Burmese approach to hope. And never was that clearer than on our final day with Than. As we headed to the airport he pointed out a sign, written in English, that hung above the road. “To a new and developed country,” it proclaimed.

“Burmese like that sign,” Than said. “Because to us, the only way to a new and developed country is on a plane.”

THE DETAILS:

Myanmar

Before You Go

For those planning a trip to Myanmar, research the political issues and status of post-Cyclone Nargis reconstruction on useful Web sites such as The Burma Campaign (burmacampaign.org.uk) and The Burma Project (soros.org/ burma).

If You Go

Consider staying at independently operated hotels to make sure your money goes to the private entrepreneurs who run them. The Strand (92 Strand Rd., Yangon; 95-1/243-377; ghmhotels.com; doubles from US$280) in Yangon is a good option, owned and operated by Singaporeans. The French-operated Pansea Yangon (35 Taw Win Rd., Yangon; 95-1/229-860; pansea.com; doubles from US$160) is also worth considering. In northern Kachin state, Malikha Lodge (95-1/652-809; malikhalodge.com; from US$1,350 per person for three nights, all-inclusive) is privately owned by a husband-and- wife team who also organize cultural day trips and other activities, including hot-air ballooning over the temples of Bagan (easternsafaris.com). The iconic Road to Mandalay (orient-express.com) voyage along the Irrawaddyy River ceased operations after Cyclone Nargis, however it is set to resume its cruises come summer 2009.

Originally appeared in the August/September 2008 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“On the Road to Mandalay”)