Borneo’s Batang Ai region is a haven for wild orangutans, thanks to an age-old tribal taboo that has protected the apes for as long as anyone can remember.

Getting to Nanga Sumpa involves a 90-minute longboat ride upriver from Batang Ai Lake. All photos by Mark Eveleigh.

“The orangutan was trying to tell us something,” says Andah anak Lembang, shaking his head mournfully. “We should have seen his visit as a message and been prepared.”

I am sitting with a group of Iban hunters on the communal veranda of Nanga Sumpa, a riverside longhouse on the edge of Batang Ai National Park in the eastern Malaysian state of Sarawak. As Andah recounts the story, his wife absentmindedly rubs the dark scar of a burn she got three years ago while rescuing a grandchild from the fire that swept through the longhouse’s 33 family rooms shortly after that rare but ominous visit by an orangutan.

“The fire killed one old woman and destroyed virtually everything we owned,” Andah says. “It was so hot it even melted the metal of our forefathers’ ancient gongs.”

There are those who say that the people of Nanga Sumpa were foolish not to heed the orangutan’s warning.

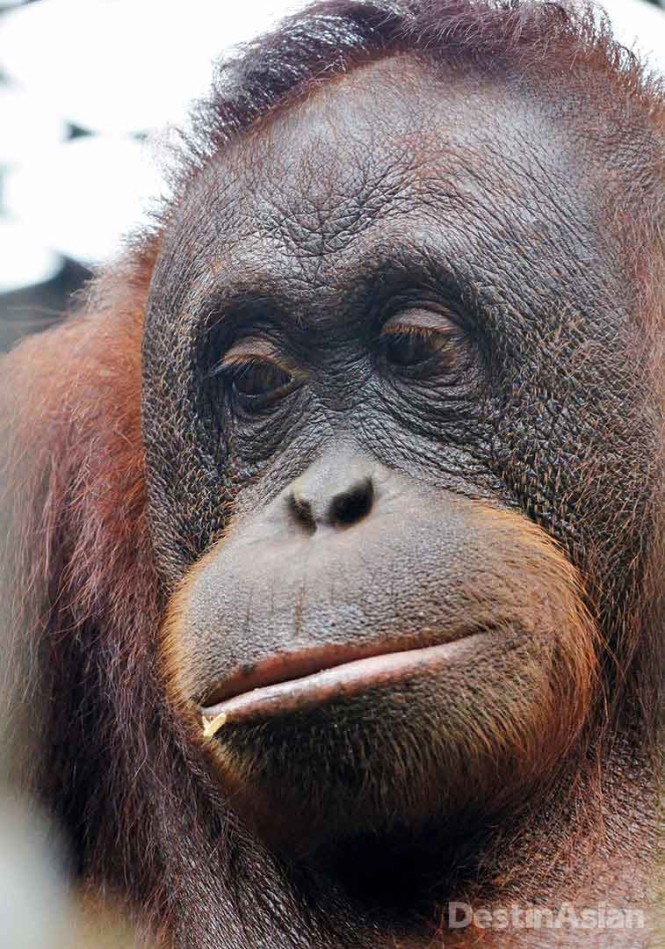

Close encounters with wild orangutans are not recommended, but residents of Matang Wildlife Centre near Kuching, the Sarawak state capital, are considerably more approachable.

Omen animals play a big part in Iban life even today. If you’re entering the jungle and a trogon bird calls from the right, you can be reassured that all is well, they tell you. But if a kingfisher flies across your path from the left, you’d better beware of some unforeseen danger. A hornbill visit or the call of a flying lemur while you’re setting up camp is a sign that you might be in the line of falling trees. And to the Iban’s headhunting ancestors, an owl, with its loosely swiveling head, was a warning that their own heads might be loosened by the end of the day.

But no animal in the forests of Batang Ai is as portentous as the orangutan, which has been protected by a tribal taboo since the Iban migrated to this area two centuries ago. With few exceptions, logging companies have learned not to tangle with the longhouse communities here and few poachers want to chance their luck against a veritable army of Iban “orangutan conservationists.” This perhaps explains why most of Sarawak’s surviving wild orangutan population is found in Batang Ai and the neighboring wildlife sanctuary of Lanjak-Entimau, which together encompass about 2,000 square kilometers. According to Sarawak Forestry, the area is home to between 2,000 and 2,500 orangutans.

Although the Iban of Batang Ai are enthusiastic hunters (subsistence hunting is legal in the reserve), there are very few instances of them killing an orangutan. The apes are, after all, many things to the Iban: ghosts, messengers, saviors, friends. Occasionally, they’re even considered to be family.

“Some Iban claim their grandfathers were reincarnated as orangutans,” Bayang anak Penguang, a guide with local outfitter Borneo Adventure, tells me the next morning as we begin our trek into the forests beyond Nanga Sumpa. “Sure, we’ll try to frighten an orangutan away if it comes too close to our home, because that is always a bad omen. But the Iban have a sort of friendship with them too, and there are many accounts of orangutans helping people in the jungle.”

As we traverse a chain of valleys, wading across streams and stopping frequently to pluck leeches from our legs, Bayang shares tales about orangutans that have shown lost villagers the way home or—in one legendary instance—acted as midwife to a woman giving birth in the forest. Such stories are at odds with those I’ve heard across the border in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), where the apes have a more ferocious reputation, as evinced by the famous yarn about an orangutan that attacked and ate an entire Dutch colonial militia. Apparently, it spat out only the rifles.

The wooden sheath of an Iban parang (machete), held together by natural twine and not-so-traditional cable ties.

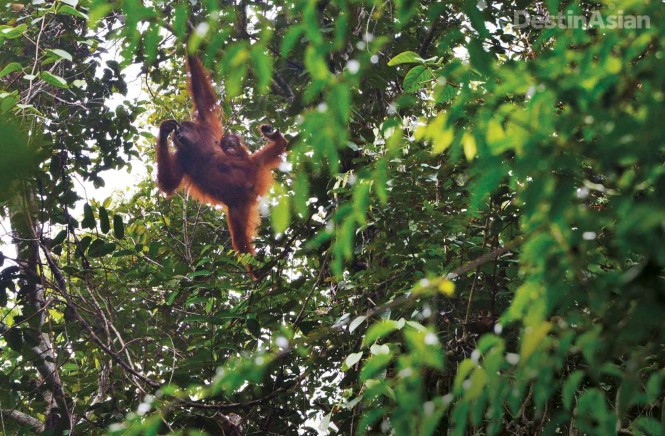

We’re just an hour beyond Nanga Sumpa when we spot our first wild orangutans: a mother with a baby clinging tightly to her side. Watching them traverse the forest canopy, it’s easy to appreciate the Ibans’ attitude toward these most charismatic of apes. Orangutans have a facial expressiveness that often seems to surpass even that of humans, and their obvious strength demands respect. We catch the snorting sound of another orangutan farther up the valley, so Bayang goes to check it out. “Never let an orangutan get into the trees above you,” he warns me before leaving. “They’re strong enough to throw branches as thick as your leg.” Eyeing the protective mother nervously, I imagine she could quite easily break off my own leg and throw that at me.

Asia’s great red ape once ranged from Java to southern China but today is found only on Borneo and Sumatra, with each island home to a distinct species. The World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that a century ago there were close to a quarter-million orangutans. Today, due largely to habitat loss and poaching for the exotic pet market, there are only 104,700 Bornean orangutans and 14,613 Sumatran orangutans left in the wild.

In Batang Ai, however, the outlook for this endangered ape species seems favorable. During my five days in the area, Bayang would help me to spot eight orangutans. The 40 minutes I spent alone in the rain forest watching the mother and baby slowly retreat out of range, however, was one of the most intense experiences I’ve had in 20 years as a wildlife journalist.

By the time we reach the Mawang River three hours later, our three porters—Jimbun, Lian, and Jalang—have already cleared the vegetation that had grown around Borneo Adventure’s basic jungle camp in the weeks since the last visitors were here. Jalang, their leader, is said to be one of the few young Iban who still knows how to live off the jungle’s bounty: on the way to the camp he had netted six fish and a river turtle. Within minutes of our arrival he butchers the turtle and stuffs its meat into a segment of giant bamboo plugged at each end with fragrant leaves. Then he props this in the fire to cook, like some sort of jungle casserole. Though Bayang assures me the turtle is a common species that Ibans are legally allowed to harvest, I still feel a twinge of guilt when I dig into the poor reptile.

The Iban are tireless hunters who will usually eat almost anything. But, just as orangutans are protected by taboo, so too are several other animals considered to be off the menu. “I never knew anyone who would ever eat macan [leopard] or buaya [crocodile],” Jalang tells me. “If you eat those animals, it is possible that they can come back and eat you!”

Bayang’s campfire tale that night is similarly outlandish. He tells us of a time that he and Andah anak Lembang of Nanga Sumpa came across some terrifying tracks in a valley not far from where we’re sitting. “The footprints were like human but at least twice as long,” he whispers. “And 10 feet above was a trail of snapped branches. “We’re sure it was an orangutan that had turned itself into a giant ghost.”

It’s about then I decide that Batang Ai, with its mix of untamed wilderness and rich cultural heritage, surely qualifies as one of the most fascinating areas in all of Borneo. This comes with the added thrill of knowing that sustainable, low-impact wilderness tourism of the kind pioneered by Borneo Adventure helps to sustain a traditional culture that in turn is affording protection to a very endangered species.

As the Iban say, maybe the orangutans do have a message to tell us after all.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2017 print issue of DestinAsian magazine (“Seeing Red in Sarawak”).